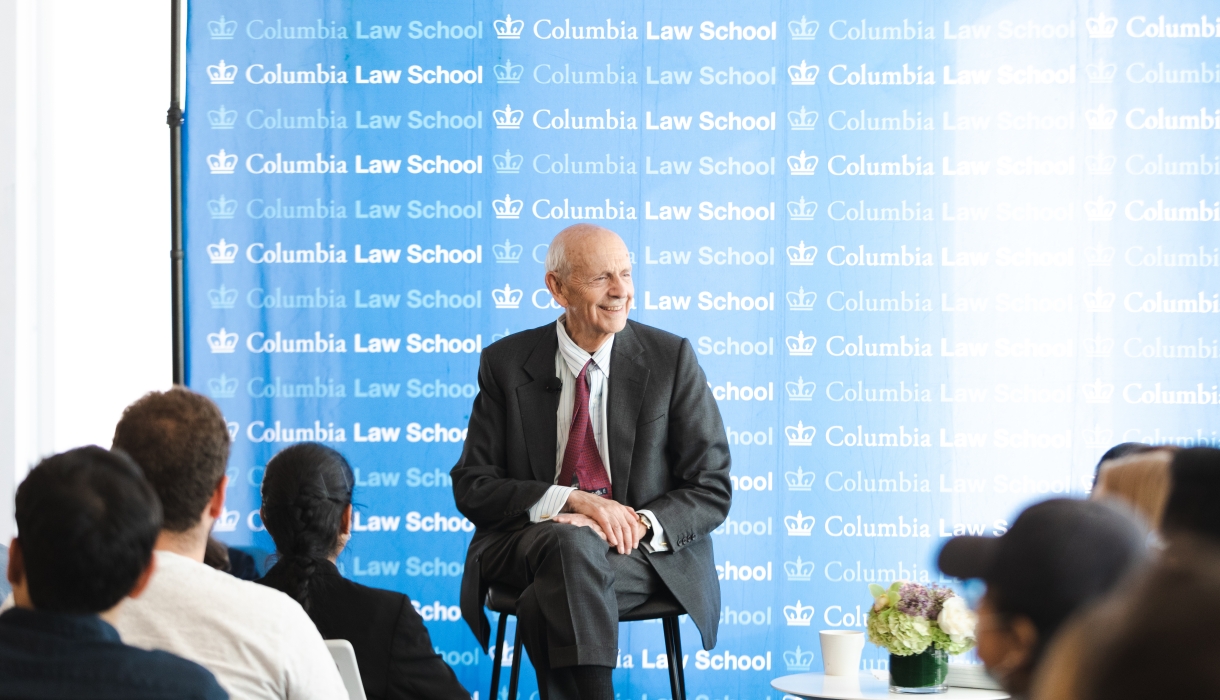

Justice Stephen G. Breyer Visits Columbia Law School

Students had the opportunity to hear the retired Supreme Court justice speak at a variety of events, including a fireside chat featuring his former clerks who are now on the Law School faculty.

Retired Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer visited Columbia Law School in April, sharing with students accumulated wisdom from his distinguished career as a professor, a U.S. Department of Justice lawyer, a counsel to the U.S. Senate, a federal appeals court judge, and a justice on the high court, where he served from 1994 to 2022.

On April 13, Columbia Law students attended an intimate fireside chat with Breyer and faculty members who had clerked for him: Kathryn Judge, Christina D. Ponsa-Kraus, Thomas P. Schmidt, and Timothy Wu. The following day, he joined Professor George A. Bermann for a keynote conversation that was the capstone of the Law School’s International Arbitration Association’s annual Columbia Arbitration Day event. He also participated in an April 19 roundtable discussion organized by Columbia University’s Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, “People, Rule of Law, and Supreme Courts Now,” moderated by Professor Jessica Bulman-Pozen in conversation with judges from Germany, Italy, and Portugal.

During the fireside chat at the Law School, he shared anecdotes, hypotheticals, and philosophical insights with his trademark humor, warmth, and perspicuity. One important lesson he highlighted came from his time as chief counsel to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee when it was chaired by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. Breyer recalled that Kennedy told him that the first thing you should do when you think you are absolutely right about something is to find an intelligent person you respect who thinks the opposite. “You sit down with somebody on the other side and talk to them—no, you don’t talk to them; you try to get them to talk as much as possible,” Breyer advised his audience. “And if they talk for long enough, you’ll find something you agree with. And once you find something you agree on, you can say, ‘Let’s work on that.’ And sometimes, when you start to do that, you end up with something that’s better than you thought you might get.”

Working in the Senate also influenced Breyer’s approach to statutory interpretation, which “always depends on context,” he told the students. “See what the consequences are. See what the legislative history is—very unpopular at the moment, but I think it’s important. See what the problem was in the hearings, in the newspapers, what led Congress to act.”

Breyer provided insight into his experience on the Supreme Court and how the justices discuss cases in conference. He explained that after the chief justice offers a summary of the issues in a case and how he is leaning, each justice, in order of seniority, gets to speak. “Nobody speaks twice until everyone’s spoken once,” he said. “That’s a very good rule for any small group.”

Students, many of whom are planning to clerk after graduation, said they were awed, entertained, and encouraged by hearing from the justice in person. “He’s a true storyteller—you could listen to him all day,” said Valeria Flores-Morales ’23, a member of the inaugural class of the Columbia Clerkships Diversity Initiative (CDI). She said she enjoyed hearing Breyer talk about interactions with his fellow justices. “You could tell they all held a lot of respect for each other, even when they disagreed.”

During the fireside chat, Dylan McDonough ’24 asked Breyer about his experience as a Supreme Court clerk for Justice Arthur Goldberg during the 1964–1965 term. Breyer spoke of witnessing how the 1954 landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education, which declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, did not actually lead to widespread desegregation. “It taught him that Supreme Court rulings were not enough,” said McDonough. “This, [Breyer] seemed to be saying, fed into the pragmatic approach he often took once he became a Supreme Court justice. As a 2L in the process of applying for clerkships now, it was fascinating to hear about how these early experiences can shape your entire career and perspective on the law.”

Erik Ramirez ’24 said hearing Breyer speak and getting to ask him a question was a highlight of his law school career thus far. He was most impressed by Breyer’s vision of what it means to be an activist judge.

“The popular image of an activist judge is a stubborn provocateur, but Justice Breyer had a different take—he described an activist judge as someone willing to make necessary compromises and do as much good as they possibly can in each decision,” said Ramirez, who is also a CDI scholar. “He said something along the lines of 20% of your goal will always be better than zero. That’s a clearly pragmatic position, but it also reflects a deep optimism. What I get from that line is that you can’t let your inability to change everything stop you from changing something, and it's a lesson I will certainly try to carry forward.”

Olivia D. Martinez ’23, another CDI scholar, said seeing Breyer in person was a “meaningful and symbolic” culmination of her three years at Columbia Law School.

“As the first in my family to attend law school, I had never before imagined I’d be in the same room as and listening to a talk from a retired Supreme Court justice,” said Martinez. “As I come to the end of my law school career and prepare to begin working, I remember his sentiment that despite the difficult times we’re in, our generation of upcoming lawyers is a reason to have hope for a better, more just future.”