Professors’ Amicus Curiae Briefs Shape the Law

Columbia Law faculty influence court decisions and advance legal theory when they submit “friend-of-the-court” briefs to the Supreme Court and other jurisdictions.

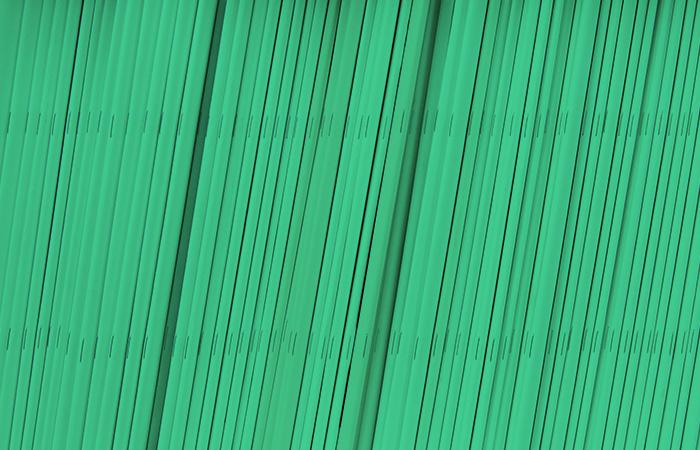

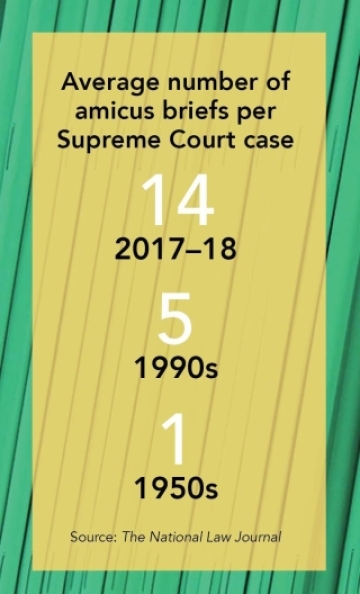

It was a milestone term for the U.S. Supreme Court in 2017–2018: Amicus curiae briefs were filed in every one of the 63 argued cases, averaging just over 14 briefs per case, a new record. These “friend-of-the-court” briefs—written by legal scholars, pro bono attorneys, government lawyers, and advocates across the political and ideological spectrum who are not party to the case at hand—have become a mainstay of contemporary jurisprudence: Submissions at the Supreme Court have increased 800 percent since 1954 and 95 percent between 1995 and 2015, a seemingly unstoppable phenomenon dubbed “The Amicus Machine” by two law professors in the Virginia Law Review.

In the latest term, the case that garnered the most briefs, at 95, was the contentious Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, which addressed the question of whether a baker could refuse to make a wedding cake for a gay couple by claiming that doing so would violate his religious beliefs. One of those briefs was written by Columbia Law School Professor Katherine Franke on behalf of 15 minority faith-based organizations and the school’s Public Rights/Private Conscience Project (which has been renamed the Law, Rights, and Religion Project).

Franke, a leading scholar of LGBTQ rights and co-director of the Law School’s Center for Gender and Sexuality Law, framed the stakes in the Masterpiece case as not only undermining LGBTQ rights but religious liberty itself. She offered the court a disquisition on the role of anti-discrimination laws to protect the rights of religious minorities and argued that religious liberty must be “harmonized” with principles of equality. “We took the position that these are mutually reinforcing values, and we were pleased to see that the Court’s decision embraced this approach, despite narrowly ruling for the baker,” says Franke, referring to how Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion rested on a finding—one Franke would take issue with—that members of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had manifested hostility toward the religious views of the baker. Still, the court made clear that it was not opening the door to discrimination based on religious belief, and Franke applauded Kennedy’s “soaring language recognizing the importance of gay rights.”

