Remembering Two Legends in Law

A Tribute to Justices Benjamin N. Cardozo and Charles Evans Hughes, Two of the Most Influential and Accomplished Individuals Ever to Study at Columbia Law School

New York, September 12, 2013—This past summer marked the 75th and 65th anniversaries of the deaths of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo and Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. Cardozo and Hughes are two of the most highly respected and influential individuals ever to study at Columbia Law School. In this touching essay first published in the email newsletter the “Jackson List,” legal scholar John Q. Barrett examines the impact Cardozo and Hughes had on the lives of generations of lawyers and the law.

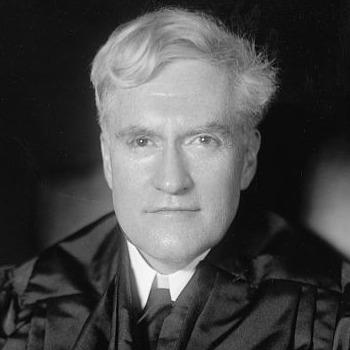

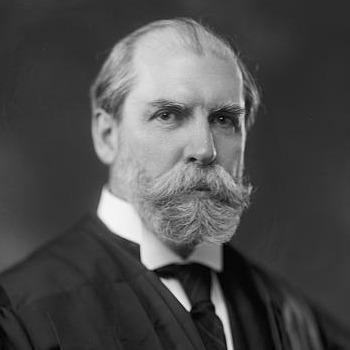

Associate Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo | Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes |

(Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Farewell to the Chief Justice (1948)

John Q. Barrett*

On Monday, December 19, 1938, the Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States began their public session with ceremonial, sad proceedings. Their colleague Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo had died the previous summer. On that December afternoon, the Court still was eight members—President Franklin Roosevelt had not nominated anyone to fill the vacancy. Indeed, only seven Justices were present for that final Court session of the calendar year—Justice James C. McReynolds was absent.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes recognized the Attorney General of the United States, Homer S. Cummings. He reported that the Supreme Court Bar had held Cardozo memorial proceedings the previous month, spoke of the Justice’s life and judicial service, expressed sorrow at his passing and presented to the Court the memorial resolutions that the Bar had adopted.1

Chief Justice Hughes, speaking both for the Court and very personally, responded at some length. His closing words reflect the deep emotion and sincerity of the love and loss that he described:

[Justice Cardozo’s] gentleness and self-restraint, his ineffable charm, combined with his alertness and mental strength, made him a unique personality. With us who had the privilege of daily association there will ever abide the precious memory not only of the work of a great jurist but of companionship with a beautiful spirit, an extraordinary combination of grace and power.2

Following the Court session, the Solicitor General of the United States—himself a Cardozo protégé and friend of twenty years—wrote a longhand letter and had a Department of Justice driver deliver it:

My dear Mr. Chief Justice:

Your tribute to Mr. Justice Cardozo was inspiring and majestic—worthy in every way to take its place in the greatest work of him in whose praise it was spoken.

The impulse to write these words is too strong to be resisted even though they do feeble justice to the impression they made on me.

Sincerely yours,

Robert H. Jackson3

Chief Justice Hughes, on the following day, dictated and sent this reply:

My dear Mr. Solicitor General:

Your generous words on my remarks of yesterday touch me deeply. I knew Cardozo from his boyhood.- I first met him at Long Branch[, New Jersey,] in [summer] 1884 when I [age 22] was tutoring a law student and he [Cardozo, age 14] was still in knickerbockers, and I cannot tell you how greatly I valued his friendship and the opportunity of working with him. I could not express all that I felt.

With kind regards, I am,

Very sincerely yours,

/s/ Charles E. Hughes4

* * *

Charles Evans Hughes lived an extraordinary life. Born in upstate New York in 1862, he became a graduate of Brown University and then Columbia Law School, and then a New York lawyer and, concurrently, a law professor. In 1905 and 1906, he became prominent as counsel to two investigative commissions of the New York State legislature. In 1906 he was elected Governor of New York and in 1908 he was reelected. In 1910, he was appointed an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U.S. In 1916, after the Republican Party nominated him as its presidential candidate, he resigned from the Court; that fall, he was defeated by President Woodrow Wilson in one of the closest elections in U.S. history. In 1921, after some years back in private law practice, Hughes was appointed Secretary of State. In 1926, he was appointed a Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. In 1930, he was appointed Chief Justice of the United States. His unprecedented second period of Supreme Court service lasted until he, age 79 and in diminished health, retired into senior judicial status.

