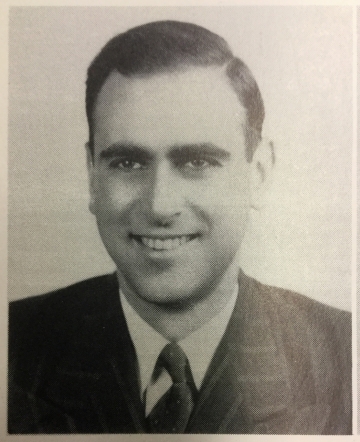

In Memoriam: Jack B. Weinstein ’48

A legal lion, the legendary long-serving federal judge, venerated Columbia Law School professor, and active alumnus, dies at age 99.

Jack B. Weinstein ’48, a member of the Columbia Law School faculty for nearly 50 years, the longest-serving federal judge in U.S. history, and champion of such causes as gun control, parole reform, and school desegregation, died on June 15, 2021. He was 99.

In an extraordinary career as a practitioner, professor, scholar, and judge, Weinstein was a towering and colorful figure who was never shy with his views. He was an authority on civil procedure, evidence, and New York State civil practice whose jurisprudence and leadership over many decades had a profound influence on the legal community.

“Jack Weinstein was a one-of-a-kind jurist, a humanist who embodied the highest ideals of Columbia Law School,” said Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law. “His unyielding commitment to the fair administration of justice, the rule of law, and to training law students to make a difference in the world was an inspiration to generations of Columbians. And his legacy serves as a reminder that the law is, and forever will be, a noble profession.”

“I’m convinced our country is bound to equalize, democratize, and to save with love, not hate.”

—Jack B. Weinstein

As a U.S. district judge in the Eastern District of New York for 53 years, Weinstein presided over tens of thousands of cases, including important litigation against tobacco companies and lawsuits in which Vietnam War veterans claimed harm from the use of the chemical defoliant Agent Orange. He revolutionized mass tort litigation with innovative procedural devices, including the use of “special masters” to help oversee complex, multiparty lawsuits. In his writings and rulings on scientific evidence, Weinstein paved the way for expert testimony in trials, which is now commonplace.

In his final ruling, in January 2020, Weinstein wrote that the New York City Fire Department (FDNY) must allow four African American firefighters with a rare skin condition to keep their beards, despite an FDNY rule that firefighters must be clean-shaven.

