Sarah A. Seo ’07 Joins Law Faculty

Her book on the history of policing and cars illuminates the legal decisions that have led to ‘driving while Black.’

Legal historian Sarah Seo ’07 compares her research to an hourglass. Her initial curiosity about a big topic narrows to a specific question and then broadens again as she finds answers to that question and explores its ramifications.

That’s how Seo’s curiosity about law enforcement and the war on drugs led to a focus on Fourth Amendment search cases and then to the confluence of two quintessentially American phenomena: the ubiquity of cars and the perniciousness of racial discrimination.

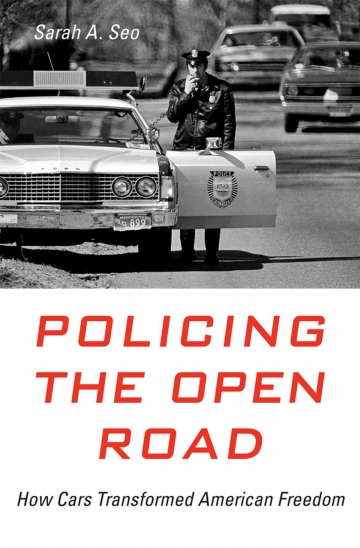

Seo, who joins the Columbia Law faculty July 1, examined the legal history of automobiles and driving in Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom, published in 2019. The award-winning book was noted in The New Yorker and named one of the year’s 10 best history books by Smithsonian Magazine.

Seo was drawn to the subject when she noticed that the number of Fourth Amendment cases soared in the 1920s, when car ownership became widespread. “When there’s an explosion of cases on one legal issue, it usually reflects a transformation in American society. In the 1920s, the relationship between citizens and the police was changing because of the automobile,” she says.

Widespread car ownership and the need to regulate traffic brought many more citizens into contact with police officers for the first time. Because of drivers’ pervasive disregard for the traffic code, officers were granted additional powers to deal with the difficulties of managing traffic. At the same time, police policies encouraged officers to exercise judgment when handling traffic violators who were, presumably, otherwise law-abiding citizens. Seo’s book explains how procedures that were designed to mediate police interaction with drivers in fact gave officers discretionary power that ended up being used to discriminate against people of color and the poor. The leeway that allows a police officer to let a motorist go with just a warning can also be used for “pretextual policing”—a traffic stop that turns into a search and drug arrest.

How the history of the automobile led to “driving while Black” became clear as she worked on the project, says Seo, who has been teaching at Iowa Law School. “When I first started researching, I didn’t know how the governance of automobility would play into the history of race and policing in this country. I didn’t expect to find that the need to deal with the ‘law-abiding’ traffic violator had been a foundational moment for modern policing. It helps explain what we are seeing today.” For many people, the first encounter with the criminal justice system begins with a traffic stop, Seo notes.

Seo’s current research also stems from questions about the war on drugs and its ramifications for the legal system. She is looking at the history of U.S. conspiracy laws, beginning with the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. Today, a conspiracy charge is often included in drug cases, Seo says, because it is easy to prosecute and to obtain a guilty plea. “There’s a long history of bringing conspiracy charges against many different individuals, from labor organizers during the first Red Scare to executives of large corporations accused of anti-competitive tactics at the height of the Cold War. Now it’s minority teens suspected of gang activity during the war on drugs,’’ Seo says. “I want to know, what does the use of conspiracy laws to go after such a wide range of individuals and groups reveal about American governance? And what do these conspiracy cases reveal about contested notions of American values in the political economy?”

Seo earned her doctorate in history at Princeton and first taught at Columbia Law in the spring of 2019, when she served as a visiting associate professor. Columbia Law’s strength in legal history drew her back to Morningside Heights for good. “Columbia Law has recruited an amazing group of legal historians who study a diverse range of topics and time periods. I’m thrilled to join this group,” she says. She also values the interaction with the criminal law faculty. “They make me a better historian. Their scholarship about what’s going on today raises historical questions for me,’’ she says. “What’s exciting about being a historian at a law school are the opportunities to talk about history and what’s going on today at the same time. Being part of that conversation gives me a focus and a purpose for what I do as a historian.”

Seo grew up in College Station, Texas, where her family settled after emigrating from South Korea when she was 5 years old. A pianist, she considered studying music as an undergraduate before focusing on history. Today, Seo continues to play the piano in part because she finds it a useful way to let her research organize itself in her thoughts. “Taking a break to let my mind think in a different register is important to my writing process,” she says.

Also crucial to her writing are her daily afternoon walks with her Maltipoo, Grimke. In fact, they ventured to Manhattan’s Riverside Park every day during the summer of 2017, when Seo wrote the manuscript for Policing the Open Road. “We miss Riverside Park,” Seo says. “Grimke and I can’t wait to be full-time New Yorkers again.”