Portrait of an Art Lawyer

Gert Jan van den Bergh ’91 LL.M. seeks justice for artworks and their owners.

In Gert Jan van den Bergh’s law practice, the cases are as narrow as a single brushstroke and as broad as the canvas of world history.

Van den Bergh is an expert in art restitution, a field of international law that emerged from the devastation of World War II and which has grown to encompass the repatriation of artifacts to formerly colonized nations.

“What is so interesting about this practice is that you’re at the crossroads of history, legal practice, and very personal stories of families,” van den Bergh says. “They’re often feature-picture worthy because they’re highly personal and very interesting.”

Van den Bergh practiced intellectual property law in Amsterdam, his hometown, until 2004, when his career changed direction after he was introduced to Marina Mahler, granddaughter of the composer Gustav Mahler.

In 1938, the composer’s widow, Alma, and her third husband, the Jewish writer Franz Werfel, were forced to flee Vienna after the Nazi invasion. They left behind their art collection, including the Edvard Munch painting Summer Night on the Beach, which was on loan at the time to the Austrian national gallery. Alma’s Nazi step-family looted most of her belongings and, without her knowledge or permission, sold her beloved Munch for a pittance to the Austrian gallery. Alma spent the rest of her life trying to get the painting back, without success.

Van den Bergh took on the Mahler case, and in 2006, on the family’s third attempt to reclaim the painting and five years after Austria joined a multinational agreement on art restitution, was finally able to get the painting returned to the family. The victory came a few months after the same museum had returned five Gustav Klimt paintings, including Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, to Maria Altmann, Bloch-Bauer’s niece—a case that formed the basis of the movie Woman in Gold. Mahler’s Munch is now in the Museum Barberini, in Potsdam, Germany; Altmann sold the Klimt portrait to the Neue Galerie New York.

A Welcome Specialty

At the time, van den Bergh had just launched his own firm, Bergh Stoop and Sanders, after more than 20 years at the Amsterdam-based firm Stibbe. He had practiced intellectual property law since earning his LL.M. at Columbia in 1991, studying with Jane C. Ginsburg, now Morton L. Janklow Professor of Literary and Artistic Property Law, and the late John M. Kernochan.

“What I like about the law practice is the combination of academics and practicalities. I like to write. I like to delve into the specifics of a factory, a client, a business,” van den Bergh says. “I’m a curious person, and I’m very committed. At the same time, I have professional detachment, and I’m easily bored. So once I get bored, there are always a ton of other files for me to be busy with.”

With the successful conclusion of the Mahler case, van den Bergh became a restitution specialist. “I have always been interested in art. I’m a collector, and I’m a pianist,” he says. “Whenever you do something that truly includes your passion, then that will very much enhance the quality of your output. This mixture of art and law for me is basically a dream come true.”

The issue of returning Nazi-looted art remains acute in the Netherlands, where three-quarters of the country’s Jews were killed by the Nazis, more than in any other country in Europe. “The burden is so much greater,” van den Bergh says. Of an estimated 600,000 works of art looted by the Nazis in Western Europe, 100,000 are still missing.

In 2013, after more than 200 artworks from Dutch museums were returned to the descendants of art dealer Jacques Goudstikker (in a case litigated by New York art restitution expert Howard N. Spiegler ’74), the Dutch art restitution panel began using a “balance of interests” test that allowed museums to assert that an artwork was too important to the institution to give up. In December, a government-convened committee of experts urged an end to the test, days after a court refused to overturn the panel’s decision not to return a disputed Kandinsky in an Amsterdam museum because it was “essential” to the museum’s collection.

“I am pleased, yet there is still so much more to be done,” van den Bergh says. “We have entered into somewhat of a litigious atmosphere—us against them, the claimants against the museums—whereas I always say, ‘We’re in this together.’ We’re in the truth-finding process aimed at the healing of historical wounds.”

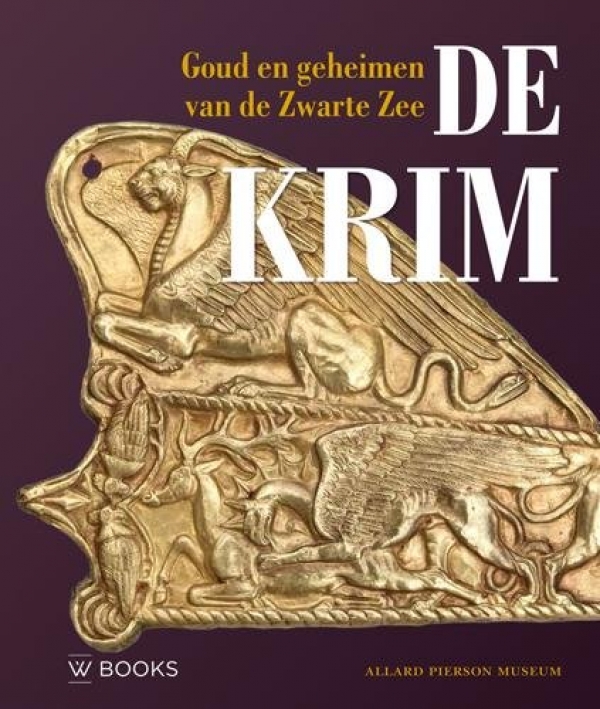

Finding Art’s True Home

Van den Bergh is currently representing the Ukrainian government in its dispute with four museums in Russian-occupied Crimea over a collection of Scythian gold and other archaeological objects loaned in 2014 to an Amsterdam museum. A month after the exhibit opened, Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula. Returning the collection to the museums, rather than to the national museum in Kiev, would be handing over Ukrainian cultural heritage to Russia, van den Bergh says. A lower court agreed and said that a Ukrainian court should decide whether the objects belong in Kiev or Crimea. The case has been appealed, and a decision is expected in September.

“If you look at the exhibit catalog that was given to the public, on page one it says, ‘These artworks tell you something about the Ukrainian identity,’” van den Bergh says. “Why would that have changed after the annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russian Federation?”

The Ukraine case is a modern version of an old problem that is increasingly confronting the Netherlands and other European countries: the repatriation of art and artifacts taken from former colonies. For countries such as Indonesia, which the Netherlands controlled until 1945, the issue of repatriating cultural artifacts is “an open wound,” van den Bergh says. Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum holds about 4,000 colonial objects, including the 36-carat Banjarmasin diamond, and some “were quite clearly flat-out looted.”

While the Netherlands and other European countries have established policies for returning artifacts, the process has been extremely slow. Museums are reluctant to part with objects in their collections. But van den Bergh sees repatriation as an opportunity for museums to grow.

“For some museums, it’s terrifying. At the same time, it’s a great opportunity to do the right thing,” he says.

Artifacts that might be returned to former colonies make up a small percentage of European museums’ holdings, he says. “The idea of empty museums is ludicrous.” Instead, museums have a “social, humanitarian, even to a certain extent a political obligation towards the key players and not only towards the visitors but the public at large.

“Museums can be an active party in a historical revisiting of attitudes of colonialism, restitution of national identity to African and Asian former colonies as a measure to show respect, and building bridges between nations that have a fraught historical relationship. It’s not just about ownership of these particular artworks. It’s part of a much grander discussion,” he says. “Things are shifting right now, and I think it’s all intertwined. From that perspective, we live in a very interesting time.”