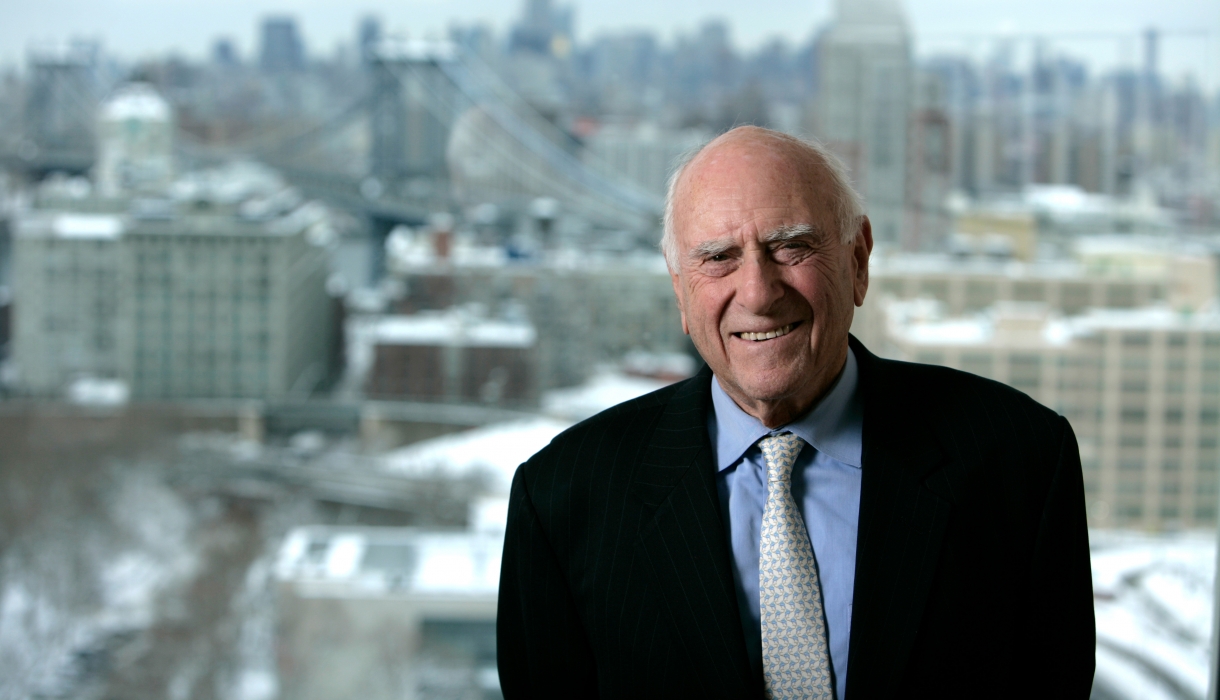

At the time when Weinstein stepped down from the bench and entered inactive service in February 2020, at the age of 98, he was the longest-serving federal judge in U.S. history. His family had encouraged him to retire decades earlier. “My children want me to retire,” Weinstein told The New York Times in 1991. “But they don’t realize how much fun I’m having.”

Justice and Compassion for All

Weinstein was known for his spirited judicial decisions and for his unpretentious, compassionate manner toward all parties in litigation. In bench trials, he took a seat at a conference table with counsel; in jury trials, he occasionally sat in the box with jurors; and at sentencing hearings, he sometimes held the hand of the defendants appearing before him. He rarely found occasion to don the black robe that comes with a seat on the bench—except when his mother stopped by his courtroom. “The marshals would call up and tell my secretary, ‘Tell the judge his mother is coming up,’” Weinstein told the American Bar Association’s Litigation magazine in 2013. “And I’d have to put my robe on.”

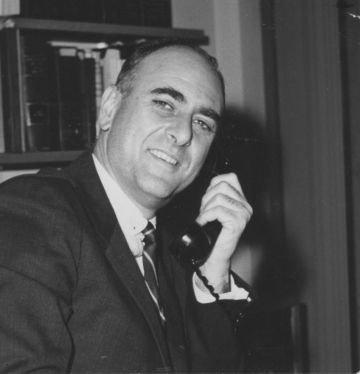

Weinstein was appointed as a judge to the Eastern District of New York by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 on the recommendation of New York Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, for whom he had worked as an adviser. He served as chief judge from 1980 to 1988. After he took senior status in 1993, which allows a jurist to reduce their caseload, Weinstein continued to oversee a mostly full docket.

Weinstein was known for speaking out on controversial issues—including the disproportionately small number of women in leading roles at trials and other court proceedings and overly harsh sentences in drug and other criminal cases—and he often used his written opinions as advocacy. (The New Yorker said in 1993 that he “wielded the Constitution like a sabre”.) He was a supporter of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, who directed the founding of the Chabad-Lubavitch-affiliated Aleph Institute, the leading Jewish organization caring for the incarcerated and their families.

But he was influential behind the scenes as well. He appointed special masters to help manage hundreds of lawsuits by thousands of Vietnam veterans claiming that the defoliant Agent Orange caused cancer, birth defects, and other health problems. He negotiated with the plaintiffs and chemical companies, which agreed to settle the litigation for $180 million in 1984.

