Kathryn Judge Has a Vision for Shorter Supply Chains and a More Humane Economy

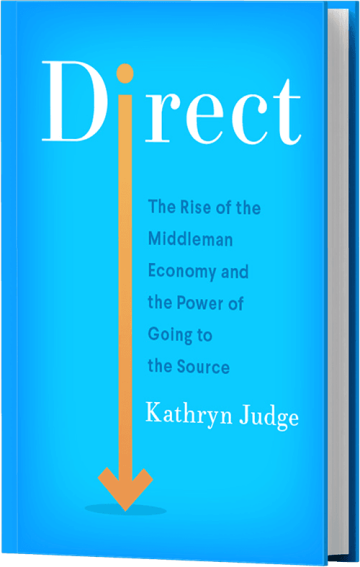

In her new book, Direct: The Rise of the Middleman Economy and the Power of Going to the Source, the Columbia Law professor weaves together her expertise in financial regulation and her experiences as a conscientious yet conflicted consumer.

Kathryn Judge, Harvey J. Goldschmid Professor of Law, teaches courses on financial regulation, corporations, and law and economics at Columbia Law School. She focuses her scholarship on financial markets and regulatory architecture, and she serves on the editorial boards of the CLS Blue Sky Blog and the Journal of Financial Regulation. But it’s Judge’s experiences as an ordinary consumer and mother of two school-age daughters that provide relatable anecdotes and emotional resonance for her new book, Direct: The Rise of the Middleman Economy and the Power of Going to the Source (Harper Business).

“The book takes ideas from the academic work I’ve done trying to understand what went wrong with the financial system in 2008 and draws on my life as much as anything to bring those ideas to life,” says Judge.

In the preface, Judge shares the story of when her second daughter, who was born with “an unusual heart,” had to undergo open-heart surgery when she was 1 week old and again 10 months later. By happenstance, Judge found what she describes as “unexpected kinship” with a family in northern Canada, whose infant had a similarly unusual heart, when she saw their appeal on GoFundMe, the online platform that allows people to ask friends, family, and strangers to support a dream or a challenge.

Judge’s modest GoFundMe donations to several families in similar situations—and her meaningful email exchanges with them—led to an aha moment: Her scholarly mind recognized how “direct exchange and platforms designed to encourage connection and communication can transform an exchange into an opportunity to forge new bonds, enjoy experiences we could never purchase in isolation, and see firsthand the impact of our actions on others,” she writes.

Direct exchange is the antithesis of the “middleman economy,” which is characterized by powerful middlemen (e.g., Amazon and Home Depot) and long supply chains. In Direct, Judge dissects the benefits and dangers of this dynamic and how it connects but also separates us. The book is a call for people to seek out some direct exchange when they can—purchasing goods and securing services closer to their source, rather than through intermediaries—and thereby reduce the complexity of today’s supply chains and the power of the largest middlemen. “It’s about a rebalancing,” says Judge, who writes that “the very different ecosystem that grows out of direct exchange—between makers and consumers, investors and entrepreneurs . . . shows how much is at stake in the threshold issue of ‘through whom’ we buy, invest, and even give.”

Uncovering Patterns

In researching the 2008 financial crisis, Judge observed how traditional relationship-oriented banking had given way to a system where large banks functioned as the main intermediaries and how their reliance on data and standardization in turn contributed to the growth of long capital supply chains via innovations like securitization. “The combination was transformative in terms of how finance actually operated,” she says. “It left us much more disconnected and then created this opacity and fragility which, in turn, created a lack of accountability in the financial world.”

As she looked beyond the world of finance to her own consumer habits (inspired by a fateful, out-of-character shopping spree at Walmart), Judge saw global behemoths such as Walmart, Cargill, and Nestlé in a new light as middlemen with outsize power and monopolistic market shares. These companies, she notes, lure customers with convenience and low prices, but their cost-cutting often has severe consequences, particularly in terms of environmental impact, worker exploitation, and quality control. “The process of allowing these large middlemen to play such a dominant role feeds into these long supply chains that were severely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and are exposed to geopolitical risk,” she says.

In Direct, Judge also explains how complex supply chains obscure the fact that we often buy clothing and food that are produced in ways we’d consider unethical if we knew about them.

She confesses her own misgivings about fueling her chocolate addiction with candy that may have been made with cocoa harvested by children and forced laborers in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. And she says that “fair-trade” cocoa “certified” by third-party middlemen, such as the Rainforest Alliance, is often merely virtue signaling for companies and gives the false impression that they care about the well-being of their essential workers.

One of the best ways Judge has found personally for direct exchange is as a member of the Genesis Farm CSA near her weekend home in Blairstown, New Jersey. Members of a CSA (community supported agriculture) pay a farmer up front for a season or two of fruits and vegetables without knowing exactly what or how much they will get each week, which often depends on the vagaries of the weather.

