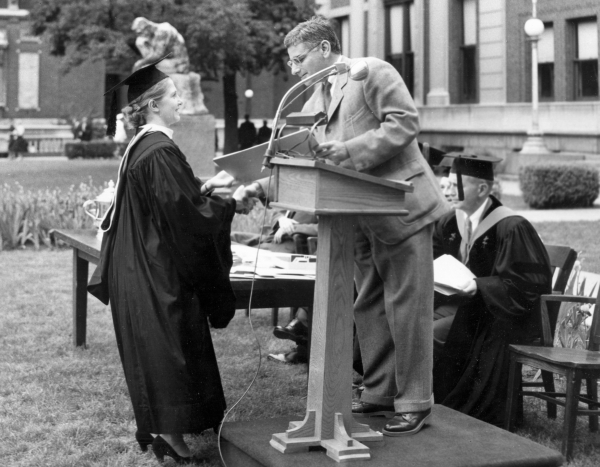

In Memoriam: Dean Emerita Barbara A. Black ’55

The distinguished legal historian and first woman to serve as dean of Columbia Law School dies at 92.

Barbara Aronstein Black ’55, a legal historian who became the first woman to serve as dean of Columbia Law School and solidified its reputation as the nation’s preeminent corporate law program while recruiting top gender and race scholars, died on January 20, 2026. She was 92.

In 1986, just two years after joining the Columbia Law faculty as George Welwood Murray Professor of Legal History, Black made history and headlines when she was appointed the Law School’s 10th dean—the first woman dean at any Ivy League law school.

“It is impossible for me to characterize the depth of Barbara Black’s impact on, and affection for, Columbia Law School. She was a singular figure in our history, someone who truly accelerated the transformation of this institution and left an indelible legacy,” said Daniel Abebe, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law. “Barbara advanced curricular reform and recruited several renowned corporate law scholars to the Law School faculty. Barbara retired from teaching in 2008 but continued to remain active both at Columbia Law School and in the legal academy writ large.”

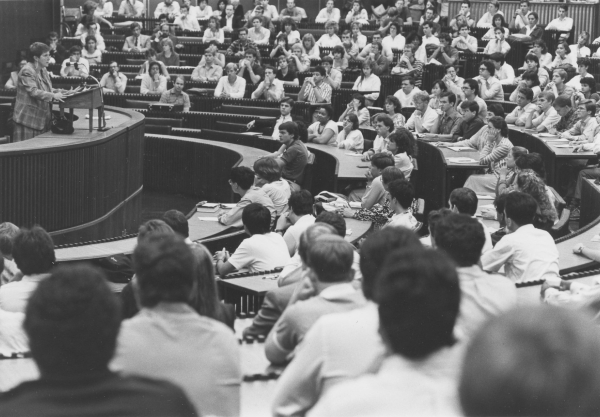

During her five-year tenure, Black oversaw an array of initiatives—the Law School launched its first Foundation Curriculum for 1Ls and increased the presence of women on the faculty and within the student body. “People credit me with bringing ... feminist-theory types here, and I will take some credit because I worked very, very hard on it,” Black recalled in Changing Lives: Pioneering New York Women Attorneys, a 2012 documentary film produced by the New York City Bar Association. Black was instrumental in recruiting both Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law, and Patricia J. Williams, James L. Dohr Professor of Law Emerita.

“Barbara paved the way for women in the profession at a time when she had very few female peers,” said Gillian Lester, Alphonse Fletcher Jr. Professor of Law and Dean Emerita and the second woman to lead the Law School. “She was a fixture of the Columbia community for decades, and I will always remember how she welcomed me with her gentle guidance, wisdom, and irrepressible wit. I will continue to be reminded of her presence and impact as I pass by her portrait in Jerome L. Greene Hall.”

New Horizons

Black was born in Brooklyn in 1933. She attended public schools before enrolling at Brooklyn College at the age of 16. She planned to attend Brooklyn Law School as her father and brothers had, but one of her professors recommended Columbia Law School, and Black changed her mind.

The decision to attend Columbia Law influenced her personal life and professional ambitions. It was there “that I suddenly woke to the fact that serious intellectual endeavor was right for me, was what I wanted to do, was what I felt myself capable of doing,” she said as part of a series of oral history interviews with the American Bar Association in 2006. She also met her future husband, constitutional law scholar Charles L. Black Jr., at Columbia Law School, where he was teaching at the time.

Black, who served as an editor of the Columbia Law Review and was one of a small cohort of women in her graduating class, discussed the complexities of being a female law student in the 1950s in a 2002 Columbia Law Review article. “One looks for expressions of dissatisfaction with the insensitivities and insults, or for complaints about the pathetic numbers of women students, the nonexistence of women faculty. It is only when we turn to … the 1960s and, especially, 1970s, that we find a different story,” she wrote. “If, dear reader, you inquire ‘Why not in the 1950s?,’ I can only say, unsatisfactorily I know, that the matter is endlessly complex. … The truth is that the presence of a handful of women students at the school was not going to make so much as a dent in the essential maleness of the law school culture, or disturb the web of assumption that underlay the belief system, such as traditional assumptions about sex roles.”