Chief Justice Hughes in retirement was mostly a private person devoted to family. In December 1945, he became a widower after fifty-seven years of marriage. In April 1946, he made his final public appearance at the funeral of his successor, Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone.

In summer 1948, Chief Justice Hughes’s health began to fail. He traveled that August to Cape Cod, where he had spent prior summers with his children and grandchildren, in the hope of recovering. On the evening of August 27th, he died, at age eighty-six, in his cottage at the Wianno Club in Osterville, Massachusetts.5

On August 31, 1948, 1,500 people attended Chief Justice Hughes’s funeral at Riverside Church in upper Manhattan.6 At his Hughes family’s request, the service was brief, simple and interdenominational. The mourners included eight Supreme Court justices: Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson; Associate Justices Stanley Reed, Hugo L. Black, Felix Frankfurter, Robert H. Jackson, Wiley Rutledge and Harold H. Burton; and retired Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts.

* * *

Justice Jackson wrote, near the end of his life, that “the two greatest personalities of [his] time were Franklin D. Roosevelt and Charles Evans Hughes.”7 A decade earlier, while Hughes was still living, Jackson wrote this fuller explanation:

Purely apart from their abilities or attainments, merely as personalities, Chief Justice Hughes and the President outshone every other presence. They were quite different, but when they were together, as I saw them several times …, one saw two magnificent but very different types. The Chief Justice had an external severity that contrasted with the President’s external urbanity. But Hughes was one of the kindest men, and no person who saw him preside over the Supreme Court will ever have any other standard of perfection in a presiding officer. He was firm and prompt, dignified and kindly. He rarely interrupted counsel but gave them every opportunity to discuss their cases as long as they stuck to the point. He tolerated no personalities or wanderings from the issue, and he could sum up in two or three questions a whole lawsuit. He never used his position on the bench to embarrass counsel or to heckle them, and if counsel were frightened or timid or incompetent, he often went out of his way to make sure that their position was fully brought out. He was a model of dignity.8

On August 31, 1948, the remains of Charles Evans Hughes were buried in a family plot in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. His gravestone displays only his name and the dates of his birth and his death. This matches the style of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo’s

gravestone in Beth Olom Cemetery in Queens.

Copyright © 2013 by John Q. Barrett. All rights reserved. To join the “Jackson List,” which keeps recipient identities and email addresses confidential, send a “subscribe” note to [email protected].

# # #

* Professor of Law, St. John’s University School of Law, New York City, and Elizabeth S. Lenna Fellow, Robert H. Jackson Center, Jamestown, New York (www.roberthjackson.org). I emailed an earlier version of this essay to the Jackson List on August 31, 2013.

For an archive of selected Jackson List posts, many of which have document images attached, visit www.stjohns.edu/academics/graduate/law/faculty/profiles/Barrett/JacksonList.sju.

To subscribe to the Jackson List, which does not display recipient identities or distribute their email addresses, send “subscribe” to [email protected].

1See 305 U.S. xiv-xxii.

2See id. at xxviii.

3 Letter from Robert H. Jackson to Charles Evans Hughes, Dec. 19, 1938 (retyped copy), in Robert H. Jackson Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C., Box 81, Folder 6.

4 Letter from Charles E. Hughes to Robert H. Jackson, Dec. 20, 1938, in id.

5See John H. Fenton, Justice Hughes Dead at 86; Served the State and Nation, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 28, 1948, at 1, 6.

6See Final Tribute Paid Charles E. Hughes, N.Y. TIMES, Sept. 1, 1948, at 48. The service occurred one block from another Republican’s monumental tomb. See www.nps.gov/gegr/index.htm (the General Grant National Memorial).

7 ROBERT H. JACKSON, THAT MAN: AN INSIDER’S PORTRAIT OF FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT 155 (2003) (John Q. Barrett, ed.).

8Id. at