“I feel good about the money I pay to Genesis Farm each spring not just because of the delicious vegetables I anticipate getting but because I know the farm and farmers that my money is going to support,” she writes. But Judge is also a realist: She doesn’t think CSAs are a panacea and continues to shop through all sorts of middlemen. The concept of CSAs is a way for her to illustrate the range of ways we consume and how we are way too far from the source of so many things in our life.

The Middleman Markup

While mammoth corporations like Amazon are the most ubiquitous middlemen, Judge sheds light on others that squeeze consumers when, for instance, they are buying a car or a home. There are two common choices for auto loans: a bank or a car dealer. “Neither option is direct, but getting a loan from a lender cuts out one middleman—the car dealership—resulting in a shorter capital supply chain,” she explains. “Research shows that going directly to the lender tends to lead to lower financing costs for borrowers.”

Judge also offers a scathing critique of the National Association of Realtors and Multiple Listing Services, which have a stronghold on home buyers and sellers. “It’s an important example of how powers arise from being an intermediary and how we depend on them,” she says. While Judge allows that middlemen, such as real estate agents, build expertise and relationships that enable people to connect in ways they otherwise could not, she says that also gives them outsize power.

In the American residential real estate market, she notes, sellers usually pay a broker’s commission of 5% to 6% (compared with half that in many other countries), which eats into the nest egg of a median American family whose home is their number one source of wealth (compared with high-income households that accumulate much of their wealth in stocks and bonds). Because full-service brokers earn a fee based on the value of a house, “they are making more money as housing values skyrocket, but they’re not doing any more work,” she says. Judge believes the system can be tweaked so its benefits flow to the consumer with lower prices.

Change Begins at Home

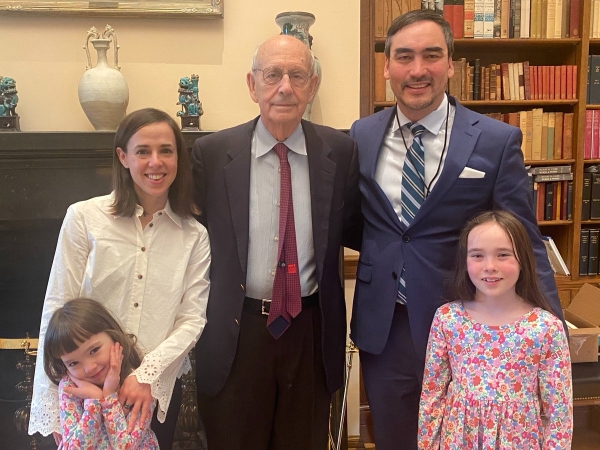

Judge shares her interest in consumer and antitrust issues with her husband, Tim Wu, Julius Silver Professor of Law, Science, and Technology, who is currently on leave from Columbia Law School as the special assistant to the president for technology and competition policy. (Judge and Wu also have in common their experience as law clerks—at different times—for both Judge Richard Posner of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit and Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Stephen Breyer.)

Judge arrived at Columbia Law School in 2009 after three years as a corporate associate at Latham & Watkins in San Francisco. She spent two years as an academic fellow developing a body of scholarship at the Law School’s Center for Law and Economic Studies and then joined the full-time faculty in 2011.

“I wanted to make the shift to academia because the 2008 crisis suddenly raised these really important and difficult questions, and no one had good answers. My entire focus on financial regulation was motivated by an appreciation of the ways that the crisis not only cratered the economy but disproportionately hurt the people who are most vulnerable,” she says. “It’s exciting to be an academic and be part of the overall effort by policymakers, by academics, by think tanks to understand how we got to this really bad place and to seek solutions.”

Judge ends her book with a host of policy suggestions and strategies for consumers to curtail the power of middlemen, but one of the simplest ways for most of us is to “buy direct at least some of the time.”

She is a fan of businesses like Etsy that support small makers and direct-to-consumer brands like Warby Parker (eyeglasses) and Allbirds (shoes), although none of these companies is perfect. She admires the online retailer Hanahana Beauty, a Chicago-based Black-owned business specializing in shea-based butters made by a women’s collective in Ghana. “Hanahana . . . embodies how direct exchange can transcend geographic and linguistic bounds to create new connections and move goods and money to where each is most needed without layers of middlemen,” she writes. “It also shows how disruptive and powerful a force that can be.”

Judge attributes great power to direct exchange by its “enabling connection, promoting community, counteracting the loneliness that remains so pervasive, and reworking hierarchies,” she concludes. “Direct exchange is not the right option all of the time, but it is a key ingredient to a balanced life and a healthier economy.”