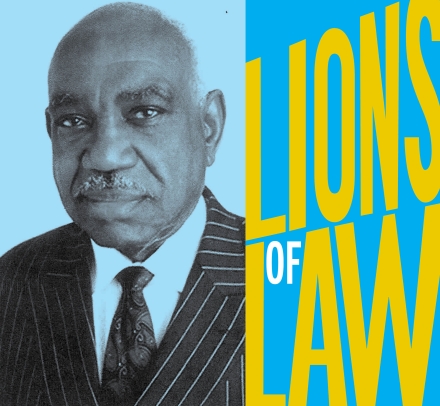

James Meredith ’68: A Racial Justice Pioneer

After risking his life to desegregate Ole Miss in 1962, Meredith continued his activism at Columbia Law School.

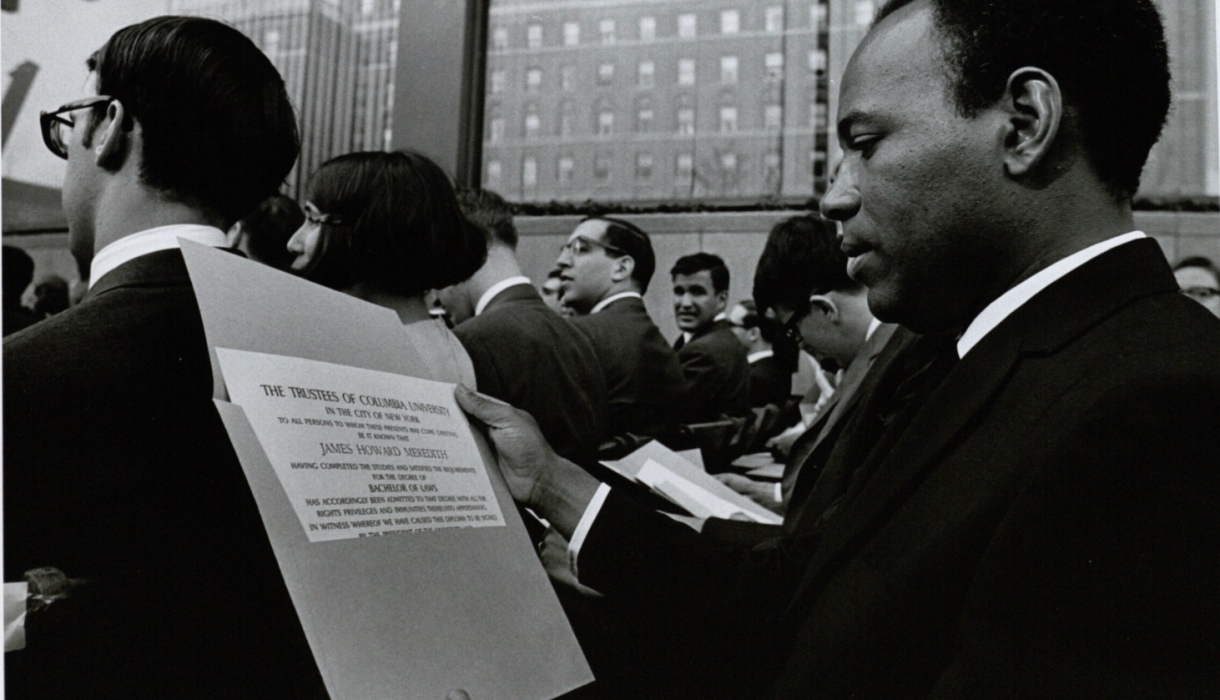

James Meredith ’68 is likely the only entering Columbia Law School student to have held a press conference on the day he registered for classes. His arrival on campus in September 1965 was covered by The New York Times.

The attention was well-earned: Three years earlier, Meredith’s enrollment as the first Black student at the University of Mississippi was a watershed moment for the civil rights movement in the United States. Martin Luther King Jr. called Meredith one of “the real heroes” in the fight against segregation in the South in his Letter From a Birmingham Jail. Meredith’s admission to Ole Miss followed a 16-month court battle led by Constance Baker Motley ’46 and required the backing of the U.S. Justice Department, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, and President John F. Kennedy. Tens of thousands of federal and National Guard troops were present on the day he reported to his first classes, and federal marshals protected Meredith around the clock until his graduation in 1963. (Meredith spent 10 months at Ole Miss; he had completed much of his undergraduate course work at Jackson State University, a historically black college, while fighting to get into Ole Miss.)

“Getting a degree from Ole Miss impacted my life more than any other single thing,” Meredith says in an interview from his home in Jackson, Mississippi. “Next to that, without a doubt, was a law degree from Columbia Law School.”

Columbia provided the legal training Meredith had always wanted: When he was growing up on a farm in Mississippi, lawyers and doctors were considered the most important people in the county, he recalled. And while he never planned to practice law, a legal education would further his plans to enter politics.

Meredith credits then-Dean William C. Warren with offering him a place at Columbia Law: Ivy League law schools had begun to recruit Black applicants, and Warren was determined to match, if not exceed, Harvard Law School’s efforts, Meredith recalls. Meredith was one of 10 Black graduates in the Class of 1968.

“Obviously, the dean had decided to give me a chance to be a leader for my people,” he says. Warren also met with Meredith to advise on course selection. The prominence of Columbia Law’s faculty impressed him. “In every class I had, the teacher wrote the book,” Meredith says. “[They] not only wrote the book for Columbia; the same book was being used all over America.”

Meredith’s time at Columbia Law was extraordinarily productive. By the time he received his degree in 1968, he had published a memoir, organized a voter registration march that drew thousands, survived an assassination attempt, and run for Congress. He spoke at rallies, wrote magazine articles, and appeared on Meet the Press with civil rights leaders including Stokely Carmichael and King.

