Power Struggles in a Partisan Era

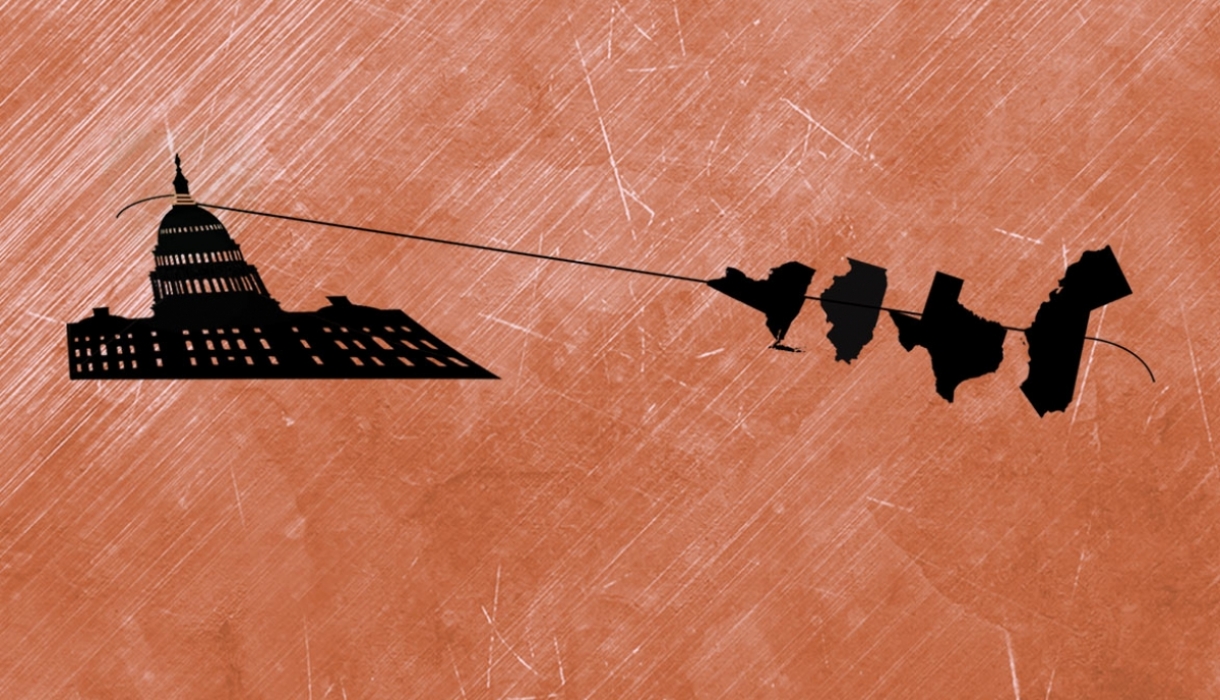

Standoffs between states and the federal government, and states and cities, are increasingly common. Columbia Law professors examine the impact and propose solutions.

By Martha T. Moore

When St. Louis raised the minimum wage to $10 an hour, it immediately came under attack from the majority-Republican state legislature. After the city successfully defended its law in the Missouri Supreme Court, state legislators passed a law forbidding any locality from setting a minimum wage higher than the state’s. And so, in August 2017, four months after the new St. Louis wage went into effect, it fell back to the statewide $7.70.

Since 2015, state legislatures have passed dozens of similar so-called preemption laws that overrule local ordinances: More than half the states forbid local regulation of the minimum wage, 23 states prohibit local requirements for paid sick leave, and eight states block local bans on plastic bags.

These ideological fights—now under scrutiny by several Columbia Law professors—are a result of a divergence in political control: State governments are often dominated by Republicans, while a majority of big cities are led by Democrats. State legislatures “have become more ideological, and they just don’t like the policies that the local governments in their states have been advancing,’’ says Richard Briffault, the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation. Such actions have prompted Briffault to argue that local authority needs greater legal protection.

Multiple Power Struggles

Although the present hyperpartisan era seems unprecedented, Professors Jessica Bulman-Pozen and Gillian E. Metzger ’96 explore similar power struggles between the states and the federal government dating back to the New Deal.

