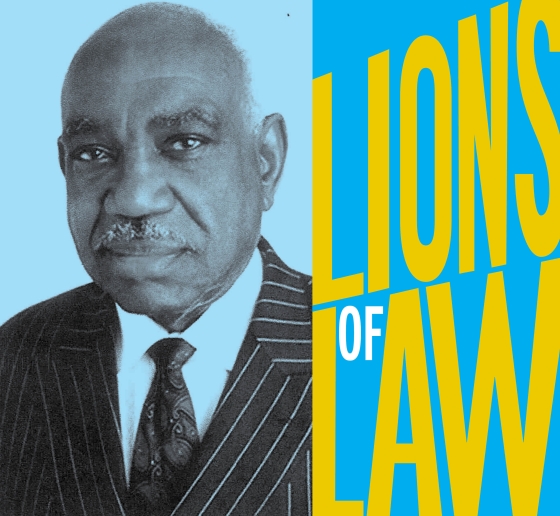

The Trials, Tribulations, and Tenacity of Judge U.W. Clemon ’68

A child of the Jim Crow South who became a civil rights activist, state senator, and the first Black federal judge in Alabama, Clemon is retired from the bench but continues to advocate tirelessly for justice and speak out fearlessly on public affairs.

When U.W. Clemon ’68 graduated in 1965 as valedictorian of Miles College, a historically Black school on the outskirts of Birmingham, Alabama, he wanted to study law. But he could not attend the University of Alabama School of Law, which did not admit Black students, despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. So he applied to Columbia Law School, secure in the knowledge his legal education would be fully funded, despite his family’s modest means.

“Yes, the state of Alabama paid for me to go to one of the nation’s best-known law schools,” Clemon says with delight, explaining it was a common practice for Southern states to pay for Black students to attend out-of-state law schools so they could keep their own graduate schools segregated.

Columbia was his first choice but not an obvious one. “Ordinarily, it would have been unthinkable for me to be admitted because I was a graduate of an unaccredited Black college,” says Clemon, noting that Miles College had lost its accreditation because its library lacked enough books. But Clemon had ambition and connections. His college’s president, Dr. Lucius H. Pitts, whom he’d gotten to know through their shared civil right activism, was a personal friend of John Davis, a founder of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) and former president of West Virginia State College. “Dr. Davis had connections with one of Columbia’s most distinguished professors, Walter Gellhorn ’31, and through the three of them, I was admitted to Columbia Law School,” he says.

Columbia was a culture shock for Clemon: He was attending a predominantly white school for the first time, and he wasn’t as prepared as his fellow students. “Roughly two-thirds of my class had graduated from Ivy League schools, so I had to work very, very hard,” says Clemon who received the Columbia Black Law Students Association’s Distinguished Alumni Award at the annual Paul Robeson Gala in 2015.

Gellhorn introduced Clemon to his former student Jack Greenberg ’48, then LDF’s director-counsel. In 1965, Greenberg put Clemon to work on an Alabama school desegregation case, Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education. “When I graduated, I handled that case myself,” says Clemon, who returned to Alabama after earning a J.D. and worked as a cooperating civil rights attorney with the LDF as he set up his private practice. “And I am still a lawyer on that case.” (Clemon resumed practicing law after retiring from the bench in 2009; he is currently of counsel to Mehri & Skalet in Washington, D.C.)

Fighting for Justice Then—and Now

Clemon has never shied away from challenges, controversies, or confrontations. As a student at Miles, he helped organize the successful boycott of stores in downtown Birmingham to protest segregation. “We called it a ‘selected buying campaign,’” he says. “The Wall Street Journal reported that in the week leading up to Easter 1962, store sales downtown were down by 40 percent.”

He also led a group that presented a petition from Birmingham residents asking the city commission to rescind its segregation ordinance, which led to Birmingham’s notoriously racist public safety commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor literally running Clemon out of town. As part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Birmingham Campaign in 1963, Clemon drank from a whites-only water fountain, and his designated group desegregated the Birmingham Public Library.

But Clemon has never been more distressed by U.S. politics than he is today.

