Release and Reentry

How can the formerly incarcerated make a new life?

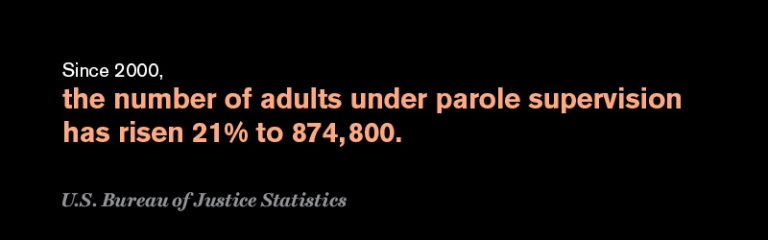

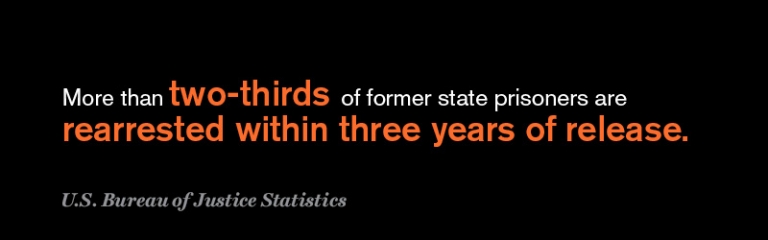

As the prison population has soared since 1990, so has the number of people released: In 2016, nearly 875,000 people were under parole supervision in the United States, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Reentry programs aim to reduce the high rate of recidivism, but the difficulty, Professor Susan Sturm says, is matching the scale of the programs to the need.

“There is very good data about what works to help formerly incarcerated people transition to living in the community,” Sturm says. “How you implement programs at a systemic level—that can have the impact on the programmatic level—is something that we don’t have answers to.’’

Some federal funding is available for reentry programs to help formerly incarcerated people find jobs, housing, and health care. The First Step Act of 2018, for instance, provides $375 million over five years for reentry programs, though it has not yet been fully funded.

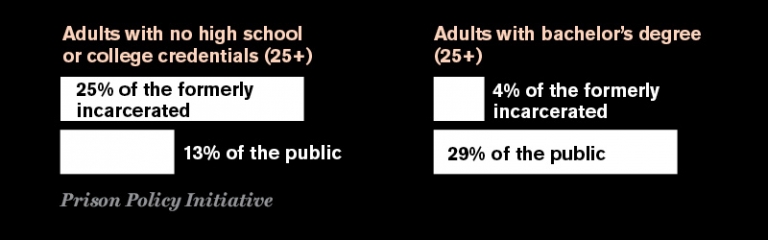

Sturm’s work has focused on access to education because it is “one of the most important ways” of preventing recidivism. Only half of adults in prison have a high school diploma or an equivalent, according to BJS statistics. The Center for Institutional and Social Change, which Sturm directs, teamed with Hostos Community College in New York City to identify the barriers keeping formerly incarcerated people out of education programs.

Columbia Law Professor Philip Genty, an expert in prisoners’ rights and family law, is designing a new clinic for Columbia Law students that will focus on remedies for “collateral consequences” of incarceration, such as the ability to seal a conviction or win back a work-related license.

Genty wants to find ways for formerly incarcerated people to build on skills they learned in prison, whether it is pro se legal research or peer mentoring. A program to help a jailhouse lawyer become a paralegal, for instance, would provide not only a good job but also the ability to help other formerly incarcerated people. “Part of what works, I think, is bringing people together who have experiences from inside the prison,” Genty says, “not only to support each other but also to build on each other’s strengths.”

“Recidivism is often linked to financial insecurity, and finding work after incarceration is difficult. Helping individuals develop skills to build their own businesses offers them a route to a more secure and stable future.” —Meg Gould ’21, who is co-developing a program to help formerly incarcerated people become certified paralegals