Franke is one of several Columbia Law School faculty who frequently file amicus briefs at the Supreme Court and in other jurisdictions not only to influence decisions but also to provide critical links between cutting-edge legal scholarship and how judges apply the law on myriad topics including arbitration, climate change, due process, freedom of speech, immigration, and transgender rights. The professors’ varied perspectives—historical, political, sociological, philosophical, procedural—can be as integral to an opinion or dissent as those submitted by attorneys on behalf of petitioners and respondents.

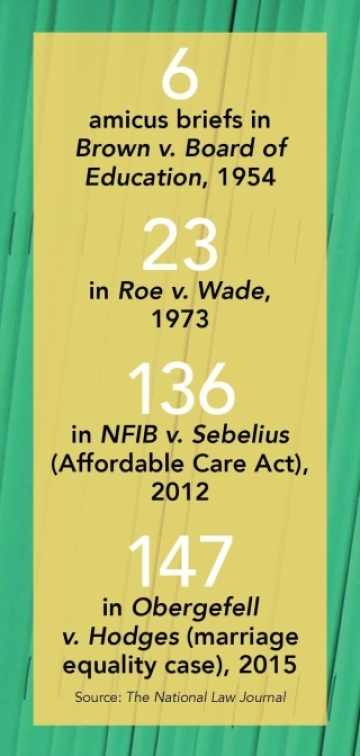

The overall impact of amicus briefs on the Court’s rulings is impossible to calculate, but the number of times the justices refer to them in oral arguments and written opinions is an indicator of their effectiveness: According to an annual report of the Supreme Court amici docket by attorneys Anthony Franze and Reeves Anderson of Arnold & Porter in The National Law Journal, the justices cited amicus briefs in the 2017–2018 term in 23 majority, 21 dissenting, and five concurring opinions.

“The advantage of an amicus brief is that it’s not abstract. You’re seeking to develop the law in the context of a case that has already been brought,” says George A. Bermann, the Jean Monnet Professor of EU Law, Walter Gellhorn Professor of Law, and director of the Law School’s Center for International Commercial and Investment Arbitration. Indeed, he knows his brief in Henry Schein Inc. v. Archer & White Sales Inc.—in which he offered a new paradigm for interpreting a provision of the Federal Arbitration Act—was persuasive because Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 and Stephen Breyer cited it during oral arguments in October 2018. Although the court did not decide the specific question Bermann raised when it ruled on Jan. 8—it was not argued by counsel and did not need to be decided—the professor says, “What is interesting is that the court specifically flagged the issue in its opinion and suggested that it warranted consideration by the Court of Appeals on remand. After all that, it is all but certain that the issue will finally rise to the surface and get addressed.”

“Surgical Strikes”

“I think of amicus briefs as surgical strikes,” says Suzanne Goldberg, the Herbert and Doris Wechsler Clinical Professor of Law who co-directs the Law School’s Center for Gender and Sexuality Law and directs the Sexuality and Gender Law Clinic. She writes briefs to complement the primary lawyers’ arguments or amplify their position. “I want to make one point very clearly using case law or other sources that the court does not already have.”

In the past six months, Goldberg filed two briefs in federal courts opposing the Trump administration’s ban on transgender people serving in the military. In her brief for Jane Doe 2 v. Donald J. Trump, Goldberg focused on the flaws in the February 2018 memorandum by then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis, which provided the administration’s foundational justification for the ban. “My goal was to show that the report was based on very traditional and long-since-rejected sex stereotypes,” she says.

In the 2017 immigration case Sessions v. Morales-Santana, Goldberg worked with sociologists on a social science brief to dispel the premise of a provision in the Immigration and Nationality Act that treated mothers and fathers differently. “There were only one or two legal citations in it. The main point was to show the court that unmarried fathers do not typically disappear from their children’s lives, because the implication of the law we were challenging is that they do,” she says. Ginsburg invoked the brief in an opinion that struck down this sex-based discrimination, observing that “unwed fathers assume responsibility for their children in numbers already large and notably increasing.” Goldberg adds, “So sometimes the goal of an amicus brief is to rebut a common assumption. Other times, the goal is to help a court see an issue in a broader frame.”