States are currently at the forefront of policymaking on many topics because partisan gridlock in Congress has effectively prevented federal action, says Bulman-Pozen, a faculty director of the Center for Constitutional Governance. Voters are, in effect, looking to their state government to represent their values the way they traditionally turned to the federal government.

“It’s really hard to get [legislation] out of Congress both because there’s disagreement on the substance and because there’s general tribalism and animosity that colors even noncontroversial kinds of bills,’’ Bulman-Pozen says. “That dynamic at the state level looks really different. You see really polarized parties, but you see California being deep blue, Texas being pretty red. So they’re actually able to make policy even though they’re no less polarized.’’

Since one party is always out of power in the White House, she points out, states controlled by the out-of-power party provide checks and balances to the federal executive: They either contest federal action, or they implement their own policies. Colorado legalized marijuana, Arizona passed strict anti-immigration laws, and California enacted net neutrality—all despite federal policy to the contrary.

The Risks of Regionalism and Preemption

Today’s regionalism is defined more by partisanship than geography, Bulman-Pozen says. In “regionalism without regions,’’ states take joint action on the basis of shared policy goals rather than geographical proximity. A group of blue states including California, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, for instance, has adopted greenhouse gas–reduction goals to combat climate change.

So far, Bulman-Pozen sees alliances as fairly positive. “Allowing for some kind of state-level policymaking is a necessary safety valve in the system,’’ she says. “The fact that people can channel their political energy, their political commitments, their attempts to make change in actual policies, to actual governments . . . is salutary.’’

On the other hand, such alliances, can intensify the nationwide partisan divide over policy, she notes. Bypassing the need to hammer out a single policy solution and heightening differences between states could exacerbate national polarization.

Additionally, with power struggles also intense on the state and local levels, Briffault worries that a surge in preemption leaves local governments unprotected. In particular, he points to what he calls “punitive preemption” laws, such as those passed by Florida, Texas, and Arizona, that include personal liability for local elected officials who don’t cooperate and financial penalties for localities.

In Texas, a 2017 law forbidding sanctuary cities requires local officials to enforce immigration law or face fines and jail. In Florida, local officials who pass gun-related ordinances can be liable for $5,000 fines and removed from office. Some states, including Texas and Oklahoma, have considered bills restricting the legislative powers of municipalities so tightly that Briffault terms them “nuclear preemption.’’

In the past, Briffault considered himself a “local-government skeptic,’’ concerned that parochial concerns inhibited good policy decisions on the municipal level. Local land use laws, for instance, have been contributors to sprawl and the scarcity of affordable housing. “No one is always the good guy,’’ he says. But now, he points out, parochialism is less the problem as localities set policy on what could be considered national issues, such as gun safety, workplace equity, public health, and environmental regulation.

Civil Rights at Stake

In 2016, when Professor Olatunde Johnson, the Jerome B. Sherman Professor of Law, examined recent civil rights legislation on the state and local level, she was heartened by one trend: In the absence of federal legislation, 19 states and 185 cities and counties outlawed discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. States and cities prohibited discrimination in housing against federal voucher recipients and enacted “ban the box” laws that regulate consideration of criminal history in employment applications.

But after the 2016 election, Johnson, a faculty director at the Center for Constitutional Governance (CCG), noticed that these measures, too, had become mired in power struggles, as Republican-dominated state legislatures preempted local laws addressing, among other subjects, discrimination and labor conditions. North Carolina’s 2016 “bathroom bill,’’ for instance, prevented municipalities from allowing transgender people to use the public bathroom of their choice. (A 2017 partial repeal of the law ends the ban on municipal action in 2020.)

Local and state laws that require paid sick leave and raise minimum wages “reflect the understanding that just banning discrimination isn’t enough to make people included in our economies,’’ Johnson says. And while federal legislation has traditionally been advocates’ vehicle for civil rights, the current congressional gridlock makes a focus on state and local measures sensible.

