Chinese Legal Studies Center Named for Hong Yen Chang 1886, the First Chinese Lawyer in the U.S.

A successful $5 million fundraising effort will endow the center in Chang’s name and bolster groundbreaking U.S.-China legal research and programming.

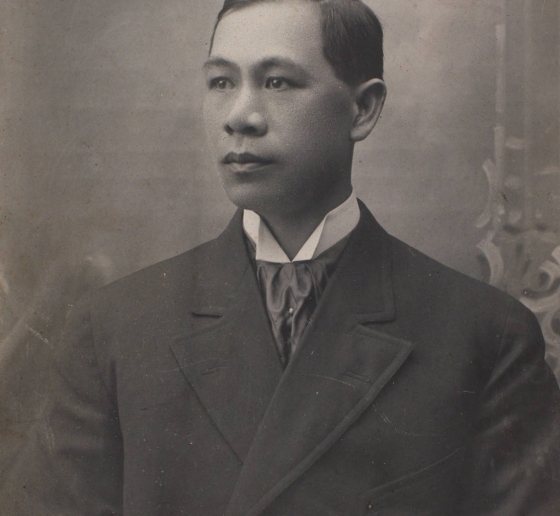

Pictured: Hong Yen Chang, circa 1890, around the time he moved from New York to California, hoping to practice law. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, announced that Columbia Law School’s Center for Chinese Legal Studies will be named in honor of the school’s first Chinese graduate, Hong Yen Chang, who graduated from Columbia Law School in 1886 and later became the first Chinese American to be admitted as a lawyer in the United States. As of January 1, 2021, the center will be known as the Hong Yen Chang Center for Chinese Legal Studies (张康仁 中国法律研究中心).

The naming is made possible through a new $5 million endowment led by Tim Steinert ’89, former general counsel of Alibaba Group, and his wife, Lixia Zhang. The fund garnered nearly 100 other contributions from dedicated Law School alumni, including leadership donors Li Lu ’96, Chun Wei ’84 LL.M., Charles Li ’91, Tim Xia ’97, Jon Christianson ’89, and Wei Sun Christianson ’89.

The first academic center of its kind in the United States, Columbia Law’s Center for Chinese Legal Studies was founded in 1983 by R. Randle “Randy” Edwards, Walter Gellhorn Professor Emeritus of Law, a preeminent authority on Chinese law. Under his leadership, the center produced influential scholarship, fostered scholarly exchanges between China and the United States, and trained generations of students in Chinese law.

“For many of us, the Center for Chinese Legal Studies, previously under the inspiring leadership of Professor Randy Edwards, has been the foundation of our careers at the intersection of U.S.-China legal and business relations,” said Steinert, who serves on the Columbia World Projects President’s Council. “Randy’s contribution to mutual understanding between the two countries has been enormous.”

Today, the center is a world-renowned intellectual hub, bringing together law students and scholars from around the world and supporting research and programming in Chinese Law and related topics. It also serves as a focal point for Chinese students and for China-related activity at Columbia.

“I am deeply grateful to our alumni for their generous support,” said Benjamin L. Liebman, Robert L. Lieff Professor of Law and the center’s director since 2002. “Our community has been strengthened immeasurably by generations of students and scholars from China, as well as by generations of Asian Americans. How fitting, then, that we name the center in honor of our very first Chinese student, someone who overcame numerous barriers to become the first student from China and first Chinese American admitted to practice law.

“The center’s work remains as vital today as it has ever been,” said Liebman.

The endowment will allow Columbia Law to expand offerings of events related to Chinese law, with a particular focus on deepening linkages between academia and real-world problem-solving. It also will assure that the school can continue to cultivate generations of scholars of Chinese law.

“The study of international and comparative law, particularly Chinese law, has long been a source of pride for Columbia,” said Dean Lester. “This new endowment is an opportunity to herald the often-overlooked legacy of a pathbreaking Columbia Law alumnus in Hong Yen Chang and to further the work that Professor Edwards began almost 40 years ago: to bring members of the U.S. and Chinese legal communities together to generate a deeper, more common understanding. It is also a sign that Columbia Law School will continue to be open to students from around the world, including China, who add so much to our community.”

Chang was born in Guangdong, China, in 1859 or 1860, and, after his father died, came to the United States in 1872 as part of the Chinese Educational Mission, a program to educate outstanding Chinese boys with academic promise. He attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, as well as Yale College, prior to enrolling at Columbia Law School. He graduated with high honors in May 1886, and after a two-year pursuit to be admitted to the New York Bar—drawn out due to the discrimination he faced on the basis of race—he was finally admitted by a special act of the New York State legislature in 1888.

In hopes of serving the large Chinese community of San Francisco as a lawyer, Chang moved to California in 1890 and sought admission to the California State Bar, but he was denied under the federal Chinese Exclusion Act.

Despite this significant setback, Chang went on to chart a successful and distinguished career in diplomacy, banking, and academics. Early in his career, he joined the Chinese Diplomatic Service, rising to the role of chargé d'affaires at the Chinese embassy in Washington, D.C. He was a banker and then taught trainees of the Chinese navy in Berkeley, California, until his retirement in 1920. He died in 1926 in Berkeley, leaving a wife, Charlotte Ah Tye Chang, and two children, Ora and Oliver.

In 2015, Chang was granted posthumous admission to the California State Bar, following advocacy efforts by the University of California, Davis School of Law’s Asian Pacific American Law Students Association, and the group’s faculty adviser, Professor Gabriel “Jack” Chin. The petition they submitted to the Supreme Court of California was supported by then–Columbia Law School Dean David M. Schizer and was granted by the court in a landmark March 15, 2015, decision. In re Hong Yen Chang on Admission (60 Cal.4th 1169 [2015]) overturned the 1890 decision that had stood for Chinese racial exclusion in the law for 125 years.

“On behalf of the Hong Yen Chang descendants, we humbly thank Columbia Law School for the unexpected and enormous honor of bestowing my ancestor’s name to the distinguished Center for Chinese Legal Studies,” said Rachelle Chong, Chang’s great-grandniece and a nationally known California regulatory attorney who was herself the first Asian American appointed to both the Federal Communications Commission and the California Public Utilities Commission. “Without question, Hong Yen Chang would have been delighted that the center would bear his name, as he spent most of his life bringing together American and Chinese lawyers, diplomats, politicians, and businesspeople in the furtherance of mutual understanding and peaceful interaction.”

Explore More

“Hong Yen Chang, Lawyer and Symbol”

By Gabriel J. Chin, Asian Pacific American Law Journal, Volume 21 (2016)

“Pioneers in the Fight for the Inclusion of Chinese Students in American Legal Education and Legal Profession”

By Li Chen, Asian American Law Journal at Berkeley Law, Volume 22 (2015)