Keeping Democracy Within the Lines

Ruth Greenwood ’09 LL.M. works to take the partisanship out of electoral redistricting by litigating to oppose gerrymandering.

When she prepared to leave her native Australia to begin studying for her LL.M. degree, Ruth Greenwood envisioned her year at Columbia Law School as one of “educational indulgence.” This was her chance, she says, to attend “the best teaching institution I could think of. I promised myself I wouldn’t take on too many extracurricular activities because I wanted to just enjoy learning from amazing experts.” Once on campus, she reveled in classes with professors like Olatunde Johnson, whose Senate legislative experience she admired, and Jamal Greene, whose writing style she loved.

But beyond intellectual exploration, Greenwood’s LL.M. year set her on a new and serious mission: to improve voting rights in the United States. She is now co-director for voting rights and redistricting at the Campaign Legal Center, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization, where she works to combat potential gerrymandering—the practice of drawing districts to gain advantage for one political party—when Congressional and state legislative districts are redrawn based on the 2020 Census.

Greenwood’s path began during an “inspiring” Law School class taught by election law expert Nathaniel Persily, then the Charles Keller Beekman Professor of Law. She discovered that election law combined all her interests: constitutional law, numbers, analytics, and U.S. politics. “I used to meet up with other students at Sydney University, and we would talk about what was going on in American politics.” The class reinforced her interest.

She focused her studies on election law, and after receiving her LL.M. degree, hustled to find a job at an election law nonprofit. She worked on election law policy at the Fair Elections Center and Democratic National Committee in Washington and then segued into litigation at the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law before joining the Campaign Legal Center in 2016.

Greenwood quickly narrowed her policy focus to gerrymandering because of its outsize effect on election outcomes. Enactment of voter ID laws and purges of voting rolls in advance of the 2020 elections have drawn media attention and litigation. While those acts create “real barriers,” for voters, Greenwood says, they skew election outcomes only by small margins. “With gerrymandering, the percentages that we look at are 10 and 15 percent skewed toward one party or another,” she says. “That’s a huge distortion.”

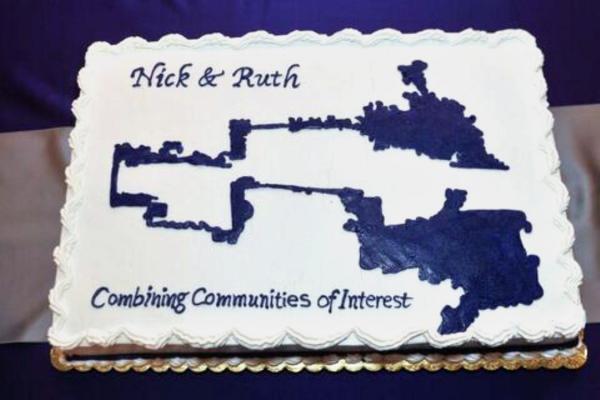

Gerrymandering is old enough to be named for the 18th-century politician and former Vice President of the United States Elbridge Gerry. Defeating it has proved to be an uphill battle. Greenwood represented plaintiffs in Rucho v. Common Cause and Gill v. Whitford, two gerrymandering cases that reached the Supreme Court. In Rucho, North Carolina’s 2016 Congressional map, drawn by a state legislative committee, had been held by a federal district court to unconstitutionally favor Republicans. Gill arose from a 2011 Wisconsin state legislative map that was held by a federal district court to be unconstitutional partisan gerrymander in favor of Republicans. But in June 2019, the Court ruled 5–4 in Rucho that federal courts could not intervene in partisan gerrymandering. Gill was also dismissed as a result.

“It would have been nice to have this single, very big case make a massive change. Sadly, that’s not going to happen,” Greenwood says.

Instead, Greenwood now is focusing on efforts to take redistricting out of the hands of the state legislature and establish independent redistricting commissions instead. In 2018, four states passed ballot initiatives creating such commissions to handle redistricting, which occurs every 10 years. For states that don’t have a commission ballot initiative, Greenwood hopes that “if they are adopting redistricting plans in 2021, we can convince them to say, ‘For 2031, we’ll change to a commission.’”

Both Republicans and Democrats draw gerrymandered districts when they can get away with it, Greenwood says. And because 36 states currently have single-party control of the legislature and governor’s seat, each party will likely have the opportunity to try to redistrict in their own favor in 2021. “And I will be trying to stop them,” she says.

Greenwood also works to promote state and local adoption of ranked-choice voting, which allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate wins more than 50% of first-choice votes, an instant runoff occurs, in which the candidate with the lowest number of first-choice votes is eliminated and the second-choice votes on those ballots are counted. The process is repeated until a candidate wins a majority of votes cast.

Ranked-choice voting is now used in some elections in 24 states, but only Maine has adopted it for all elections. Using ranked-choice ballots has been shown to increase the election of people of color—which is important to improve diversity in representation in areas where residential integration has made it more difficult to draw a majority-minority election district, Greenwood says. “The reality is that even in places where you see less residential segregation—in the Southwest, Phoenix, Dallas, Los Angeles—you still do see racial polarization in voting. It means that people of color, who are in the minority, can’t get their candidate elected.”

Greenwood’s arrival at Columbia Law School in 2008 coincided with the election of President Barack Obama. This year, she will be eligible to vote for president for the first time; she obtained her U.S. citizenship last year while on parental leave. (Baby Iliana beat mom to citizenship by two weeks.) But Greenwood retains a global perspective on her work.

“It matters to me that America is a functioning democracy because it’s not just America that is affected by American democracy—it is the whole world,” Greenwood says, “and so I don’t think of myself as just a U.S. citizen helping my country. I think of myself as a person of the world, trying to make sure that if we call ourselves a shining beacon of democracy, we actually are a democracy.”

Update: On February 26, Greenwood was named the inaugural director of the Voting Rights Litigation and Advocacy Clinic at Harvard Law School.