Activist on the Global Stage: Paul Robeson 1923

His pathbreaking career was nearly crushed by McCarthy-era ostracism, but Paul Robeson’s voice, in song and speech, continues to be heard in support of Black freedom.

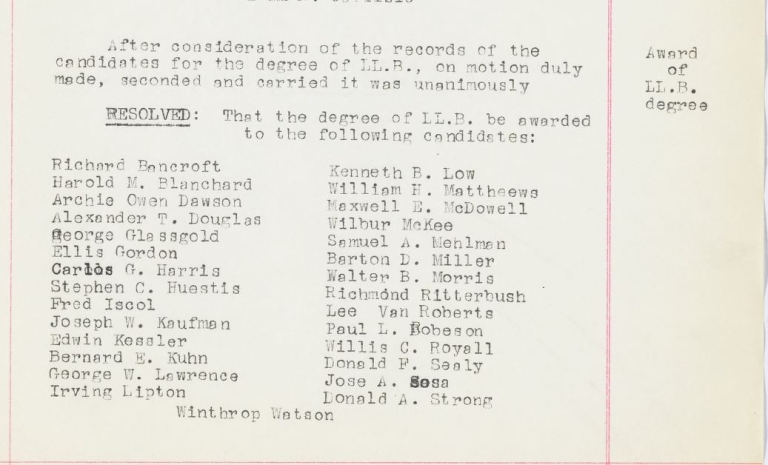

Actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson 1923 broke racial barriers and enthralled audiences even before he graduated from Columbia Law School. His long performing career, which included starring in Othello on Broadway and singing “Ol’ Man River” as Joe in the 1936 film Show Boat, brought him worldwide acclaim. But his support of the Soviet Union as a socialist and anti-racist society, and his activism for progressive causes—from Black civil rights to Spanish Republican fighters to postcolonial African nationalism—cost him dearly during the Cold War.