A Lifetime of Hard Work

Weinstein was born on August 10, 1921, in Wichita, Kansas, where his parents had moved to help care for a widowed aunt of Weinstein’s. When he was 5, his father—who emigrated from Hungary as a child—and his Brooklyn-born mother moved the family back to Brooklyn. The family struggled during the Great Depression, and Weinstein often recalled how he had worked from the time he was a young boy, delivering milk at 4:30 in the morning behind a horse-drawn carriage, and later, while in college, working on trucks and docks at night. After his father lost his job at the National Cash Register Company, Weinstein said the family ate food that “fell off a truck” for a while.

Weinstein attended Brooklyn College at night and earned his bachelor’s degree in 1943. He then enlisted in the U.S. Navy, where he served from 1943 to 1946, including on the USS Jallao (SS-368) submarine in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, where he participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Weinstein credited the military with teaching him to be a leader. “I had learned how to command, which stood me in great, good stead when I was a professor at Columbia and when I worked in the courtroom,” he said in a U.S. Courts profile in 2014. “I was in full command of that courtroom and I have been since, just as I was when I was at the conning tower in the middle of the night standing watch. The ship was mine, the courtroom was mine, the classroom was mine. I had to make immediate decisions, and I knew they would be followed.”

While in the Navy, Weinstein tried to figure out what he wanted to do next in life. His mother, whom he described as a “voracious reader,” sent him a copy of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s The Common Law, and he “decided law would be an interesting thing to study.”

Shaped by Columbia Law

Weinstein had no familiarity with the law or lawyers when he began his free legal studies at Columbia Law School, courtesy of the GI Bill. Weinstein said at a reunion in 2014 that he had “Never seen a lawyer before, and the first lawyer I saw was Herbert Wexler,” 1931 Columbia Law graduate and longtime professor of constitutional law at the Law School. “There was Wexler exercising the Socratic method. After 10 minutes of that, I was ready to go back to the war.”

Weinstein’s first of three sons was born during his first week at Columbia—“between the lecture on Development of Legal Institutions at 9:00 to 10:00 and the lecture on Civil Practice from 11:00 to 12:00.” He and his first wife, Evelyn Horowitz Weinstein, a social worker who earned her master’s degree from Columbia University in 1944 and worked with World War II veterans, shared child-care duties, switching when she went to work or he went to school. (Evelyn died in 2012 at 89.)

In 1949, Weinstein secured a clerkship with New York State Court of Appeals Judge Stanley H. Fuld ’26 and a year later opened his own law practice in Manhattan—in part because anti-Semitism at the time made finding work at a firm difficult. He had served as a lecturer at Columbia Law School after graduating in 1948, and, when he was offered the opportunity to teach in 1952, he jumped at the chance.

He became a full professor in 1956 and continued to teach in that capacity until his appointment to the federal bench in 1967. He remained a member of the adjunct faculty until 1998, teaching Evidence to hundreds of law students, including U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59. He also taught Judges Anita B. Brody ’58 and Robert Sack ’63, who joined him for the panel “Judging Without Trials” during the 2013 Columbia Law reunion weekend. Sack recalled waking up early three days a week for Weinstein’s civil procedure class. “Had I known that at any time in my lifetime I was going to be on a panel of judges, sitting next to Jack—on the same side of the table—I would have happily done it seven days a week at two in the morning,” he said.

Weinstein wrote or co-wrote several books, including Federal Evidence: Commentary on Rules of Evidence for the United States Courts, which became a leading casebook on that topic; Elements of Civil Procedure: Cases and Materials; Individual Justice in Mass Tort Litigation: The Effect of Class Actions, Consolidations, and Other Multiparty Devices; and Weinstein, Korn & Miller, a multi-volume treatise on New York civil practice.

“Students loved him,” said Columbia Law Professor John C. Coffee Jr., who co-taught classes with Weinstein and was appointed by Weinstein as a special master in a sweeping lawsuit against Big Tobacco. “The man is both a brilliant jurist and a person of extraordinary empathy,” he said in an interview with NY1 News in February 2020.

While Weinstein was on the faculty at Columbia Law School, he assisted the lawyers at the NAACP on Brown v. Board of Education at the suggestion of Professor Walter Gellhorn ’31, although Weinstein always maintained that his own role was minor.

