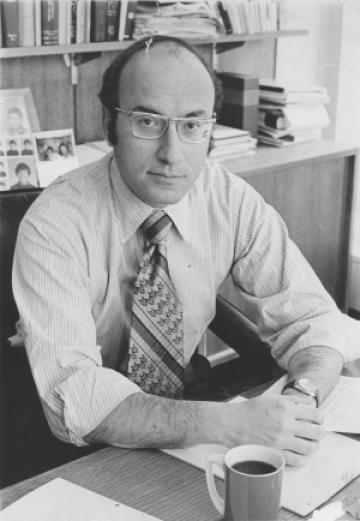

In Memoriam: Michael Ira Sovern ’55

Michael I. Sovern ’55, renowned mediator, eighth dean of Columbia Law School, and former president of Columbia University, dies at 88.

Michael Ira Sovern ’55, the eighth dean of Columbia Law School, who helped resolve some of New York City’s most divisive labor disputes, guided Columbia University through the vitriolic anti-war protests of the late 1960s, and later served as the university’s 17th president, died Monday, January 20, 2020. He was 88.

In 1960, at the age of 28, Sovern became the youngest full professor in the modern history of Columbia University. For nearly six decades, Sovern was a powerful presence in the Morningside Heights community and an active member of the Law School’s full-time faculty until his death.

A longtime defender of civil rights and civil liberties, and a leading authority on labor law, Sovern developed a reputation as a master mediator. He became an expert in employment discrimination and helped to defuse a high-profile 1976 contract dispute between New York City and its transit workers, as well as mediating other labor disputes involving the city’s fire and police departments.

“It is difficult—perhaps impossible—to fully capture all that Professor Sovern meant and contributed to the Law School and the university more broadly over many decades,” said Gillian Lester, Dean and the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, in a message to the Law School community. “I will cherish his mentorship, which he offered to so many with generosity and kindness, and continue to draw inspiration and motivation from his commitment to this great institution.”

Sovern was born in the Bronx on December 1, 1931, and remained a lifelong New Yorker. His parents, Lillian and Julius, worked as a bookkeeper and a clothing salesman, respectively. He attended the Bronx High School of Science and enrolled at Columbia College in the fall of 1949, graduating summa cum laude in 1953.

Sovern went on to attend Columbia Law School, where he graduated first in his class and served as articles editor of the Columbia Law Review. In 1957, just two years after graduation, he joined the Law School faculty, becoming a full professor three years later.

Sovern’s book Legal Restraints on Racial Discrimination in Employment, published in 1966 by what is now called The Century Foundation, was described by former California Supreme Court Associate Justice Joseph Grodin in the California Law Review as “extremely valuable to everyone concerned with the legal aspects of discrimination in employment—lawyers, business firms, unions, civil rights organizations, individuals seeking relief, and not the least persons charged with responsibility for administering the laws.”

In 1968, when anti-war protests caused deep divisions within Columbia, Sovern’s legal and interpersonal skills proved invaluable. He decried what he called the “offensive notion” that faculty and students should confront each other as warring camps. “I cannot regard my students as adversaries; if they ever come to see me in that role, I shall leave teaching,” Sovern wrote in a January 1969 letter. He was appointed chair of the faculty executive committee that was credited with easing tensions, and his deft handling of the crisis was widely lauded by faculty, students, staff, alumni, and members of the New York City community.

In 1970, Sovern was named dean of the Law School, a role he held until 1979. He hired the Law School’s first female tenured professor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59, and its first African-American faculty member, Kellis E. Parker. He also established the Center for Law and Economic Studies, expanded the Law School’s clinical law programs, introduced small sections to the first-year curriculum, and added advanced seminars for upper-class students.

In 1979, Sovern was named provost and executive vice president for academic affairs of Columbia University. A year later, in 1980, he assumed the role of president, becoming the first Jewish president in the university’s history, and served until 1993.

Sovern is credited with numerous landmark achievements during his 13-year presidency at Columbia University. He led fundraising efforts that quadrupled the university’s endowment; opened Columbia College’s doors to women while supporting the long-term vitality of the women-only Barnard College; boosted the number of students of color; and spearheaded the divestiture of the university’s holdings in companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. He chronicled his career and life in an autobiography, An Improbable Life: My Sixty Years at Columbia and Other Adventures, published in 2014 by Columbia University Press.

Sovern announced his intention to step down in 1992, after his wife, the sculptor Joan R. Sovern, was diagnosed with cancer. (She died the following year). Sovern returned to teaching at the Law School in 1993 and remained deeply committed to Columbia, helping establish a number of scholarships for students and serving as an ambassador for the community at large.

In 1998, an anonymous donor established a professorship in Sovern’s name, which has been awarded over the years to law professors who demonstrate outstanding promise in their teaching and writing. Bert Huang, a scholar who merges empirical methods with legal analysis in the study of federal courts and civil procedure, currently holds the Michael I. Sovern chair.

Sovern was a founding member and served on the boards of the Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund (now LatinoJustice PRLDEF), the U.S. Helsinki Watch Committee (now Human Rights Watch), and the Mobilization for Youth Legal Services Unit (now Mobilization for Justice). He also served as a director of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

In 1997, Columbia Law School awarded him its highest honor, the Medal For Excellence, and in 2010 he received the Law School’s Lawrence A. Wien Prize for Social Responsibility for his contributions to the public good.

Sovern received honorary doctorates from Tel Aviv University, the University of Southern California, and Columbia University. His other awards include the Commendatore Order of Merit from the government of Italy, the Order of the Rising Sun Gold and Silver Star from the government of Japan, and the Gold Medal from the National Institute of Social Sciences. In 2018, Sovern was named a Living Landmark by the New York Landmarks Conservancy for his decades-long dedication to Columbia University, for his philanthropy, and for his service on numerous city commissions and boards. He was a recipient of Columbia’s Alexander Hamilton Medal and the Citizens Union Civic Leadership Award.

In 2008, at an international reunion of Columbia Law School graduates in London, Sovern noted that he was one of the few people to have attended both the 100th and the 150th anniversaries of the institution. “But I am convinced that Columbia’s greatest days still lie ahead,” he said. “If Goethe could finish Faust at 80 and Sophocles could write Oedipus Rex at 90, imagine what our Law School can do at 150!”

Sovern is survived by his wife, Dr. Patricia Walsh Sovern, and by his daughters Julie '80 and Elizabeth Sovern; his sons, Jeffrey '80 and Douglas; his stepson, David Wit; 10 grandchildren; and his sister, Denise Canner.