About the 2025–2026 Competition

The Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court Competition final arguments—part of the Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison Moot Court Program—are the culmination of a three-round elimination competition in appellate advocacy. This year, 66 students entered the competition. In the qualifying round, held during the fall semester, students briefed one of two issues on behalf of either the appellant or the appellee and presented their positions in oral arguments before panels composed of alumni practitioners and professors.

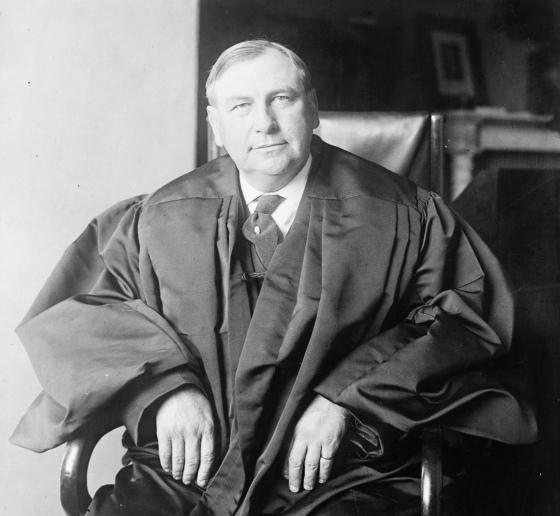

This year’s event marks the 100th anniversary of the Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court final oral arguments. Originally started at Columbia Law School in 1925 by the Story Inn, a chapter of the legal fraternity Phi Delta Phi, the competition is named in honor of Harlan Fiske Stone 1898, who was a member of the Story Inn while a student at the Law School. Stone became dean of Columbia Law School in 1910. He served in that capacity until 1924, when President Calvin Coolidge appointed him attorney general of the United States. He was named to the Supreme Court of the United States the following year and was elevated to chief justice in 1941.

The 2025-2026 Competition schedule is as follows:

Stone Competition Info Session: September 30, 2025

Problem Released: October 3, 2025

Competition Registration Deadline: October 8, 2025

Briefs Deadline: October 27, 2025

Oral Arguments - Qualifying Rounds: November 17-20, 2025

Oral Arguments - Semi-Finals: February 23-26, 2026

Oral Argument - Final Round: April 6, 2026

For more information about this year’s competition, see the Student Directors’ Blog (to be updated soon).

The 2025-2026 Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court Competition problem will be released on October 3, 2025.

The 2025-2026 Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court Competition problem will be released on or around October 3, 2025.