After earning an LL.B., Black remained at Columbia as an associate in law, a position generally seen as a precursor to a professorship. There were three others in her class of associates—all men. “We happened to be talking to the dean … and he said to us, ‘You know … if you want to go into law teaching, you can certainly consider this a very good first step on the ladder—at least, you three can,’” Black remembered in Changing Lives. “The fact that it was such a kind of throwaway line tells you how totally this is the way it was.”

Black left the academic world the next year to focus on raising her three children and caring for her mother, and she moved with her husband to New Haven, Connecticut, where he had begun teaching at Yale Law School.

Back to School

In 1965, Black began a graduate program in history at Yale University on a part-time basis and taught a few undergraduate history courses. In December 1975, she earned a Ph.D., and in July 1976, she became an assistant professor of history at Yale.

That same year, Black published “The Constitution of Empire: The Case for the Colonists” in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, to acclaim from the legal academy. Soon after, she received competing offers: a tenure-track position at the University of Chicago Law School and an associate professor position at Yale Law School. She accepted the invitation from Yale in 1979 so as not to uproot her family. “My mother was living with us. … We had a wonderful set up in the very large house we lived in. Everything was as good as it could be,” she recounted in her oral history.

In the spring of 1984, Yale Law School offered Black an appointment as a full-time professor with tenure. Within a week, she was invited by Columbia Law (where she was spending a semester as a visiting professor) to join the faculty as George Welwood Murray Professor of Legal History. “When I finally had to make the decision, I think the answer really was New York. As I said, I was a New Yorker; I never wanted to leave this place,” she recalled in the oral history. Her husband fully supported the move. “At this point, I did feel pretty strongly that now it was my turn. … This one was going to be for me,” Black said.

Ascending to the Deanship

Two years later, she was offered the deanship by then-Columbia University President Michael I. Sovern, a fellow member of the Law School’s Class of 1955, who described her as “an outstanding intellectual leader” and “one of our most popular teachers and most respected scholars.” She succeeded Benno C. Schmidt Jr., who left Columbia Law to become president of Yale University. She was surprised by the offer. “I just started to roar with laughter. … I finally got a hold of myself and apologized profusely because that was a really terrible way to greet this incredible compliment, this stunning honor,” she said in her oral history.

Her appointment as dean was national news and was later a clue on Jeopardy. Black also understood the position came with a downside. “I knew exactly what would happen if I took the deanship,” she said. “My scholarship would go right out the window, and of course it did.”

Nonetheless, Black felt compelled to take the position for three reasons, as she described in the oral history: self-fulfillment; the message her appointment would send to other women struggling to succeed in the male-dominated legal academy; and a sense of responsibility to her colleagues, who had suggested her for the job.

Black said she inherited many ongoing projects as dean, including curricular reform. She bolstered the corporate law faculty with the hiring of prominent corporate and securities law experts Jeffrey N. Gordon, Richard Paul Richman Professor of Law, and Bernard S. Black (no relation), as well as law and economics expert Victor P. Goldberg, Jerome L. Greene Professor Emeritus of Transactional Law. Renowned economist Richard R. Nelson of Columbia University began teaching courses at the Law School during that time, and Black invited numerous distinguished visiting scholars in the field of corporate law, including Ronald J. Gilson, who subsequently joined the faculty.

She also took initiative on several administrative matters, including enhancements to the Law School’s maternity leave policy and the introduction of a part-time program for entering students who were also mothers.

“Would this have happened without a woman in the deanship?” Black asked in the oral history. “Yes, it would have. Did it happen sooner because there was a woman [in] the deanship? Yes, I think so.”

During her tenure, Black also served twice as president of the American Society for Legal History and for several years as a member of the New York State Ethics Commission. After her time as dean ended in 1991, Black remained engaged in the life of the Law School and in current affairs. In October 2020, Black was an amicus on a brief filed by the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School on behalf of legal historians in consolidated cases against chocolate companies for their role in aiding and abetting child slavery in West Africa.

Throughout her career, Black received numerous honors and awards, including honorary degrees from Brooklyn College, New York Law School, Smith College, and Georgetown University Law Center. In January 2015, she was honored as the Distinguished Columbian in Teaching.

Black often referred to her career path as “circuitous” and advised young people not to panic should their best-laid plans not come to immediate fruition. “Don’t be discouraged when you find that the process of self-discovery takes a long, long time,” she told Brooklyn College graduates during a commencement speech in 1988. “Don’t even be surprised if at 50 you are still wondering what you are going to be when you grow up.”

“I’d like my legacy to have to do with a love of learning,” she said in Changing Lives. “It is true we train people as well to be professionals, but the job of the school is to educate. I think of myself as an educator, and if I can be thought of that way, that’s all I want.”

Black was preceded in death by her husband, Charles. She is survived by two sons, Gavin and David, and a daughter, Robin.