Beyond Anti-Administrativism

Small-government conservatives, including conservative Supreme Court justices, today make the same arguments against the spread of the federal government that their New Deal-era predecessors did, Metzger notes in her Harvard Law Review foreword, “1930s Redux: The Administrative State Under Siege.” They decry the “administrative state,’’ the array of federal executive agencies with regulatory, adjudicatory, and enforcement functions, as a violation of the separation of powers.

Metzger, also a faculty director of CCG and the Stanley H. Fuld Professor of Law, argues that the opposition to administrative powers is outdated and unrealistic, and it threatens to further politicize the Supreme Court. Instead, broad delegations of authority to the executive branch agencies represent the central reality of contemporary national government.

Separation of powers analysis should focus on the government as it exists. “It’s one thing to say that the administrative state is constitutional. It’s another to say we couldn’t think of some pretty important reforms,’’ Metzger says. For instance, federal agencies with administrative law judges, like the Securities and Exchange Commission, can be perceived as having a “home court advantage’’ in judicial proceedings, she says. Although empirical work has rejected such claims, reforms that help counter perceptions of bias are still worth considering to ensure administrative adjudication is seen as legitimate.

Legal Defenses

On the state level, partisan-driven preemption is so new that Briffault, Johnson, and other scholars are working with the Local Solutions Support Center to educate city and county governments about the increase in preemption legislation by state governments and how it could be challenged.

The group includes a dozen law professors and nonprofit lawyers and law student researchers. It shares information and resources online for preemption cases, and Briffault has done a “road show’’ at gatherings of city and county attorneys. In January 2019 he and other scholars will publish a reader of statutes, court cases, and commentary dealing with the current surge in state preemption.

Challenges to preemption have few established legal arguments, Briffault says. The federal constitution doesn’t mention local government. The concept of “home rule,” included in most state constitutions, is designed to allow localities to make laws, but generally does not protect them from state preemption. Local authority needs greater protection in the courts because it embodies the values of federalism—sensitivity to diverse needs, greater citizen involvement, and the ability to innovate and experiment. “These values should be reflected in our legal principles,’’ he says. “For me, it’s less about the substance of these laws and more about the idea that [cities] should be free to experiment.’’

In the Classroom

With the help of Professors Bulman-Pozen, Metzger, and Johnson, who co-teach a Constitutional Governance Practicum, students gain experience confronting governmental power struggles. Now in its second year, the practicum allows students to combine theory with hands-on learning. “We wanted to create a classroom opportunity that combines a classic seminar with a deep intellectual dive into a topic—federalism—and a more clinical experience where students can apply what they are learning about the law directly and be involved with litigation and drafting,’’ Bulman-Pozen says.

In last year’s class, students helped prepare an ACLU challenge to a Texas law that required local law enforcement to cooperate with federal immigration agents. They also addressed constitutional questions about state preemption of local minimum-wage ordinances, a federal bill that would require states to recognize other states’ concealed-carry permits for firearms, and more.

Though the practicum is designed to enhances students’ experience, the faculty find that the learning goes both ways. In fact, an article Bulman-Pozen drafted based in part on the practicum’s work was recently cited by a federal court in a case about New York City’s “sanctuary” policies. “It’s a great opportunity for the students,” Bulman-Pozen says, “but it’s also nice for the three of us to actually get to engage very immediately with active litigation and active legislative drafting.”

Work by Faculty Members

For additional, in-depth insights on federalism and preemption from these faculty members, continue reading their original essays below.

The Challenge of the New Preemption, by Richard Briffault

Our Regionalism, by Jessica Bulman-Pozen

Preemption and Commandeering Without Congress, by Jessica Bulman-Pozen

The Local Turn; Innovation and Diffusion in Civil Rights Law, by Olatunde C. Johnson

The Supreme Court, 2016 Term: Foreword: 1930s Redux: The Administrative State Under Siege, by Gillian E. Metzger

Federalism Under Obama, by Gillian E. Metzger

Martha T. Moore is a former national and political reporter for USA Today and was a Knight-Bagehot fellow in economics and business journalism at Columbia Journalism School.