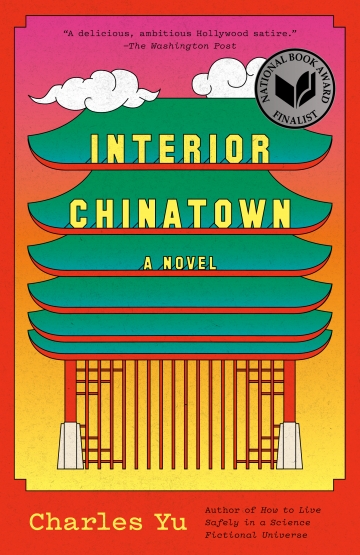

National Book Award Finalist Charles Yu ’01 Skewers Asian Typecasting On and Off Screen

His novel Interior Chinatown tackles issues of Asian American identity in culture and law.

Update: Interior Chinatown officially won the National Book Award for fiction on November 18, 2020.

Yes, a dramatic courtroom scene serves as the denouement of Interior Chinatown, the National Book Award finalist written by Charles Yu ’01. He wrote the novel in the form of a screenplay satirizing a cop show, and as everyone knows, Law and Order always ends with a trial.

But Yu spent 13 years practicing corporate law before turning to writing full time, and the courtroom scene also serves the novel’s deeper purpose: to foreground the Asian American experience of being sidelined culturally and legally—or as the lawyer defending Willis Wu, the novel’s hero, puts it, “two hundred years of being perpetual foreigners.” His Exhibit A is a list of punitive legal measures beginning with an 1859 Oregon constitutional amendment forbidding property ownership by Chinese people up to the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, a federal law prohibiting all immigration from Asia.

“Having no real political or social status or power, [Asian immigrants] could only really look to the legal system,” Yu says. “Alongside and in parallel with Blacks and Latinos, they were able to very slowly and, I think, painfully advance the ball forward in terms of civil rights.”

The novel’s screenplay is for a show that pairs a Black male cop and a white female cop and seemingly has little space for an Asian American character that isn’t the dead body. Willis Wu struggles to upgrade his roles in the fictitious cop show’s episodes from “Generic Asian Guy” to “Delivery Guy” to “Kung Fu Guy,” the pinnacle for an Asian actor. Despite some successes, he retains the feeling of being marginalized. “Someday you want the light to hit your face just right,” Wu says.

Yu’s book—his fourth—is partly a send-up of the industry he’s been working in since 2014, when he left a job as associate general counsel for Belkin International to write for the HBO show Westworld. (He has also written for and produced Legion and Sorry For Your Loss.) But the novel’s points about the backgrounding of Asian Americans also have considerable relevance to his experience in the legal world where, he says, Asian American lawyers are rare and often perceived as diligent but never stars: “A good number two. You know, a solid lieutenant.”

Asian American lawyers suffer from the “model minority myth,” which characterizes them as uniformly competent, hard working, and docile, Yu says. “And some of it just comes from the fact that even as Asian Americans have made inroads into the legal field in the last few decades, it still very much feels like another professional field that Asians can do well at, but not get to the very highest levels.”

Yu’s parents immigrated from Taiwan before he was born. “If you’re an Asian American—either an immigrant or offspring of immigrants—what are the acceptable things? How do you try to get some status here?” he says. For Yu—who grew up in California and went to University of California, Berkeley—that thing was attending Columbia Law School. “It was a big deal, going to Columbia,” Yu says. “All of a sudden, it made me feel, rightly or wrongly, like people took me more seriously.”

Yu chose Columbia Law because “I wanted to live in New York, and I knew Columbia was a really great school,” he says. “I figured I would be exposed to people and ideas and faculty that I just wouldn’t get to ever experience [otherwise]. And it was true: I got to see professors lecture who are literally at the top of their field . . . [and] love what they do.”

That example of passion for one’s work has stayed with him, Yu says. So has the discipline of legal training. “Being taught how to think like a lawyer gave me an attention to precision in language and in thought that’s really helpful,” he says. His years of practice—at law firms including Sullivan & Cromwell LLP and in-house at tech companies—gave him the “mental stamina” to endure marathon scriptwriting sessions. “I’ve found that I can handle long hours, maybe better than some TV writers,” he says. “When people are exhausted and can only think about ordering in dinner, I’m like, ‘Oh, this is when lawyers start the second part of their day.’”

Interior Chinatown was published in January; the advent of the coronavirus and the Black Lives Matter resurgence has made its themes even more resonant. President Trump’s characterization of COVID-19 as the “China virus” has “weaponized that perception of Asians as perpetual foreigners,” Yu says.

Despite the chaotic times, “it does for the first time in a long time feel like there are conversations happening that wouldn’t otherwise be happening. And if at some point that also provides a good entry to talk about discrimination against Asian Americans, that’s also a hopeful development,” Yu says. “If there is a larger idea to the book, it’s that a distorted picture of race in America hurts all groups, not just Asians.”