1754: Columbia University is established.

Columbia University was founded in 1754 as King’s College, which was located in a schoolhouse in Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan. As one of the oldest institutions of higher education in the United States (and the oldest institution of higher learning in New York), Columbia has shaped the laws and judicial systems of the country for more than two centuries. Founding Father Alexander Hamilton and John Jay were students.

1793: Columbia’s first professor of law leaves behind a legacy of pioneering legal scholarship.

James Kent (left) was named the first professor of law at Columbia. His seminal lectures on jurisprudence were published as the four-volume Commentaries on American Law, which influenced legal thought for generations.

1858: The newly opened Law School establishes legal pedagogy.

The Law School, one of the first independent law schools in the nation, opened its doors in 1858 as Columbia College of Law. Theodore Dwight became the school’s first warden (an earlier name for the dean) and introduced a new mode of legal pedagogy known as “The Dwight Method.” In lieu of the prevailing office apprenticeship as a means of legal education, Dwight developed a formal program of law, using lectures, examinations, recitations, quizzes, moot trials, and Socratic dialogue with the student.

1863: Law School professor drafts the first modern codification of the laws of war.

During the Civil War, Professor Francis Lieber (right)—a political philosopher and pioneering international law scholar—was commissioned by President Abraham Lincoln to draft General Order No. 100, the first compilation of laws of war, which established how soldiers should conduct themselves. Now known as the Lieber Code, the 1863 document became the foundation for future laws of war, including The Hague and Geneva Conventions.

1870 to 1880s: Alumni establish some of today’s leading law firms.

In the late 19th century, Columbia Law School graduates began to make their mark as legal entrepreneurs, establishing what would become some of the world’s largest and most influential law firms, including Shearman & Sterling, founded in 1873 by John William Sterling, class of 1867; Sullivan & Cromwell, founded in 1879 by William Nelson Cromwell, class of 1876; Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, founded in 1884 by John Woodruff Simpson, class of 1873, Thomas Thacher, class of 1875, and William Milo Barnum, class of 1879.

1882: The first African-American student graduates.1

George Henry Schanck graduated from Columbia Law School in 1882, setting a path for others to follow. The legendary actor and activist Paul Robeson graduated in 1923, and his legacy has been celebrated by the Law School’s Black Law Students Association for more than two decades with its annual Paul Robeson Conference and Gala.

1897: Columbia University moves to Morningside Heights.

In 1897, the university moved to its current location on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. McKim, Mead and White designed the neoclassical campus as an academic village to house the undergraduate college, the Law School, and other graduate schools.

1901: The inaugural edition of the Columbia Law Review is published.

The Columbia Law Review was founded in 1901 as a publication devoted to legal scholarship and legal thought. The student-run journal (one of 14 at the Law School) publishes articles by renowned legal scholars and lawyers as well as student-written notes and has for decades been one of the most widely distributed and cited law reviews in the country.

1920 to 1940s: Alumnus and former Law School dean issues pivotal opinions as a Supreme Court justice.

Harlan Fiske Stone, Class of 1898, who became dean of the Law School in 1910, was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1924. He served as chief justice of the United States from 1941 to 1946, succeeding Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, class of 1884.

1920s: Women enter the Law School and become trailblazers in law, politics, and culture.

In 1927, the first female students enrolled at the Law School, paving the way for the generations of pioneering women—from Constance Baker Motley ’46 (left), former Manhattan borough president, New York state senator, and federal judge, to Barbara Black ’55, former dean of the Law School and first female dean of an Ivy League law school, to Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59, the second woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court and the first female tenured faculty member at the Law School (1972).

1931: The Law School formally adopts a global perspective on law.

The formation of the Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law in 1931 made the Law School an early leader in the study of foreign legal systems. International law expert Oscar Schachter ’39 helped the newly formed United Nations establish itself from its inception in 1945, and later served as director of the U.N. Legal Division. He would become known as the architect of the U.N.’s legal framework.

1930s: Faculty make critical contributions to the New Deal.

