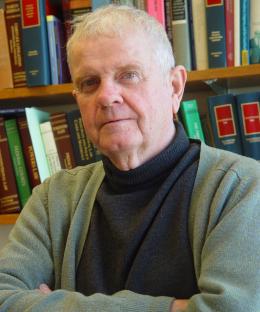

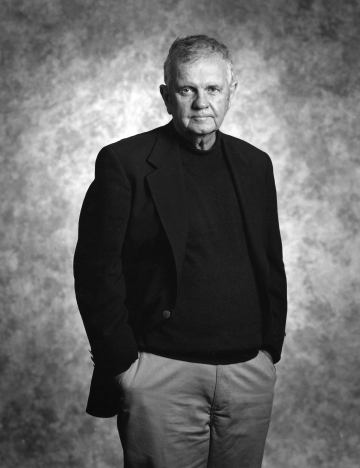

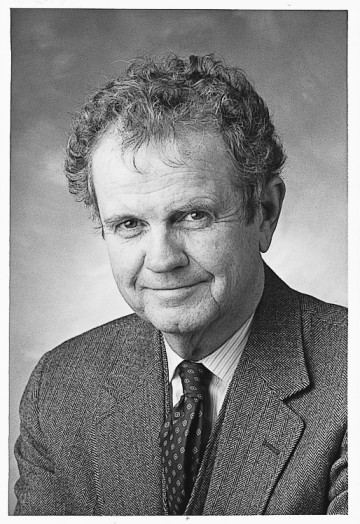

Professor Henry P. Monaghan, the pathbreaking scholar of the U.S. Constitution and federal courts who was an influential teacher and mentor to generations of legal academics, died on January 1. He was 90.

Over his 40 years at Columbia Law School, Monaghan came to be regarded as the unofficial dean of the public law faculty. “Henry was a singular force—as a scholar, a teacher, and a mentor,” said Daniel Abebe, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law. “His scholarship was deeply analytical and influential, and his views were often sought after by leading scholars and judges alike.”

Gillian Metzger ’96, Harlan Fiske Stone Professor of Constitutional Law (the endowed professorship Monaghan held for many years and which he urged be given to her even before he retired in 2024), knew him for three decades as his student, mentee, and colleague. “Henry is one of the lions of the federal courts,” Metzger said in 2017. “His exceptional analytic powers have illuminated—and as frequently reshaped—too many complex puzzles in the field for anyone to count.”

Monaghan’s views were grounded in the principle of judicial restraint, which led him to defend the Supreme Court’s decisions in Bush v. Gore and Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, but they also guided him in his successful defense of a Boston production of the musical Hair against obscenity charges and his thought leadership in support of the Affordable Care Act. In 2010, he defended the Citizens United decision, which allowed unlimited corporate and union spending in candidate elections, as “far from a radical departure from existing precedent.” And in 2012, he wrote that the individual health mandate of President Barack Obama’s signature legislative achievement, the Affordable Care Act, “surely passes constitutional muster under settled judicial principles.”

Throughout his career, Monaghan emphasized respect for precedent and the roles of the legislative and executive branches in governing. Although he wrote that he had “considerable sympathy” for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s originalist views on constitutional interpretation, Monaghan ultimately concluded that strict originalist readings of the country’s founding document could not stand. In one of his most cited articles, “Stare Decisis and Constitutional Adjudication,” he noted that Brown v. Board of Education would not have been possible under a purely originalist approach.

“Brown’s departure from the original understanding is not only defensible, but was probably the Supreme Court’s only legitimate response to the nation’s escalating moral and social turmoil,” he wrote.

Monaghan lauded Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 for her approach to originalism. “Justice Ginsburg’s position—historically constrained evolution—is an attractive one,” Monaghan wrote in a Columbia Law Review piece celebrating Ginsburg’s 10th year on the Supreme Court. “In any event, I believe that it will prove to be the only possible version of originalism as time goes on.”

A Path of His Own

Monaghan was born in Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1934. His father, also named Henry, was a stationary fireman for local paper companies. The younger Monaghan earned an associate’s degree from Holyoke Junior College in 1953 before transferring to the University of Massachusetts, where he was a member of the International Relations Club and received a B.A. in government in 1955. He attended Yale Law School, where he earned an LL.B. in 1958, and Harvard Law School, where he earned an LL.M. in 1960. He then clerked for Judge Morris Ames Soper on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit and practiced briefly in Boston at Foley, Hoag and Eliot (now Foley Hoag) before entering academia.

Monaghan spent nearly 20 years on the faculties of Boston University School of Law and Cornell Law School before coming to Columbia as a visiting professor in 1982; he joined the faculty as a tenured professor in July 1983. In 1987, he was named the Harlan Fiske Stone Professor of Law, the same title held by one of his professional idols, Columbia Law School Professor Herbert Wechsler ’31, whom Monaghan called “a legal giant.”