“I was able to help in a way that I thought was of no great importance . . . doing the kind of work that a young associate would do: preparing briefs and research,” he said. Thurgood Marshall “was very gracious in putting my name on the briefs in the Brown case. Something I didn’t deserve, but I did spend a lot of time there, working with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund team while I was teaching.”

Once on the bench, Weinstein quickly earned a reputation for his willingness to try new things in the search for justice. In addition to his role in the Agent Orange case, he ordered New York City officials to desegregate Mark Twain Junior High School in the 1970s (the order stayed in place until 2008) and restructured a trust set up by the Manville Corporation to compensate workers for asbestos-related injuries.

Weinstein never seemed afraid to go his own way: In 1993, he made a decision to stop presiding over drug cases to protest sentencing policies. Once he began accepting them again, he still made news: In 2018, he issued a ruling declaring he would no longer send people on supervised release back to prison for marijuana violations. But his creativity also meant he was often reversed. In 2002, he certified the first ever nationwide punitive-damages class in a case against tobacco companies; three years later, a unanimous panel of the 2nd Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned that decision.

A Man of Many Parts

Weinstein “had many incarnations—teacher, scholar, judge” said U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer in a 1997 issue of the Columbia Law Review dedicated to Weinstein. “He has served in each role with distinction,” wrote Breyer. “Throughout, he has maintained an unswerving commitment to the ordinary citizen. He has not lost a sense of a common bond with the people our justice system serves.”

A devoted member of the Columbia Law School community, Weinstein returned regularly to campus. He introduced, moderated, and spoke at countless events and panel discussions and delighted in staying connected to faculty and students. He hired, trained, and mentored more than a dozen Law School graduates who went on to become successful lawyers and leaders in the profession.

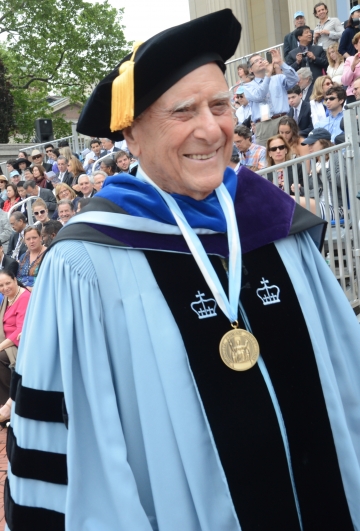

Weinstein received the Columbia Law School Medal for Excellence in 1990. In 2008 he was awarded the Association of American Law Schools’ inaugural Section on Evidence Wigmore Award. In 2013, he was honored with the Law School’s Lawrence A. Wien Prize for Social Responsibility and the Columbia Alumni Association’s Alumni Medal in recognition of his service to the university. In 2017, to mark Weinstein’s half century on the bench, the Eastern District named its ceremonial courtroom for the judge. Most recently, he was awarded the 2021 Prosser Award from the AALS Torts and Compensation Systems Section.

When he retired and entered inactive service in February 2020, he told The New York Times that he remained optimistic about the future of the United States despite increasing political polarization. “I’m convinced our country is bound to equalize, democratize, and to save with love, not hate,” he said. “We’ve come so far toward equalization. The country has changed so enormously for the better. Now, yes, it is going downhill. But I’m convinced that we will come together. It’s essentially a good country made up of people who will fight for what’s right.”

Weinstein is survived by his wife, Susan Berk, his three sons—Seth, Michael, and Howard—and two grandchildren.

As a recipient of the 2013 Columbia Alumni Association Medal for Distinguished Service, Jack B. Weinstein ’48 gives an interview in Columbia’s Kent Hall—home of the Law School when he was a student—about how Columbia Law shaped his life and career.

Read a tribute to Weinstein on the one-year anniversary of his passing, written by Andrew W. Siegel of Siegel & Coonerty.