Professor Thomas Merrill on the Legal History of Chicago’s Magnificent Lakefront

In his new book, Lakefront, Merrill traces how lawsuits, court rulings, and political machinations from the 1850s to the present have resulted in an urban coastline that’s the pride of Chicago and the envy of other cities.

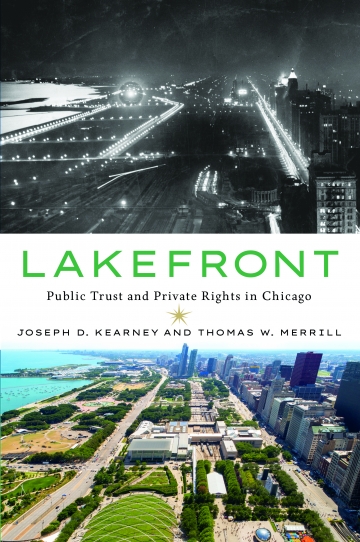

Litigators, politicians, judges, and self-interested citizens—not urban planners or landscape architects—are the heroes of Columbia Law School Professor Thomas W. Merrill’s new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press). Merrill and his co-author, Joseph D. Kearney, dean of Marquette University Law School, have written a compelling history that details the origins of the public trust doctrine and how legal maneuvers shaped the city’s breathtaking 26-mile coast with its string of parks, beaches, museums, marinas, and other public amenities such as a zoo, a football stadium, and a glittering outdoor amphitheater designed by architect Frank Gehry.

Merrill, Charles Evans Hughes Professor of Law, has deep ties to Chicago. Before moving to New York and joining the Columbia Law faculty in 2003, he was a professor of law at Northwestern University, practiced law at Sidley & Austin in Chicago, and earned a J.D. from the University of Chicago Law School. (He also lived in Washington, D.C., when he clerked for Chief Judge David Bazelon of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and for Justice Harry Blackmun of the U.S. Supreme Court and when he served as deputy solicitor general in the U.S. Department of Justice, from 1987 to 1990.)

Merrill’s fascination with Chicago’s shore dates back to his law school days in the mid-1970s. “My first-year property professor told stories about the lakefront that captured my imagination,” he says. “Later, when I started teaching property at Northwestern, I reread that professor’s article on the lakefront, and it didn’t add up—the legal and narrative pieces did not synchronize very well. I thought it was a giant jigsaw puzzle that needed to be resolved and a perfect challenge for somebody interested in both legal history and property.”

Public Trust

The lakefront was far from a greensward in 1852 when the city of Chicago passed an ordinance allowing the Illinois Central Railroad to build tracks on landfill and pilings in Lake Michigan. In 1869, the Illinois legislature passed The Lake Front Act, in which the state gave the railroad permission to construct a new outer harbor in the lake, which became known as The Lake Front Steal. But in 1873, the legislature repealed the act as a rebuke to the railroad for a variety of misdeeds, returning control of the lakefront to the city and state. The railroad argued in Illinois Central Railroad Company v. Illinois that the state was violating the U.S. Constitution’s contract clause by nullifying their agreement, leading to a showdown in 1892 at the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in the state’s favor.

“Doctrinally speaking, the railroad had a very strong case,” says Merrill. “But the justices were sympathetic to the state’s desire to prevent a private corporation from dominating the lakefront and needed some justification for siding with it. Justice Stephen Field came up with the ‘public trust doctrine,’ which basically said that the land granted to the railroad was held in public trust and therefore can never be granted away to a private corporation in a fashion that would potentially deprive the public of access to the resource.”

The doctrine was based upon a common law concept that traditionally focused on the public’s right to access navigable waterways and to engage in activities like shellfishing in submerged lands. “The public trust doctrine has become very interesting to property law because it’s one of the only doctrines that suggests that there are certain resources that you cannot privatize,” says Merrill. “It has a sort of magnetic attraction for environmentalists and their advocates who would like to put certain resources off limits from economic or private property development.”

Since the 1970s, there have been debates about whether the public trust doctrine can be applied to protect wildlife, the atmosphere, and intellectual property. “It’s quite an interesting doctrine in the sense that it runs counter to the main thrust of American law, which is to encourage private property rights and protect against government interference,” says Merrill.

“The public trust doctrine has become very interesting to property law because it’s one of the only doctrines that suggests that there are certain resources that you cannot privatize.”

Public Dedication

One of the hallmarks of the Chicago lakefront is its world-class museums, including the Adler Planetarium, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Field Museum, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the Shedd Aquarium. But the Art Institute is the only one located in the 319-acre Grant Park. Merrill notes that the reason no other buildings were erected in this central location has much to do with lawsuits filed between 1890 and 1910 by mail-order-catalog magnate Montgomery Ward, who owned property across the street. Ward did not want to see more development in the park, so he invoked the “public dedication doctrine,” which holds that owners of private property abutting land dedicated to a public use have “a right to enjoin deviations from the dedication.” The precedents set by the Ward cases kept Grant Park free of significant encroachments for more than a century.

“The book is pretty sympathetic to the public dedication doctrine,” says Merrill, noting that a self-interested citizen’s concerns can ultimately benefit the greater good. “There seems to have been an unending stream of ideas for big things to build in Grant Park, including more museums, a library, and a new city hall, and all these projects were nixed because of the public dedication doctrine leaving the space widely open.”

Megastar Wars

In the past few years, there have been major fights over erecting two new museums along the lakefront in the area south of Grant Park. The billionaire Star Wars director George Lucas proposed building his privately funded Lucas Museum of Narrative Art on a parking lot near the Soldier Field football stadium, which was endorsed by the Chicago Park District, the mayor, and the state legislature; but the nonprofit Friends of the Parks went to federal court to enjoin the project citing the public trust doctrine. Before the litigation could be resolved, Lucas got fed up with the legal wranglings (and criticism of the museum’s design), abandoned Chicago, and is now building the museum in Los Angeles.

The battle between politicians and planners, who are concerned with creating jobs and additional tax revenue, versus the preservationists, who want to maintain open space, is ongoing with neither side able to claim the moral high ground. “The Lucas Museum episode epitomizes the predominant version of today’s disputes over the fate of lakefront,” write Merrill and Kearney. “Both sides claimed to represent the public.”

Similarly, the Obama Foundation’s plans to build the Obama Presidential Center in the South Side’s Jackson Park—originally designed by Frederick Law Olmstead and the site of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—has been the subject of two lawsuits. A group called Protect Our Parks challenged the city’s right to transfer the use of public parkland to a private foundation under the public trust doctrine. In April, the Supreme Court denied the group’s request to review a lower court’s ruling that the group lacked standing to sue the city in federal court over the use of the parkland. Now, another federal suit by Protect Our Parks charges the presidential center has not gone through the proper environmental impact reviews.

Be Careful What You Wish For

The advocacy group Preservation Chicago has floated the idea of turning the lakefront into a national park, which would likely maintain the status quo and keep development at bay. But in a recent op-ed in the Chicago Tribune, Merrill and Kearney argue that such a move was probably not in the best interest of the city and its 2.7 million residents. They note that some national parks charge admission, and they explain that both the public trust doctrine and public dedication doctrine are state law and would not apply if the federal government took over. The future of the lakefront, they contend, should be decided by Chicagoans themselves.

“Serious thought should be given to the democratic implications of turning Chicago’s most treasured asset over to a Washington bureaucracy,” they write. “The people have argued, protested, finagled, and sued and, in the end, created the most spectacular waterfront in the nation, perhaps the world. . . . Chicagoans should think long and hard before putting the lakefront’s fate into someone else’s hands.”