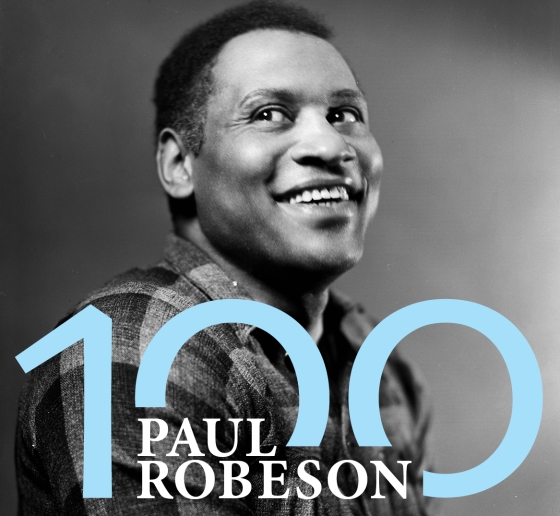

Exhibition: Paul Robeson 100

On display in the lobby of Jerome L. Greene Hall, the exhibition celebrates the life of Paul Robeson 1923, who graduated from Columbia Law School a century ago.

Visit the exhibition in Jerome L. Greene Hall and find additional information about each panel below.

Finding a Home in Harlem

Paul Robeson 1923 was born in Princeton, New Jersey, the youngest son of Presbyterian minister Rev. William D. Robeson and Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson. His father, who had been enslaved in eastern North Carolina, escaped with his brother Ezekiel on the Underground Railroad to Pennsylvania in 1858.

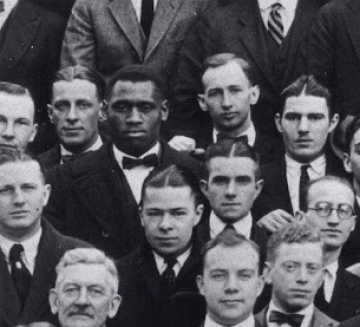

Robeson distinguished himself as a scholar and an athlete at Somerville High School and Rutgers University, where he received a scholarship. The third Black student at Rutgers, he was a 13-letter athlete and a collegiate football All-American, was named a Phi Beta Kappa scholar, and was inducted into the Cap and Skull Society—an honor reserved for only four graduating students each year. In his 1919 valedictory address, Robeson referenced the racism met by Black service members returning from World War I and charged his audience to join the “fight for the great principles for which they contended, until in all sections of this fair land there will be equal opportunities for all, and character shall be the standard of excellence.”

In spring 1920, Robeson enrolled at Columbia Law School. Finding a home uptown during the unfolding Harlem Renaissance, Robeson became a regular attendee at gatherings of artists and writers held at the home of NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson, who penned the lyrics to “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” To cover his expenses, Robeson worked part-time as an assistant coach to Fritz Pollard, head coach of the Lincoln University football team. During a temporary pause in his law courses, Robeson and Pollard, who later became the first Black head coach in the NFL, played professional football for the Akron Pros and later the Milwaukee Badgers.

Robeson also found himself in the same social circles with his future wife, Eslanda “Essie” Cardozo Goode, who was the head histological chemist for New York Presbyterian Hospital and distant cousin of future Supreme Court Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo. Described by her son as “boldly assertive, a go-getter,” Eslanda became Paul’s partner, manager, and advocate. They married in 1921 and made a new home together at 321 West 138th St.

Robeson earned an LL.B. from Columbia Law School in February 1923. He was hired by Rutgers alumnus Louis William Stotesbury, whose firm specialized in estate law. Though praised by Stotesbury for the quality of his legal work, Robeson faced harsh racial discrimination in the workplace. After a white stenographer refused to take dictation from him, Robeson brought the treatment to the attention of Stotesbury. Though he vowed to address the specific treatment, Stotesbury cautioned Robeson of the pervasive racism that awaited him in trying to represent white clients. Stotesbury offered Robeson an opportunity to open an office in Harlem to represent a Black clientele, but Robeson declined and resigned his position. His son later said, “It was inconceivable to Paul that he would enter a profession in which his possibilities would be so limited by racial prejudice.”

Star of Stage and Screen

In Harlem, Robeson was frequently invited to sing at social and cultural events. After getting a taste for the theater at the Harlem YMCA, he appeared in Taboo at the Sam H. Harris Theater in April 1922. “I knew little of what I was doing, but I was urged to go ahead and try,” said Robeson about his debut. “So I found myself in rehearsal. What was most important at that time was that I got about $75 a week, which a law clerk didn’t get for quite some time. And I remember the first night after I’d played the role. I came back to the Law School and Dean [Harlan Fiske] Stone, who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was standing in the door. He looked at me, and he said: ‘Robeson, what have you been doing?’ And he had some newspapers in his hand, and I was rather frightened. The dean says: ‘Well, I read some nice things about you here—they say you’re a very fine actor.’”