Monaghan never hesitated to speak out in support of his views, no matter the controversy. In 1986, he argued in an article co-written with Columbia Law School Professor Vincent Blasi that the First Amendment did not protect promotional cigarette advertising, and he testified before the Senate in 1986 in support of a ban on print advertising for tobacco products. The following year, he testified before the Senate in support of President Ronald Reagan’s nomination of controversial conservative jurist Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, which the Senate eventually rejected.

A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Monaghan was frequently honored for his thought leadership. In 2015, three of his seminal works—“Marbury and the Administrative State,” “The Protective Power of the President,” and “Stare Decisis and Constitutional Adjudication”—were celebrated by Villanova University School of Law, which honored him at the 10th Annual John F. Scarpa Conference on Law, Politics and Culture. And, in 2017, he was selected as an inaugural recipient of the Daniel J. Meltzer Award for excellence in legal education by the Federal Courts Section of the Association of American Law Schools.

A Cherished Columbian

Monaghan was an exceptionally generous colleague, and Columbia Law faculty members said he always made time to read and provide feedback—sometimes in fountain pen—on their in-progress papers, articles, and books. He received the Columbia University Faculty Mentoring Award in 2024 for his extraordinary commitment to helping tenure-track and mid-career faculty grow as scholars and teachers. “I have spent a lot of time on the work of my colleagues, and I’ve never regretted a moment of it,” he said at the time.

During her deanship, Gillian Lester, Alphonse Fletcher Jr. Professor of Law and Dean Emerita, described Monaghan as a “wise counselor” and hailed his “indefatigable generosity” as a mentor to students, academic fellows, and junior faculty. “Professor Monaghan had an eye for noticing and stewarding top academic talent,” said Lester. “He often invited students to help contribute to his academic articles, using these research and writing opportunities as a way to guide them toward prestigious clerkships with federal judges or future teaching careers; a letter of recommendation from him carried special weight.”

Metzger said he not only fostered her career but also helped her develop her voice as a writer. “Reading and commenting on colleagues’ papers is something most academics do, but Henry’s interventions went way beyond that,” said Metzger. “He would help me figure out which paper ideas were worth developing, talk through analytic challenges, and suggest sources to explore for support. I felt as though I had the great Professor Monaghan as a research assistant.”

His close friend and longtime colleague John C. Coffee Jr., Adolf A. Berle Professor of Law, described Monaghan as sui generis. “Henry Monaghan had exceptionally high standards, which no one (including himself) could ever fully meet,” said Coffee. “But despite his insistence on perfection, no one on this faculty spent more time mentoring students, reading their drafts, correcting their grammar and spelling, and discussing their theories and their possible reach. Students might have been nervous presenting their ideas to the Great Man, but he gave them his wholehearted attention, and they knew that they had received the in-depth wisdom of one of the best minds in the country.

“Henry disdained social media and the internet and focused individually on the students who came to him. They in turn received a form of intense personalized education that dates back to Socrates. We may never see his like again in our time.”

Thomas P. Schmidt, associate professor of law, said Monaghan “pervasively influenced” his thinking on the law and legal education. “He has been an especially generous mentor since the moment I joined Columbia Law School as an academic fellow [in 2020],” said Schmidt. “He routinely set aside several hours to discuss draft articles that I was working on, and they always benefited from his input and guidance.”

In the classroom, Monaghan encouraged students to think big. “Professor Monaghan rewards ‘deep’ contemplation of the issues we raise in this class,” wrote a student in their course evaluation of Advanced Constitutional Law: Separation of Powers. A student who took his Conflict of Laws course in spring 2024 wrote, “HPM is a legend and a genius. It’s very rare to have a professor who is so unbelievably intelligent, accomplished, a giant in their field, but also so invested in and accessible to students.”

Monaghan was passionate about ensuring that the Law School was a dynamic intellectual community. He created and for decades led a public law workshop series in which faculty interacted and engaged on complex legal issues over the summer. He was an affiliated faculty of the Law School’s Center for Constitutional Governance, a nonpartisan legal and policy organization devoted to the study of constitutional structure and authority that Metzger founded and helped launch.

Columbia Law School recognized Monaghan’s contributions to the community on several occasions. In 2009, the Law School hosted a symposium in his honor called “The View From the Curmudgeon’s Lair” (a reference to Monaghan’s office in Jerome L. Greene Hall). In 2010, he received the Medal for Excellence, the Law School’s most prestigious award, which is given to alumni or faculty who exemplify the qualities of character, intellect, and social and professional responsibility that the Law School seeks to instill in its students.

Monaghan was visibly moved when he accepted the medal at the annual Winter Luncheon. “I love the school,” he said. “I go to the office every day, and I have always loved that experience.”

He is survived by his wife, Nancy Hengen, and a son, Brendan Monaghan.