“This country, I think, is in the worst position it has ever been in since the founding of the republic,” he says. “Oh, we had a civil war, but even then the Southern states did not try to destroy the U.S.—they simply wanted to withdraw to create their own government. [There is] a mindset that says elections don’t matter, and if a president doesn’t like how an election turns out, he can ignore it and remain in office. And Trump stacked the Supreme Court to the point that is very dangerous for the nation as a whole as evidenced by the New York State gun ruling and, of course, the abortion issue.”

Clemon is a pragmatic man of action, and he offers a way out of this dire situation. “It is my very strong feeling that for the 2022 midterms, the American people ought to elect a Senate that is composed of men and women who truly believe in justice and a majority House similarly committed,” he says. “And together they should enlarge the Supreme Court from nine positions to 13 positions.”

Although Clemon would like to see a more diverse court, he objected to the nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman justice of the Supreme Court, because of her rulings in civil rights cases. In February 2022, he sent a letter to President Joe Biden expressing his disapproval of Jackson’s conduct as a district court judge in Ross v. Lockheed, a class action on behalf of 5,500 workers at the nation’s largest federal contractor. He wrote that her rulings in Ross “gave the axe to a settlement designed to benefit numerous black workers at one of the nation’s largest employers” and denied the injunctive relief “that would have addressed a root cause of systemic racial bias that could have been a model for a nation hungry for racial equity solutions.” He also called Biden’s attention to other cases in which Jackson had ruled against Black people and women.

Still, Clemon says he applauds Biden’s appointment of a Black woman to the high court and understands why he chose Jackson. “She is extremely qualified just in terms of credentials,” he says. “She’s probably one of the most qualified persons who’s ever been appointed to the Supreme Court.”

Always a Public Figure

Clemon has made headlines throughout his career as a politician, a judge, and a lawyer in private practice specializing in employment law and discrimination. In 1969, he successfully sued legendary University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant to desegregate his team. Five years later, Clemon was one of the two Black people elected for the first time since Reconstruction to the Alabama State Senate. As a senator, he pushed segregationist Gov. George Wallace to appoint African American citizens to state boards and agencies—with mixed results.

In 1980, he became the first Black federal judge in Alabama when President Jimmy Carter appointed him to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. “I testified for six uninterrupted hours before the Senate for my confirmation,” says Clemon. He was unanimously confirmed, and he served for nearly three decades.

Although Clemon enjoyed presiding over trials and writing opinions as a judge, he says the Supreme Court’s tilt to the right after the appointment of Clarence Thomas in 1991 made his work more challenging, especially in civil rights cases. “The decisions I was bound to follow were increasingly distasteful to me, and it was difficult for me to render decisions, but I followed the law the best I could,” he says.

During his final years on the bench, he oversaw the trial in which Lilly Ledbetter successfully sued the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company for wage discrimination under Title VII. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit reversed the decision, and when the Supreme Court upheld the reversal, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 delivered one of her most famous dissents from the bench in 2007: “This is not the first time the Court has ordered a cramped interpretation of Title VII, incompatible with the statute’s broad remedial purpose. Once again, the ball is in Congress’ court. As in 1991, the Legislature may act to correct this Court’s parsimonious reading of Title VII.”

Congress heard her and passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in 2009. It was the first bill President Barack Obama signed into law.

“It was very gratifying that Justice Ginsburg took the occasion to encourage Congress to overturn what the Supreme Court had done and even more gratifying that the Congress took her advice,” says Clemon.

Celebrating Success and Overcoming Setbacks

Clemon is a towering figure in greater Birmingham, where streets and an elementary school are named for him. Despite all the progress Black people have made in the United States during his lifetime, Clemon says racism is a stubborn fact of American life. He is still working as the lead counsel in Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, the case that launched his career more than half a century ago and led to a 1971 desegregation order for Jefferson County that still governs its school district. (The case was the subject of a 2017 New York Times Magazine article by Nikole Hannah-Jones, the creator of the influential 1619 Project.)

How has Clemon stayed resilient and optimistic as incremental progress is made—and thwarted—in the fight for racial equality?

“I have a very deep and abiding faith, and if you do the things God has ordained you to do, all sorts of things will work out,” says Clemon, a longtime deacon of the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church in Birmingham. “I have always had that faith, and sometimes it’s sorely tested because battles you think you won 20 or 30 years ago resurface and have to be fought all over again. But you know God gives me strength, so I do what I think he wants me to do.”