In the midst of the Great Depression, Columbia Law School Professor Walter Gellhorn ’31 became one of the nation’s leading experts in administrative law. When Franklin Roosevelt became president of the United States in 1933 (following in the footsteps of his cousin and fellow former Columbia Law School student Theodore Roosevelt), many faculty members, including Adolf A. Berle, who was part of the president’s “brain trust,” converged on Washington, D.C., to help implement the New Deal.

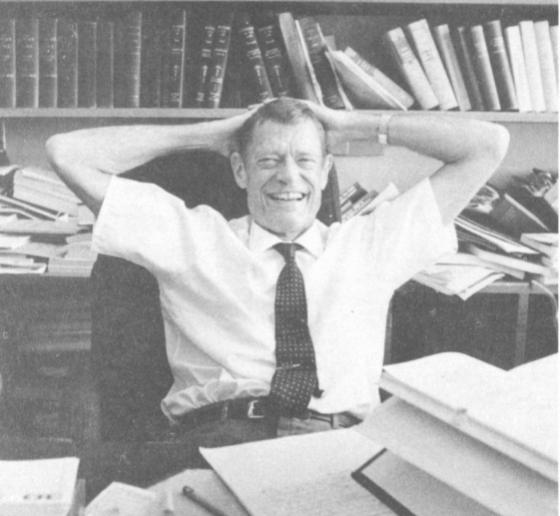

1940s: Launch of the LSAT.

Columbia Law was the driver behind the creation of the first LSAT. In 1948, after the admissions director questioned whether there might not be a better test than what was being used in 1945, Professor Willis Reese (for whom our annual teaching prize is named) developed a new test that would correlate with first-year grades rather than bar passage rates.

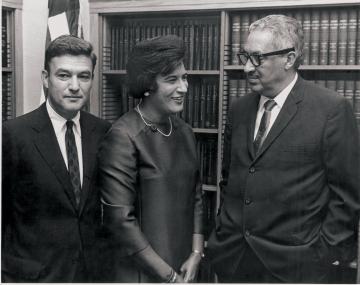

1954: Brown v. Board of Education staffs legal team with Law School alumni.

In his capacity as counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), the late Jack Greenberg ’48 (far left) successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court. The 1954 landmark decision set in motion the end of legalized segregation in America. The legal team for the case included LDF Director-Counsel Thurgood Marshall (near left) as well as Columbia Law School faculty members and alumni such as Constance Baker Motley ’46 (center), Jack Weinstein ’48, Robert L. Carter ’41 LL.M., and Professor Charles Black. Greenberg would later take over for Marshall as the head of the LDF.

1961: The Law School moves to its current home in Jerome L. Greene Hall.

The building was designed by Max Abramovitz, of the firm Harrison and Abramovitz, the same firm that designed Lincoln Center. It is named for lawyer and philanthropist. Jerome L. Greene ‘28 Jacques Lipschitz's sculpture, "Bellerophon Taming Pegasus," was commissioned for the Law School in 1964 and installed in 1977 over the western entrance. Weighing 23 tons, it is the second-largest metal statue in New York City. (The Statue of Liberty is the first.)

1970 to 1980s: The Law School becomes an international leader in human rights law.

In the early 1960s, Professor Louis Henkin joined the Columbia Law School faculty; his work would become the foundation for the study of human rights law. He co-founded Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights in 1978, then the Law School’s Human Rights Institute two decades later. In the early 1980s, the Law School established its Human Rights Internship Program, which has given more than 1,700 students the opportunity to work as summer interns with human rights organizations throughout the world. Today, the Law School provides summer funding for human rights internships in the U.S. and abroad.

1970s: Experiential learning takes a front seat.

The Law School’s clinical program, established in the early 1970s, allows students to provide legal services to underserved individuals whose cases involve a wide range of legal issues, from social justice to environmental law to community enterprise.

1975: Prominent corporate watchdog opens an interdisciplinary center for economic study.

The Center for Law and Economic Studies was founded in 1975 by the late Professor Harvey Goldschmid ’65, a leading advocate for shareholders’ rights, and Ira Millstein ’49. As a commissioner of the SEC from 2002 to 2005, Goldschmid played a significant role in developing regulations to deter insider trading.

