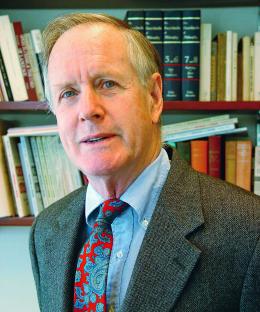

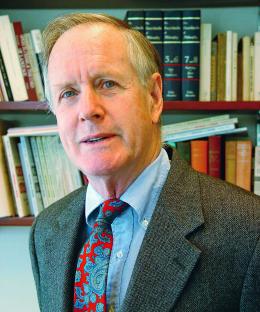

R. Kent Greenawalt ’63, a renowned authority on constitutional law and legal philosophy who wrote prolifically and profoundly about religion, freedom of speech, and constitutional theory over the course of his five-decade-long career as a Columbia Law School professor, died on January 27, 2023. He was 86.

Greenawalt, who served as deputy solicitor general in the U.S. Department of Justice from 1971 to 1972, was revered for his ability to apply legal reasoning and analytical thinking to controversial and charged subjects, such as people’s religious beliefs, as well as for his ability to do so with empathy and kindness. His own faith, which he once described as having “uncertainty and tentativeness,” guided him in those efforts as a member of what he admitted is a “pervasively secular discipline.”

“My convictions tell me that no aspect of life should be wholly untouched by the transcendent reality in which I believe, yet a basic premise of common legal argument is that any reference to such perspective is out of bounds,” Greenawalt wrote in his 1988 book, Religious Convictions and Political Choice. “This personal and professional dilemma helps explain my concern with the place of religious convictions in the process by which laws are made.”

Greenawalt—who held the prestigious title University Professor, Columbia University’s highest academic honor—made lasting contributions to the law and legal scholarship. In its 2013 decision upholding the use of race in college admissions, Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the U.S. Supreme Court quoted an article Greenawalt had written nearly 40 years earlier, “Judicial Scrutiny of ‘Benign’ Racial Preference in Law School Admissions.” In the article, Greenawalt argued “racial preferences for minority groups can be sustained as permissible ways to redress injustices and to promote genuine social equality” but should not be used if other “non-racial” methods are available.

The care with which Greenawalt treated these subjects and others—including jurisprudence, legal interpretation, and criminal responsibility—did not go unnoticed. During a 2015 celebration marking his half-century on the faculty at Columbia Law School, his colleagues and other prominent scholars discussed his work during a daylong conference and praised him personally and professionally in written tributes.

“It is not an overstatement to say that his writing has shaped the discourse within constitutional law and First Amendment law,” Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, said at the time. “Kent unfailingly brings an ethos of kindness, of courtesy, of decency to the life of this law school. He’s generous in reading others’ work; he expresses disagreement with a velvet hand; he unfailingly raises the tone of our discourse. He has truly shaped the field.”

In 2016, Greenawalt received the Columbia Law School Association Distinguished Columbian in Teaching Award (pictured above), which is presented annually to honor graduates who, through excellence in teaching, scholarship, and writing, as well as achievements in a chosen field, have brought distinction to the Law School and the faculties on which the individual has served.

Vincent Blasi, Corliss Lamont Professor of Civil Liberties and a First Amendment expert, wrote that when he read Greenawalt’s 1989 book, Speech, Crime, and the Uses of Language, he deemed it “the best book about the First Amendment” he had ever read. Blasi added that he still recommends his students read Greenawalt’s “classic” Columbia Law Review article “Free Speech Justifications,” more than 25 years after it was first published.

On matters of church and state, Greenawalt also excelled.

He “did not get the memo that law isn’t reason and religion can’t be dealt with reasonably,” wrote H. Jefferson Powell, a professor at Duke University School of Law. “Instead, he went about proving both convictions dead wrong.”