After a glowing recommendation from a Taboo colleague, Robeson was invited by Eugene O’Neill to audition for his new play, All God’s Chillun Got Wings. He was swiftly cast in the lead role. He later starred in The Emperor Jones and appeared in his first film, Body and Soul, by the independent Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. Robeson’s bass-baritone voice gained him international name recognition. After the birth of his son in 1927, Robeson was cast by Florenz Ziegfeld in the London production of Show Boat. His performance of “Ol’ Man River’’ was hailed as the highlight of the show.

Throughout his early career, Robeson fought an internal struggle in accepting roles featuring racist stereotypes. He navigated critique of these performances by describing them as a constructive, if flawed, means to elevate Black performers in a constrained set of opportunities. In his concerts, he featured Black spirituals in an effort to reclaim and add nuance to the performance of these pieces.

During the 1930s, Robeson performed in the U.S., Europe, and the Soviet Union. He also appeared in film adaptations of some of his signature performances, including Show Boat and Emperor Jones. In Jericho, Robeson, who played a Black soldier in Algeria in WWI, was finally allowed to exert a measure of control, rewriting the ending of the script to show his character’s triumph.

Robeson’s devotion to knowledge grew along with his fame. He was a student of languages (some reports say he was fluent in 10 languages), political philosophies, and geopolitics. He began to speak frequently in support of anti-colonial and anti-fascist causes, including during performances in Spain and a tour of Scandinavia where his program was pointedly anti-Nazi. In a 1937 interview, Robeson declared, “Democracy should be widening, but instead a drive is being made to subjugate not only my group but all oppressed groups throughout the world.”

In 1943, Othello opened on Broadway with Robeson in the title role opposite Uta Hagen and José Ferrer. It still holds the record for the longest run of a Shakespeare play on Broadway.

A review in the Boston Herald remarked that Robeson’s “very presence on stage heightens the power of the drama and makes the final tragedy wholly inevitable and deeply moving. Where most Othellos fail, Paul Robeson succeeds, fully and completely.” During the national tour, Robeson’s contract excluded appearances in racially segregated venues; performances in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., were canceled along with a concert at the White House in demonstration against segregation in the nation’s capital.

‘The Artist Must Elect to Fight for Freedom’

The Robesons returned to New York in 1939 as war spread in Europe to remake their home and advocate for the advancement of Black America. He became an ally of the Franklin Roosevelt administration in rallying Black support for the war effort through his performances at war bond rallies and military bases along with a radio program, “Ballad for America.” But he focused his message on gaining victory on two fronts: the war against fascism abroad and against segregation at home.

In January 1941, the first note appeared in Robeson’s FBI file, and he became a person of interest to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. His file eventually included thousands of documents tied to his activities in the Soviet Union, his critique of American segregation, and his statements advocating resistance against war with the Soviet Union. Robeson’s view that America had no right to call Black servicemembers to armed conflict when their rights continued to be deprived ignited a fiery public reaction and became a topic for the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He was vilified in much of the press—Hearst newspapers nationwide dubbed him “an undesirable citizen.” In Peekskill, New York, rioters hurled rocks at concertgoers as they exited the venue of one of his performances. Reverend David Jemison said, “It is not Paul Robeson, the Communist, that they fear. It is Paul Robeson, the champion of the cause of Black people in America and in Africa.”

In 1950, Paul Robeson’s passport was revoked and the U.S. State Department issued a notice to prevent him leaving the country, citing that his travel abroad “would not be in the best interests of the United States.” Though his career was stifled by the travel restrictions and the public attempts to discredit him because of his ties to the Soviet Union, Robeson continued to speak out against injustices. In June 1956, Robeson was called to testify before HUAC. He fielded questions for an hour and was defiant in his refusal to answer questions on the Communist Party, instead commenting on race relations in the United States. When asked why he chose not to live in the Soviet Union, he replied, “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?” The committee voted to cite Robeson for contempt, but he was hailed in the Black press as a hero. A headline in the Baltimore Afro-American read, “Mr. Robeson Is Right.”

In 1958, after an eight-year battle, the U.S. Supreme Court in Kent v. Dulles overturned the State Department regulations denying passports to those suspected of communism. Invitations poured in for Robeson to perform internationally, and he resumed his appearances in Europe and Australia until his health began to deteriorate. After the death of Eslanda in 1965, he kept a close circle of friends but largely retired from public life. At a star-studded event at Carnegie Hall celebrating his 75th birthday—and organized by Harry Belafonte—Robeson sent a message of thanks: “I want you to know that I am the same Paul, dedicated as ever to the worldwide cause of humanity for freedom, peace, and brotherhood.”

Robeson died at age 77 in Philadelphia. In his eulogy at Mother AME Zion Church in Harlem, Paul Robeson Jr. said, “My father’s legacy belongs also to all those who decide to follow the principles by which he lived. It belongs to his own people and to other oppressed peoples everywhere. It belongs to those of us who knew him best and to the younger generation that will experience the joy of discovering him.”