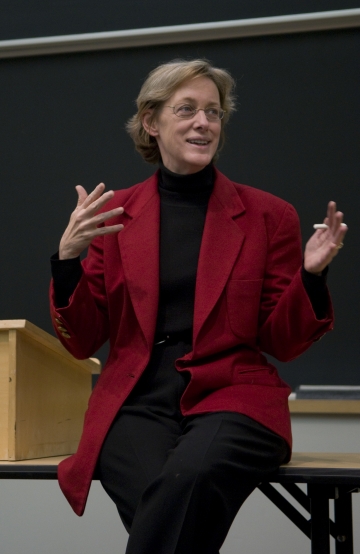

Professor Debra Livingston Invested as Chief Judge for the 2nd Circuit

A federal judge since 2007 and a dedicated member of the Columbia Law School faculty, Livingston is the first woman to lead the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit.

When Debra A. Livingston, Paul J. Kellner Professor of Law, was confirmed by the Senate 91–0 to a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit in 2007, she elected to remain an active member of the Columbia Law School faculty. “I love teaching. I love my relationship with students,” says Livingston, who has taught at Columbia Law School since 1994.

Livingston made judicial history on September 1, 2020, when she was invested as the first female chief judge of the 2nd Circuit, succeeding Judge Robert Katzmann when he concluded his seven-year term. “I have no doubt she will be a distinguished chief judge and make great contributions to the 2nd Circuit,” says Katzmann. “She is very careful, very meticulous. She is highly regarded for her opinions. . . . She is collegial. Collegiality is very important to the functioning of a court. And maintaining collegiality is a prime responsibility of a chief judge.”

As for cracking the circuit’s glass ceiling, Livingston is candid: “It’s somewhat of an accident that I’m the first woman to be chief judge because it’s something that falls upon you simply by virtue of the day you were appointed and your age,” she says. “If Sonia Sotomayor had not become a justice of the Supreme Court, I think she would have been the first woman to be chief judge of the 2nd Circuit.” (Incidentally, when Sotomayor was on the 2nd Circuit, she created and co-taught Columbia Law School’s Federal Appellate Court Externship, which is now co-taught by 2nd Circuit Senior Judge and Lecturer in Law Robert D. Sack ’63.) “

Keeping Perspective in a New Era

The duties of a chief judge have a profound impact on the way the court operates. “The chief responsibility is making it possible for a very talented group of judges to do their jobs more easily without unnecessary distractions,” says Livingston. Leading the court during a pandemic, however, has introduced new concerns. “I’ve spent a good amount of time thinking about Zoom connections and whether all my judges have the right laptops. It sounds mundane, but it’s vitally important to the administration of justice.” Livingston must continually monitor the court’s emergency protocols put in place by Katzmann, which allowed the 2nd Circuit to move seamlessly to telephonic arguments in March. “We didn’t have to adjourn a single sitting day to keep up with our dispositions,” says Livingston. “We’re working very hard to keep up with our cases and giving people the resolution that they are seeking.”

“I have no doubt she will be a distinguished chief judge and make great contributions to the 2nd Circuit.”

—Judge Robert Katzmann

Livingston says the classroom provides her with a refreshing perspective that she does not find at the courthouse. In spring 2020, she co-taught Appellate Advocacy (with her 2nd Circuit colleague Professor Gerard E. Lynch ’75) and will teach Criminal Investigations in spring 2021. “They talk about academia as an ivory tower, but being an appellate judge may be an even more remote tower,” she says. “You are appropriately cut off from members of the bar in many ways, so being challenged by students in a way that appellate judges may not be challenged every day for the decisions they reach is healthy.”

A Path of One’s Own

After graduating from Princeton University, Livingston attended Harvard Law School—where she served as an editor of the Harvard Law Review—and considered several career paths. She took a year off between her 2L and 3L years to work in Thailand for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, advocating for durable legal solutions for displaced Cambodians. She flirted with the idea of entering a Ph.D. program in anthropology after receiving her J.D., but instead took a clerkship with Judge J. Edward Lumbard on the 2nd Circuit. Livingston then worked briefly at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison before serving as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York from 1986 to 1991, including one year as deputy chief of appeals in the criminal division. After her government service, Livingston returned to Paul, Weiss for a year as an associate.

“I was drawn to academia because of my general love of university communities, the exploration of meaning and truth, my love of scientific inquiry.”

—Debra A. Livingston

Livingston launched her academic career in 1992 at the University of Michigan Law School, and two years later she joined the Columbia Law School faculty. “I was drawn to academia because of my general love of university communities, the exploration of meaning and truth, my love of scientific inquiry,” she says. “The ideal of the university is a wonderful thing for our society, our culture.”

As a full-time professor at the Law School, Livingston has taught criminal law, criminal procedure, policing, and evidence among other courses. After 9/11, she developed and co-taught a class called National Security, Law Enforcement, and Terrorism with Harold S. Egar ’67, Julius Silver Professor Emeritus of Law, Science, and Technology. Livingston also was a commissioner on New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board from 1994 to 2003 and, in 2010, she won the Law School’s Lawrence A. Wien Prize for Social Responsibility, awarded to lawyers for outstanding contributions to the public good. And she served as vice dean of the Law School from 2006 to 2007.

She believes academicians benefit from time spent as hands-on lawyers. “I sometimes worry that we’ve made it difficult for young teachers to have a career path like mine, to have the experience of practice before making the shift to academia,” she says.

The Best of Both Worlds

Livingston’s academic and judicial roles are inextricably entwined. “They are both scholarly exercises, but you start from a different place,” says Livingston, who is a co-author of all five editions of the casebook Comprehensive Criminal Procedure since it was first published in 2001. “The academic looks at the world and can reimagine the field in which he or she is thinking and writing from the bottom up and offer grand theories. But the responsibility of judges is to look at the case before them and consider what implications might it have for other cases. I have to ask, ‘Was it properly decided, even if it’s not a decision I would have made?’ We spend a lot of time in conference talking about standard of review. These questions are vitally important for a judge.”

The increasing partisanship surrounding the appointment and confirmation of federal judges and the way the media and legal critics put political or ideological labels on court decisions distresses her. “Those labels are not generally accurate to the internal debates that go on in the court,” she says. “The judges on my court are great judges, and they believe in the rule of law. They go the extra mile to try and do the right thing and understand what the right thing is. They are not politicians. I would not put that label on any one of them.”