Policing

What reforms follow the decline of stop and frisk?

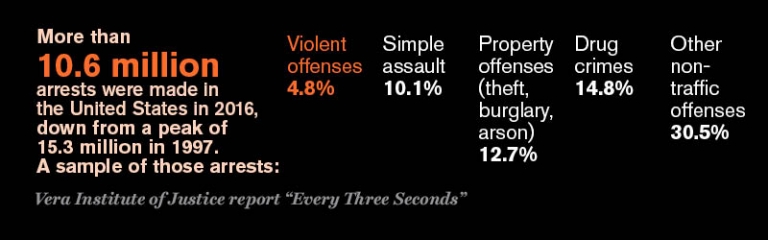

The steep drop in crime in the United States over the past 25 years has coincided with the spread of a style of policing that aggressively enforces low-level offenses (turnstile jumping, public urination) to deter more-serious crimes. The effectiveness of the so-called broken-windows strategy is disputed and controversial, but such enforcement remains significant: Over 80 percent of the 10.6 million arrests in 2016 were for low-level, nonviolent crimes, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, which tracks arrest data.

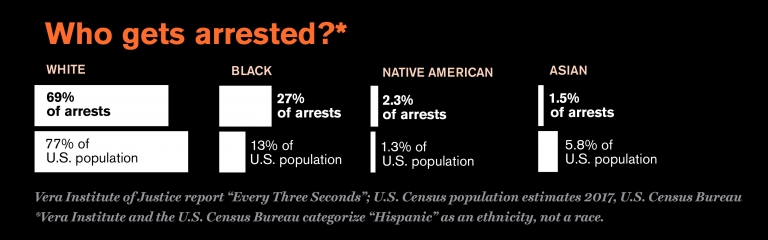

Research by Professor Jeffrey A. Fagan showing racial bias and ineffectiveness in police stop-and-frisk tactics was key in Floyd v. City of New York, a 2013 federal class action against the New York City Police Department. Fagan’s work led to a dramatic decrease in the use of stop and frisk. His research in New York and in Ferguson, Missouri, after the 2014 death of Michael Brown, also documents the crushing effect of broken-windows policing on low-income communities and among blacks and Hispanics. Vigorous enforcement can lead to “legal proceedings that over time evolve into tougher penalties that leave criminal records with lasting consequences,” he says.

“The model of intensive face-to-face physical contact between police and civilians is outmoded,’’ Fagan says. “There needs to be experimentation in different policing models. We can substitute smart analytics for heavy-handed police tactics.”

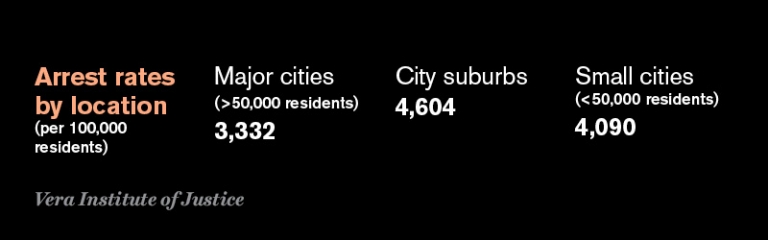

Professor Justin McCrary’s research has shown that the mere presence of police in a neighborhood reduces crime, but the challenge remains in determining how to police in high-crime areas where residents feel simultaneously underprotected and overpoliced. “People tend to have both mind-sets: ‘I need the police, but they also just roughed up my brother for no good reason,’” McCrary says. “Police departments need to engage with their communities in a way that actually makes them feel protected.”

“In some ways, you’re asking police to do things that are inconsistent with what they are sworn to do, which is simply to enforce the law. But you can’t have blinders on. What is, at the end of the day, the best solution? What is the fair solution? What’s going to be the best resolution? It may not simply be to just enforce the law as it’s written.” —Former U.S. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. ’76, on the arrests of two African-American men for sitting at a table at Starbucks