Juvenile Justice

Why are police arresting so many children of color?

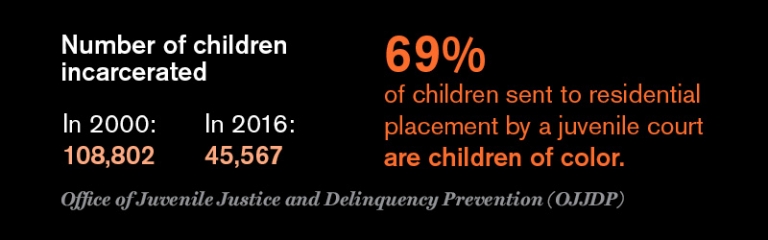

Although the overall incarceration rate has increased nationwide, the number of children locked up in the United States has fallen by more than 50 percent since 2001. But as in the larger criminal justice system, a disproportionate number of them are children of color.

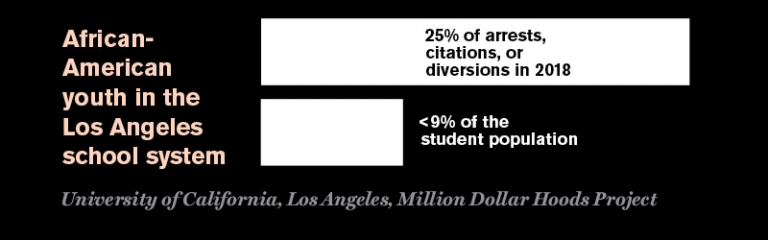

Research shows that racial disparity in arrests especially among African-American youth drives the disproportionate incarceration rates, says Associate Clinical Professor Colleen Shanahan ’03, who has documented the impact of juvenile court fees on low-income families of color. “The question becomes, what explains the racial disparity in arrests?”

In schools, for one, zero-tolerance discipline policies and more police officers have created a school-to-prison pipeline in which students accused of misbehavior—a situation that is itself subject to racial bias—end up in juvenile court. Girls of color face harsher school discipline than their white peers, as Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw detailed in her 2015 report “Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced, and Underprotected.”

But many states have recognized the enormous expense of juvenile detention facilities and their failure to prevent repeat offenses. Alternatives like community-based programs and smaller group-living facilities prioritize age-appropriate rehabilitation. The sharp decrease also reflects a developmental model of juvenile justice—much of it based on work by Professor Elizabeth Scott—that recognizes that a significant portion of juvenile crime is due to adolescent immaturity.

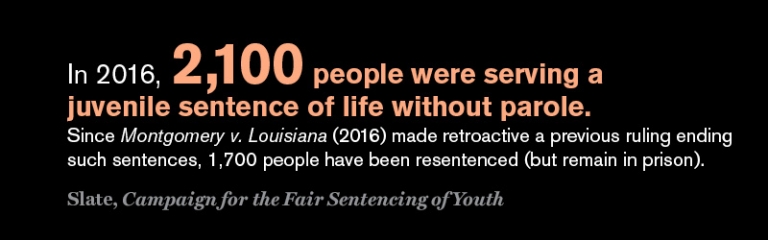

This newer approach to young offenders has support across the political spectrum because it is “more effective and cheaper than locking kids up, which is more likely to result in kids’ engaging in a life of crime,” Scott says. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Roper v. Simmons that the death penalty for juveniles is unconstitutional. The court cited “Less Guilty by Reason of Adolescence,” a 2003 journal article Scott co-wrote. In 2012, citing Roper and Scott, the court held that juveniles could not be subjected to a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without parole. The court adopted Scott’s argument that adolescents are less culpable than adults because their brains are not fully formed, and therefore they deserve less punishment.

“Safety does not exist when black and brown young people are forced to interact with a system of policing that views them as a threat and not as students. . . . Police in schools is an issue of American racial disparity that requires deep structural change.” —Judith Browne Dianis ’92, executive director of the Advancement Project, in the report “We Came to Learn: A Call to Action for Police-Free Schools”