1980s: New centers for East Asian studies foster valuable intellectual exchange.

One of the first American law schools to offer courses in Japanese law, Columbia founded the Center for Japanese Legal Studies in 1980. Our Toshiba Library for Legal Research has the largest collection of Japanese legal materials in a U.S. university. The Center for Chinese Legal Studies followed in 1983. Columbia Law School is now also home to centers for Korean, European, and Israeli legal studies.

1990s: The Law School institutes a pro bono requirement, reflecting its long-standing commitment to the public good.

In the early 1990s, Columbia Law School established the Center for Public Interest Law (now called Social Justice Initiatives) and became one of the first law schools to institute a pro bono requirement. Students must perform at least 40 hours of volunteer lawyering before graduation. Current pro bono projects send students around the globe to assist people and communities seeking access to justice.

1997: Ahead of the tech bubble, the Kernochan Center drives innovation in the IP space.

Founded in 1997, the Kernochan Center for Law, Media, and the Arts helps students navigate the ever-changing legal aspects of intellectual property in the digital age.

2000s: Study abroad opportunities open up around the globe.

In 2006, the Law School created the first ABA-approved student study abroad programs with Fudan University in Shanghai and Peking University in Beijing. Two years later, the Law School announced a global alliance with preeminent law schools in Amsterdam, Paris, and Oxford to create one-year integrated programs focusing on international criminal law, international security law, and global business law and governance.

2006: A new center launches to tackle issues facing gender and sexual justice movements.

In 2006, the Law School opened the nation’s first clinic dedicated to sexuality and gender law, which continues to provide students with training in impact litigation, legislative work, and community advocacy.

2009: The Sabin Center opens to combat climate change.

Founded in 2009, the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law leads the charge in global climate change regulation and policy. The center works with our Environmental Law Clinic and partners with Columbia University’s renowned Earth Institute.

2010: Dual degrees offer enriching interdisciplinary study.

In 2010, the Law School launched a three-year dual degree with Columbia Business School, complementing the four-year program already in place. Law School students also can take courses for credits toward their J.D. from eight of Columbia’s graduate schools, including the School of International and Public Affairs and the Journalism School.

2018: The Law School introduces a degree in global business law.

The Executive LL.M. Program in Global Business Law is the first new degree program the Law School has offered since the inauguration of the three-year joint J.D./MBA degree in 2010.

2022: The five-year Campaign for Columbia Law concludes.

Raising $325 million, the Campaign for Columbia Law, launched and completed during the deanship of Gillian Lester (who is now Dean Emerita and Alphonse Fletcher Jr. Professor of Law), realized significant accomplishments in areas of priority, including by creating more than 100 endowed scholarships and a dozen named professorships; hiring new full-time clinical faculty members who have created cutting-edge clinics; launching innovative experiential learning initiatives; and supporting a transformative renovation and reimagination of the Law Library.

2023: The Law School unveils a land acknowledgement.

Developed with input from community members across the Law School and the university, including Columbia Law’s Native American Law Students Association (NALSA), the Office of Student Services, the Office of the Dean, and the Office of University Life, the land acknowledgment plaque in Jerome L. Greene Hall memorializes the Indigenous history of Columbia’s campus and the Law School’s ongoing commitment to justice.

2024: Daniel Abebe joins Columbia as the Law School’s 16th dean.

Before joining Columbia Law School, Dean Abebe served as vice provost for academic affairs and governance at the University of Chicago, where he was responsible for stewarding critical aspects of university-wide academic life as well as important strategic assignments, such as articulating and affirming the principles of free expression and institutional neutrality. He was the Harold J. and Marion F. Green Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School and served as deputy dean from 2016 to 2018, prior to his tenure in the Office of the Provost from 2018 to 2024.

____________________________

1 Due to the absence of University records dating back to 1882, the name of Columbia Law School's first Black graduate was incorrectly listed for several years. As a result of historical research undertaken by faculty and students, this page has now been corrected to reflect that George Henry Schanck was the first Black person to graduate from Columbia Law School.