At Columbia Law, Greenawalt was a beloved teacher and colleague; his style on the page and in the classroom even inspired a new word: “Greenawaltiana.” He invited his students into his home to discuss legal concepts over tea and cookies or powdered donuts, milk, and cider, and his impact was felt across generations: Paul Horwitz ’97 LL.M., a University of Alabama School of Law professor who studied under Greenawalt, said he tries to emulate Greenawalt in his own courses; Oriane (Hakkila) Green ’17, an associate at Clifford Chance in New York, said Greenawalt was one of her most influential professors.

In her tribute to Greenawalt on his half-century on the Law School faculty, Dean Emerita Barbara Aronstein Black ’55, who was dean when Greenawalt became a University Professor in 1991, wrote that he was “mighty close” to being “indispensable” to Columbia Law School. She and others noted his constant willingness to offer feedback and commentary on his colleagues’ work, which often resulted in improved arguments.

“Kent is always willing to engage in scholarly dialogue, and has had much opportunity to do so, because the excellence and power of his work has commanded so much attention,” she wrote. “When he speaks, everyone listens.”

Greenawalt was born in Brooklyn on June 25, 1936, but grew up in Hartsdale, New York, attending Edgemont and Scarsdale high schools. His father, Kenneth W. Greenawalt, was a trial lawyer who practiced in the areas that Greenawalt later studied; in 1965, the elder Greenawalt successfully defended three men who refused to join the U.S. Army on religious grounds. Greenawalt’s mother, Martha Sloan Greenawalt, who earned a master’s degree in philosophy from Columbia in 1929, served on the League of Women Voters’ national board and as a local coordinator for the Equal Rights Amendment Coalition.

“During my youth, I took it for granted that one’s religious commitments and understandings would matter for one’s life, including one’s life as a citizen, and that liberal democracy was a system of governance that warranted support,” Greenawalt wrote in Religious Convictions.

Greenawalt graduated from Swarthmore College in 1958 and then studied at Oxford for two years, earning a bachelor of philosophy degree in politics. At Columbia Law School, he was a James Kent Scholar and editor in chief of the Columbia Law Review. He later clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan and then spent a year working at the U.S. Agency for International Development in Washington, D.C. He also worked as an attorney for the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in Jackson, Mississippi.

In 1965, Greenawalt returned to Manhattan and his law school alma mater, joining Columbia Law as an assistant professor. He left in 1971 for a brief stint to serve as deputy solicitor general, where he worked with first assistant to the solicitor general Daniel M. Friedman ’40; soon after returning to the Law School, he was named Benjamin Nathan Cardozo Professor of Jurisprudence.

Greenawalt was a prolific writer, churning out books at an astounding rate. In addition to Religious Convictions and Speech, Crime, and the Uses of Language, other notable works include Fighting Words: Individuals, Communities, and Liberties of Speech and Does God Belong in Public Schools? (In the latter, he argued students should learn more about religion, especially in a historical context.)

Between 2015 and 2018, Greenawalt published a book every year, including Interpreting the Constitution; Exemptions: Necessary, Justified, or Misguided?, which addressed the use of religious exemptions from legal obligations; When Free Exercise and Nonestablishment Conflict, about the First Amendment’s religious provisions; and Realms of Legal Interpretation: Core Elements and Critical Variations, which offered a summary of judicial decision-making and a guide to how judges could more uniformly approach public and private law controversies.

Speaking in 2015, Greenawalt said he “deeply appreciated” his time at Columbia Law School. “I feel it has been a truly fortunate way to spend my life,” he said.

Outside the classroom, Greenawalt was active in the bar, especially early in his career. From 1966 to 1969, he served on the civil rights committee of the New York City Bar Association; the following two years, he was a member of the due process committee of the American Civil Liberties Union. He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society and, from 1991 to 1993, president of the American Society for Political and Legal Philosophy. In addition, he was named a fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies; Clare Hall, University of Cambridge; All Souls College, University of Oxford; and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He is survived by his three sons, Alexander K.A. Greenawalt ’00, Andrei Greenawalt, and Robert M. Greenawalt ’02, and his stepchildren, David Pagels and Sarah Marie Toussaint.