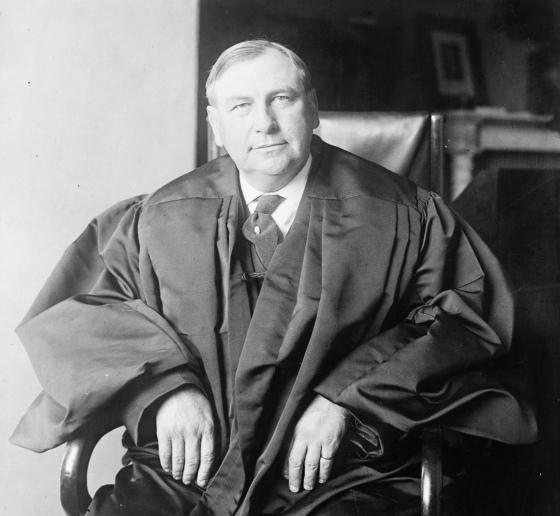

2024 Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court Finals Tackle Medical Marijuana and Collegiate Athletics

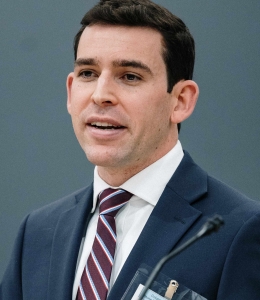

On March 21, Matt Winesett ’24 won the prize for top oralist, and Christopher Morillo ’24 was recognized for best final round brief.

Four Columbia Law School students argued complicated questions involving medical marijuana and the relationship between NCAA student athletes and their universities in the 99th annual Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court competition finals on March 21.

The fictional case was written by student co-directors Sam Gordon ’24 and Julia Konstantinovsky ’24, who both participated in last year’s competition. (Gordon was a semifinalist, and Konstantinovsky was a finalist.)

In the final arguments, Jamie Herring LAW ’24, BUS ’24 and Matt Winesett ’24 argued on behalf of the fictional Woodward University, while Dakota Fenn ’24 and Christopher Morillo ’24 represented the imaginary plaintiff, Alexander P. Brown, who was kicked off the Woodward NCAA Division I men’s basketball team after informing his coach that he had a prescription for medical marijuana to treat chronic migraines. Brown’s argument was based on a Nevada law that says employers must make reasonable accommodations for employees’ medical marijuana use; the university argued Brown was not its employee and that the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA)—which prohibits marijuana use—preempts Nevada’s law.

The students delivered their arguments before a panel of distinguished judges: Judges Raymond J. Lohier Jr. and Richard J. Sullivan of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit and Judge Arun Subramanian ’04 of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Herring started things off, arguing that Brown was not an employee of the university. But he faced pushback from the judges, including Lohier, who said—in light of, among other things, new NCAA rules that allow athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL)—that collegiate athletics are “awash in money.”

Nevertheless, Herring said, decades of precedent explicitly hold that student athletes are not employees.

“The most fundamental pillar of employment law, as stated by the Supreme Court, is whether [someone] expects to be compensated for their work,” Herring said at one point. “Mr. Brown did not expect compensation from Woodward.”

Arguing for Brown, Fenn said his client—a scholarship recipient—expected multiple forms of compensation from the university. Sullivan tried to poke holes in that argument, however, pointing out that universities would have to distinguish between scholarship athletes (who would be employees) and walk-on athletes (who would not).

“That may be what the economic realities test demands,” Fenn acknowledged.

Arguing the issue of preemption for the university, Winesett said the case was clear-cut: “Here we have a Nevada law running fully perpendicular to federal law,” he said.

When the judges pointed out that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and Congress seem to have no appetite for enforcing the CSA against those who use medical marijuana—or even nonmedical marijuana—Winesett replied, “If Congress really no longer cared about this, they should change the law.”

On behalf of Brown, Morillo also faced tough questioning, with Lohier pointing out that marijuana is still a Schedule I drug under the CSA. Morillo countered that for several years, Congress has included appropriations riders that prohibit the DOJ from using funds to disrupt states’ medical marijuana laws.

To hold that the CSA preempts Nevada’s law requiring reasonable accommodation for medical marijuana would be “throwing a wrench” into those efforts, Morillo said.

After more than an hour of arguments, the judges left the room to deliberate. When they returned, they delivered the results: Winesett was awarded the Lawrence S. Greenbaum Prize for best oral presentation, and Morillo won best final round brief.

The judges praised each of the finalists.

“You were all terrific,” Lohier said. “It was a privilege and an honor to listen to you. You’re way ahead of the game—I can tell you that.”

Subramanian said the judges were proud of the finalists and all the students in the room.

“You are the next generation of lawyers who are going to make an impact in our world for the good, and we need you,” he said.

The judges also commented on the complexity of the student-written case.

“It was a fascinating problem,” Sullivan said. “I wish we had more time. These arguments really merited it.”

Gordon and Konstantinovsky said they came up with the idea for the case based in part on a case pending before the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit, a split between state supreme courts in cases involving medical cannabis and the federal Controlled Substances Act, and an ESPN segment on NIL issues.

Both co-directors said the most relevant experience was their own time in the competition last year.

“I wanted to make sure we designed a problem that was lively and topical and that had compelling legal arguments on both sides,” Konstantinovsky said.

As a competitor, Gordon said, “You get to see just how much effort the students put into crafting their arguments and therefore how much depth and nuance the issue needs to have.”

The three-round Harlan Fiske Stone Moot Court competition began in the fall, with 16 students advancing to the semifinals in February. After the competition, Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, thanked the judges, the students, and everyone who helped put the program together, who include Director of Legal Writing and Moot Court Programs Sophia Bernhardt and the moot court board. In addition to Gordon and Konstantinovsky, this year’s board included Executive Director Haley Klein ’24, Foundation Moot Court Director Ingrid Cherry ’24, Managing Directors Eveline Liu ’24 and Justin Norris ’24, and Specialized Moot Court Director Karsyn Archambeau ’24.

Morillo said, “Arguing in front of the judges was definitely the pinnacle of my time at Columbia Law School, and I am very thankful for the opportunity.”

Of winning best brief, he added, “I love brief writing, so it’s nice to know I’m not bad at it.”

Greenbaum Prize winner Winesett said he was “incredibly honored” by the award, “especially given the strength of all the finalists.”

The competition “was nerve-wracking, challenging, but ultimately very fun,” he said, “and hopefully a preview of my eventual career as a litigator.”