For many of his classmates, Meredith was a hero.

“Everybody was kind of excited and proud,” says Robert Smith ’68, who was editor of the Columbia Law Review in 1968 and an associate judge of the New York State Court of Appeals. “This was somebody who had done something more meaningful in his life than any of us would ever do.”

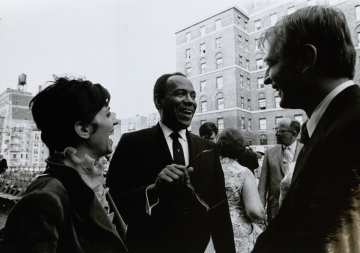

As a teenager in Greensboro, North Carolina, Waldo C. Falkener Jr. ʼ68 had witnessed the first lunch counter sit-ins. He recalls the cocktail party thrown by Dean Warren for incoming students at the end of the first week of the semester: “Of course the most popular student in the room was James Meredith. Everybody wanted to meet him,” Falkener says with a laugh. “Here was a guy who had done something that nobody else had done.”

To Ed Weidenfeld ’68, who participated in the Selma march as an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, Meredith needed little introduction. “There was a universal respect for his commitment and his courage, his willingness to stand up to injustice,” he says.

‘He Was Doing So Much’

Meredith had served nine years in the Air Force before returning to Mississippi in 1960 and beginning his fight to integrate Ole Miss. He was 32 when he arrived at Columbia Law, with his wife, June, and 5-year-old son, John. Twins James and Joseph arrived in 1968.

“He was a fun guy,” says classmate U.W. Clemon ’68, now retired from the federal bench in Alabama. “He could be very, very serious, but around June and the kids, he was very personable.”

In their apartment on Claremont Avenue, the Merediths hosted an annual Thanksgiving party for Black law students who couldn’t travel home for the holiday. “You had a chance to really let your hair down a little bit. It was wonderful,” Falkener recalls.

But Meredith remained involved in national activism, setting him apart from his fellow students, most of whom were focused only on their studies. “He was pulled in so many directions,” Falkener says. “He was doing so much. I was just a student, had my head down trying to learn all this law.”

As a first-year student in 1966, Meredith published Three Years in Mississippi, his memoir of the integration fight. That summer, he organized a “March Against Fear” from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, to encourage Black Missisippians to register to vote. On the first day of the march, as he walked through Hernando, Mississippi with a few supporters and journalists, he was shot. The first news reports said Meredith was dead.

Almost 55 years later, Smith still remembers where he was when he heard the erroneous report: walking on West 78th Street in New York City.

“It was that kind of moment that you do remember,” he says.

Meredith had been hit with dozens of birdshot pellets in his head, back, and legs—an Associated Press photo of him lying on the road in agony won the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for photography.

Civil rights leaders, including King, took over the march while Meredith recovered. When he rejoined the group on its approach to Jackson more than two weeks later, 15,000 people marched alongside him. Historian Aram Goudsouzian, author of Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear, calls it “the last great march of the civil rights movement.”

The march put Meredith in the national spotlight again. Clemon remembers going with Meredith to meet with Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who was then working to launch the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. (Kennedy tapped Franklin A. Thomas ʼ‘63 to be the executive director.) Black political activists in Brooklyn tried to recruit Meredith to run for a congressional seat, says Clemon. Meredith had his eye on a district closer to Columbia: He launched a run as a Republican against 12-term Harlem Rep. Adam Clayton Powell in a 1967 special election but withdrew after civil rights leaders pressured him to drop his challenge.

A Lifelong Focus on Activism

Meredith’s career after Columbia Law has included teaching, business, and several brief campaigns for elected office in Mississippi. A man who describes his life’s work as a divinely inspired mission to end white supremacy, Meredith has focused much of his speaking and activism—including other, less well-known marches over the years—on improving educational opportunities for Black students and advocating for religious teaching in public schools. The Harvard Graduate School for Education awarded him the Medal for Education Impact in 2013 for integrating Ole Miss. In his acceptance speech, he criticized schools for being out of touch with the reality of Black students and said that children need to learn religious and moral values from their elders. “The problem with public school education in America today is that the Kingdom of God has been removed from the process,” he said, because teachers and adults “fear . . . what will happen to me if I help this child? The question should be, what will happen to this child if I don’t do my duty?”

In politics, he has always chosen his own path. He ran for governor and for Congress in Mississippi and then shocked many by taking a job in 1989 with conservative Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C., a civil rights opponent. (He quit two years later; Helms “was too liberal for me,” he wrote in his second memoir, A Mission From God.)

Despite his prominent place in the fight against segregation, Meredith has always chosen to remain apart from the mainstream civil rights movement. He disagreed with King’s philosophy of nonviolence, and refused to use the term “civil rights.”

“My real focus is on producing citizens without any identification. Don’t call me African American,” he said in a 2008 interview. “I am a citizen of the United States of America.”

When Ole Miss erected a statue of Meredith in 2006, in a spot near a prominent Confederate monument, he derided it as a “feel-good icon of brotherly love and racial reconciliation, frozen in gentle docility.” He called on Ole Miss to take down both his monument and the Confederate soldier. He has become reconciled to his statue at Ole Miss, which still stands despite his objections. The Confederate soldier, however, was removed in July.

This year, the demonstrations for racial justice sparked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of police give Meredith “joy and hope,” he said in a CNN op-ed in June. “White supremacy may be the most evil beast that’s ever stalked the halls of history, and today it may finally be mortally wounded.”

If it is, Meredith has done his part.

“Jim [has] had a lasting impact on the civil rights movement, because of the sheer courage and bravery that he showed in going to Ole Miss,” Clemon says. “I did admire him, and I still do.”