Celebrating Professor and Civil Rights Activist Kellis E. Parker

The first Black professor at Columbia Law School was a scholar, a jazz musician, and a beloved mentor to a generation of students.

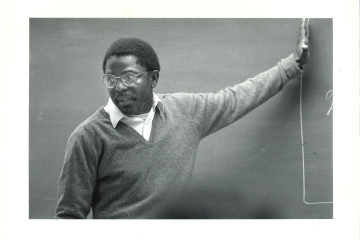

The year 1972 marked a new era for Columbia Law School. With the appointments of Kellis E. Parker as the first Black full-time professor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 as the first female tenured professor, the faculty took much-needed steps to begin to reflect an increasingly diverse student body and the society in which graduates practiced.

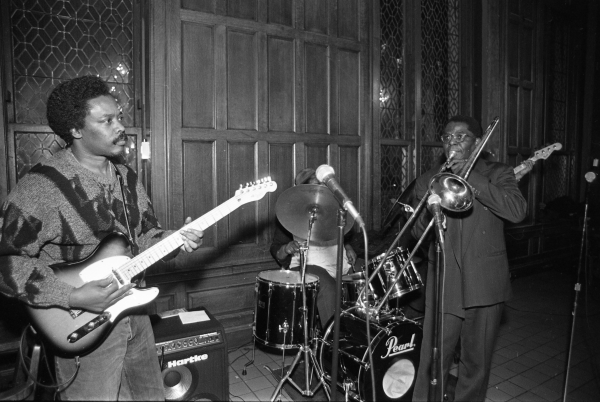

Parker was a mentor, a treasured colleague, and a legal scholar who brought a perspective grounded in both civil rights activism and musicianship. His trombone playing and his upbringing in the Jim Crow South were the basis of his scholarship, which used jazz as a framework for interpreting the law.

In his music-contracts class, Parker traced improvised, customary laws created by Black communities before and after slavery—developed in a “jam-session style of democracy” and expressed in music and literature as well as in community life—as distinct from statutory laws imposed on Black Americans to enforce white supremacy.

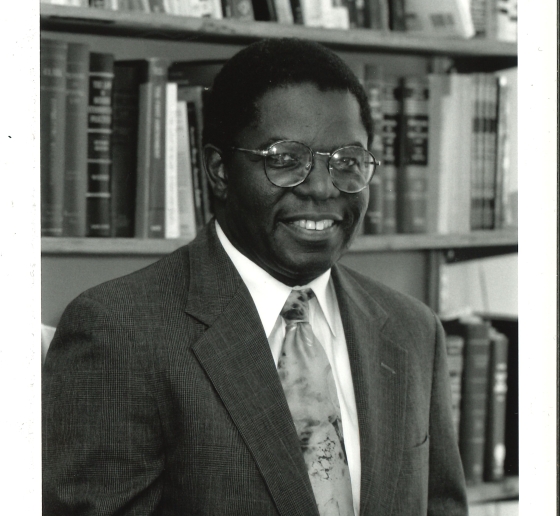

His 1975 casebook, Modern Judicial Remedies, incorporated civil rights remedies, such as continuing injunctions in school-desegregation cases, into the discussion of traditional common law remedies. Parker’s essays in law journals and other academic forums focused on the experience of Black students in legal education and the necessity of making higher education truly inclusive.

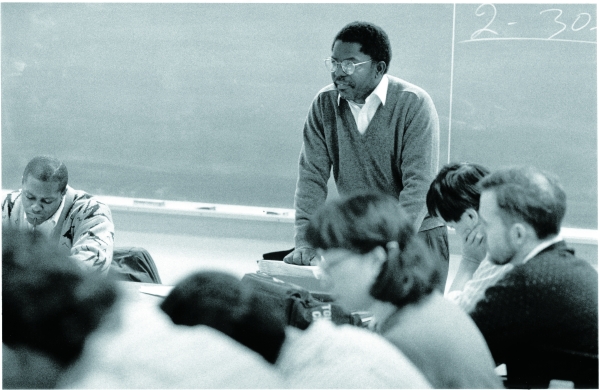

Over the course of his time at the Law School, Parker mentored a generation of students, particularly a growing number of students of color.

“He took care of us. He watched over us. He made a way for us,” said Sheena Wright CC ’90, LAW ’94 at the 2023 Paul Robeson Lecture and Alumni of Color Reception. Or, as retired Judge Rolando Acosta CC ’79, LAW ’82 put it: “He embraced us.”

Parker told students to believe in themselves, and to be themselves. “Have faith in your own intellectual worth. You are winners. You will continue to win so long as you retain confidence in your ability to do well in law school,” he said in a talk to incoming students sponsored by the Black Law Students Association. “Popular lore will tell you that excellence comes from the degree to which one approximates complete conformity. In my opinion, the students who develop their own personal touch radiate a perceptible brilliance which law professors find to be irresistible.”

Parker influenced not only his students but also his colleagues. “Kellis Parker was a teacher of intellectual liberation, a mentor who got the best from everyone, a musician who improved everybody else’s playing,” Professor of Law Eben Moglen said in a remembrance after Parker’s death. “He knew how to lead without standing in front. He could make things happen without giving directions. He made everything rhyme, without even choosing the words.”