Beyond the Headlines

Amicus briefs on hot-button social issues—such as immigration, abortion, marriage equality, and health care—are often deliberately written to garner media attention and sway public opinion, which can affect the thinking of a court. However, most appellate and Supreme Court cases focus on narrow and arcane areas of law, and thus the majority of amicus briefs do not make news because they are too esoteric for non-lawyers to understand.

Bermann, for example, says the brief he submitted in Republic of Sudan v. Harrison, which was argued before the Supreme Court on Nov. 7, is of modest interest to the public. The case, he explains, is about interpreting a statute that determines when and how foreign governments can be sued in U.S. courts under an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. “This may appear at first glance to be something of a technical issue, but a moment’s reflection tells us that U.S. foreign relations themselves are implicated,” he says.

Gillian Metzger ’96, the Stanley H. Fuld Professor of Law, read stacks of amicus briefs when she was a Supreme Court clerk for Ginsburg during the 1997–1998 term. As a legal scholar, she also has written briefs, including two for Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the landmark 2016 case about whether the state of Texas had passed laws that placed an undue burden on women seeking an abortion. The first brief was “on a very dense federal courts matter” at the certiorari stage, when the Supreme Court decides whether to accept a case. “It was helpful for civil procedure and federal courts scholars to provide an argument explaining why the court could hear this case,” she says, noting that the brief was cited by Justice Breyer’s majority opinion.

The other Whole Woman's Health brief was written with support from other constitutional law scholars. It analyzed the controlling framework that the Court established in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey in 1992, when the court reaffirmed the central holding of Roe v. Wade that guaranteed a woman’s right to have an abortion before viability without undue interference from the state. “We were able to focus on slightly more abstract arguments than the parties in the case could,” says Metzger.

Scholarship or Activism?

Franke has recently authored several amicus briefs to provide federal court judges with an architecture for interpreting the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). “As legal scholars of religious liberty, it is our concern that RFRA is interpreted consistently across contexts where sincerely held religious beliefs are substantially burdened by government action,” she says.

This fall, she and seven other scholars of religious liberty law filed briefs in support of neither side in two cases in which the federal government is prosecuting members of the group No More Deaths/No Más Muertes—a ministry of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Tucson—for allegedly “harboring migrants” by leaving food and water for them in a federally controlled wildlife area. The group maintains that its religion’s respect for the sanctity of human life compels its members to assist anyone—including migrants—who is in dire circumstances. “We note in the brief that the Justice Department has taken a position in this case that is much less protective of religious liberty than it has in cases more aligned with the administration’s political agenda,” says Franke. The case is expected to go to trial in early 2019.

Some academics question the scholarly value of writing amicus briefs. However, Bermann and his colleagues think such criticisms are misguided. “I absolutely view them as a form of scholarship,” he says. “While the exercise is very case-specific, it crystallizes what are invariably matters of broader interest and resonates with the scholarship and teaching we perform. I also do not mind in the least getting in the trenches.”

Metzger considers her amicus briefs an essential intellectual exercise. “I only write in areas where I am an active scholar,” she says. “My scholarship informs my briefs, and writing briefs informs my scholarship.”

She and other professors engage students in researching and writing briefs. For example, two members of the Environmental Law Clinic drafted an amicus brief that helped secure a significant environmental victory this summer when a federal court ordered the Environmental Protection Agency to ban a toxic pesticide linked to brain damage in children. Writing briefs is also a major component of Goldberg’s Gender and Sexuality Law Clinic. “It’s a fantastic opportunity for students to take a deep dive into an important legal issue and to learn broader advocacy skills,” she says. “It’s fundamental to the work we do in the clinic that is based on the idea of multidimensional lawyering.”

Goldberg considers writing amicus briefs a professional and moral obligation. “The goal in filing is to achieve a more just society,” she says.

# # #

Published January 18, 2019