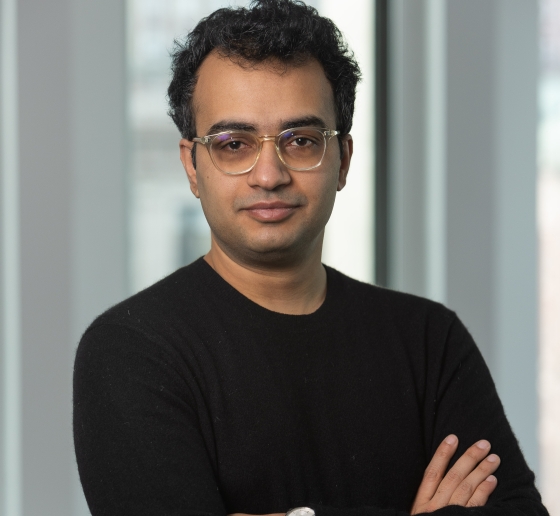

Comparative Constitutional Law Scholar Madhav Khosla Joins Faculty

A leading thinker on comparative constitutionalism who has a Ph.D. in political theory, Khosla has written extensively about the seminal role of the Indian Constitution in the evolution of democracy around the globe.

In his most recent book, India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy (Harvard University Press, 2020), Madhav Khosla makes a case for the singularity of India’s Constitution, which went into effect on January 26, 1950, defying what some political theorists considered insurmountable odds.

“In the mid-19th century, there were people who believed that democracy could not exist in several countries—for cultural reasons, for reasons of education, poverty, ethnicity, and so forth,” says Khosla. “A hundred years later, the constitutional moment that changed that is the Indian one. It was the first major political effort in the history of the world to actually create self-government under conditions that were widely thought to be unfit for self-government.”

Khosla, who joined the Columbia Law faculty as an associate professor of law on January 1, says India’s hard-won independence from Britain was very different from what happened two centuries before in the United States. “If the American Constitution and founding were about the question, ‘Can democracy exist anywhere?’ then the Indian Constitution and founding were about the question, ‘Can democracy exist everywhere?’” he says.

“The interesting thing about India,” he continues, “is that constitution making and democratization went together . . . creating universal suffrage for everybody at a time when many believed that the entire population was not actually capable of voting. The line I use in my book is, ‘In a way, what was being attempted was to create democratic citizens through democratic politics.’”

Finding Constitutional Law

When Khosla, who grew up in New Delhi, enrolled in the National Law School in Bangalore, he didn’t have a clear idea of what aspect of the law to pursue professionally. “Law just seemed like something very interesting to study,” he says. “It seemed like a window into understanding the world, a prism for grasping certain kinds of human behavior.”

After law school, he worked at a federal commission examining the relationship between India’s central and state governments, which deepened his interest in federalism. He came to the United States to get an LL.M. at Yale, which led to his desire to study political theory. He returned to work at a think tank in India for a year before enrolling at Harvard, where he earned a Ph.D. in political theory in 2017. His dissertation, Modern Constitutionalism and the Indian Founding, was awarded the Edward M. Chase Prize for “the best dissertation on a subject relating to the promotion of world peace.”

Khosla first came to Columbia Law School in 2018 as the Ambedkar Fellow in Indian Constitutional Law. (Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the fellowship’s namesake, earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University and was chairman of the Indian Constitution’s drafting committee.) Khosla was also a visiting professor at the Law School in the fall of 2019 and spring of 2021, teaching Comparative Constitutional Law and two seminars: The Crisis of Constitutional Democracy and Law and Authoritarianism, which he co-taught with Benjamin L. Liebman, Robert L. Lieff Professor of Law and director of the Law School’s Hong Yen Chang Center for Chinese Legal Studies.

A New Intellectual Home

Khosla will be teaching torts and comparative constitutional law in the fall of 2022 and describes Columbia as an ideal home for him as a scholar.

“Above all, what’s exciting to me about the Law School is that it has one of the best public law faculties in the country,” he says. “There are few faculties that would push you in the way that this one will if you’re interested in thinking about public law in conceptual and theoretical terms.”

“Above all, what’s exciting to me about the Law School is that it has one of the best public law faculties in the country.”

The opportunity to make New York City his home is another reason why teaching at Columbia appealed to him. “I’m looking forward to being part of a remarkable intellectual community, not just at the Law School and the broader university, but in the city in general, which is home to some of the world’s most powerful minds, and, of course, wonderful things like museums and classical music.”

Although he is far from his homeland, the fate of Indian democracy is always on his mind. “Whether or not the experiment works, it’s a novel experiment,” he says. “In the face of a number of other postcolonial countries, India’s track record has been astonishingly successful. I think it would be fair to say that India today faces grave concerns about democratic stability and liberal freedom.”

Of course, many of the world’s democracies are facing existential crises. “I think all democracies can learn from one insight that emerged during the founding of the Indian Constitution, which is that democratic citizenship is something that needs to be constantly created,” Khosla says. “It’s something that needs to be generated and regenerated.”

How do Indian and American democracy compare at this moment in history? “It’s hard to compare in synoptic ways, but I would say that both countries today face profound challenges,” he says.

In a recent speech, Khosla said the greatest threat to democracy is not extremism but a certain kind of anti-constitutional cynicism. “Thinking constitutionally is the way to change the world in peaceful ways,” he says. “Constitutionalism is about collectively exercising agency and shaping the world.”