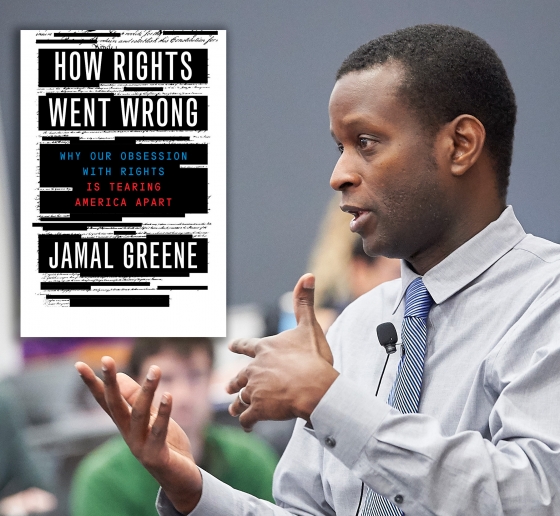

Jamal Greene Shows How Rights Go Wrong

In his new book, the constitutional law scholar argues that competing rights should be balanced through political compromise.

Guns, abortion, pandemic mask-wearing—name a hot-button issue and you’ll see the word “rights” appear not far behind. In American society, the bitterest conflicts are often framed as competing assertions of constitutional rights, allowing for no compromise.

How the focus on rights became so divisive is the subject of a new book by Jamal Greene, Dwight Professor of Law, who says courts have exacerbated ideological differences by reducing complex problems to a zero-sum assertion of one constitutional right that overrides all other interests.

In How Rights Went Wrong: Why Our Obsession With Rights Is Tearing America Apart, Greene traces the interpretation of the Bill of Rights from the framers to current legal disputes, such as the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, which pitted a baker’s claim of religious freedom against a couple’s claim of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. “The problem of the 21st century,” Greene writes, borrowing phrasing from W.E.B. DuBois, “is the problem of the rights line.”

Rights at the Expense of Justice

The book, Greene’s first, criticizes courts for narrowly framed, all-or-nothing determinations he believes award rights at the expense of justice. Too often, he says, judges decide rights cases based on textual analysis and rigid adherence to out-of-context precedent rather than by weighing the burdens imposed on both sides and considering proportional solutions that recognize that one party’s right does not have to obliterate the other’s.

“Rights disputes are about real life. They’re about people who are trying to accomplish something and other people who are on the business end of that,” Greene says. But the bias of courts for making winner-take-all decisions means “either one side is right or the other side is right, and the side that’s not right is doing something profoundly bad.” That is polarizing and essentially disrespectful, he says to the side deemed not to have rights.

A case like Brown v. Board of Education, which declared school segregation unconstitutional, is distinct, Greene says, because it seeks to end state oppression of a particular group of people. The 1954 Supreme Court correctly determined a “strong” right—to be free of racial discrimination in public education—even in an era when courts had long been deferential to states on economic matters.

But many more rights cases today involve people claiming rights against each other—the right to buy a cake from someone who does not want to make it—rather than against the state, Greene says. In these cases, “most often it’s just, we’re all trying to live our lives in a state of intense disagreement and intense pluralism.”

“Rights disputes are about real life. They’re about people who are trying to accomplish something and other people who are on the business end of that.”

Courts cannot decide rights cases without looking at facts and context, Greene says. “We think of politics as the realm where you work out something like policy, whereas rights are for courts and are supposed to be absolute and are supposed to be these august things,” he says. “And I think that that just doesn’t work for modern constitutional law.”

The Constitution is not as specific as Americans like to think. “It’s almost the shortest Constitution in the world. And its rights provisions say things like, ‘Treat people equally.’ . . . The question is, what does that mean?” The answer, Greene says, depends on contextual factors. “What are we trying to accomplish here? Are we going too far? Are people burdened more than they need to be burdened? Those kinds of questions are about facts. They’re not questions about period dictionaries or whatever James Madison might have thought. So let’s just talk about those questions rather than pretending that our Constitution lends itself to these kinds of formalisms, which it plainly doesn’t.”

Proportional Compromise

Where Rights Went Wrong grew out of Greene’s longstanding interest in “founder worship,” the propensity of Americans to lionize the Constitution’s framers, and in the “anticanon,” the term referring to decisions now viewed as wrongly decided, such as Dred Scott v. Sanford, Plessy v. Ferguson, Korematsu v. United States, and Lochner v. New York, which in 1905 allowed a business’s “right to contract” to overrule a state law setting maximum working hours for bakers.

The book also reflects Greene’s expertise in comparative constitutional law. In other countries, when judges confront questions about rights, “not only are they not focused on [their] founders, they’re not even focused on rights disputes as a matter of lawyerly interpretation of text.”

Greene is not the first legal scholar to argue that judicial interpretation of rights has become too binary; the conservative scholar Mary Ann Glendon did so in 1991. But Greene says he is more prescriptive because he urges jurists to consider proportionality analysis, an idea that is much more widespread now than it was 30 years ago.

A proportional compromise might acknowledge that both sides have some rights, Greene says, and cites as an example Germany’s approach to abortion which, while enabling women to obtain first-trimester terminations, also provides a wealth of state support for prenatal and child care that is intended to make possible continuing the pregnancy. The court, Greene writes, “forced the state to take both the rights of the fetus and the rights of women seriously.” That led to “consensus politics around maternal health and social services for women and families that Roe v. Wade helped eradicate.”

More Rights That Are Less Absolute

Greene, who joined the Columbia Law faculty in 2008, served as a clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens. Outside of the academy, he confronts free speech controversies as co-chair of the Oversight Board, an independent body set up to review content moderation decisions on Facebook and Instagram.

He blames the Supreme Court’s propensity for legalistic decision-making on the justices’ “anxiety” about their role as unelected arbitrators with life tenure. “If they have that authority, they think, ‘Well, we’d better be doing this in a way that seems lawyerly because otherwise, what are we doing here? Why isn’t this [conflict] just a question for politics?”

“We have the potential to be much better,” he says. “But we’re going down a path that is, I think, pretty destructive.”

Worse, he says, is what this type of constitutional interpretation is doing to citizens: encouraging polarization and reducing the chance of negotiation and compromise through the political process.

“If we outsource and delegate all of our rights talk to judges, and then judges treat those questions as if as if they are about commas—as opposed to being about pain and conflict—then we really lose something, which is the kind of political conversation that ordinary citizens have to have about rights questions.”

We would be better served, Greene says, by the assertion of more rights that are less absolute and by recognizing that, in conflicts, both sides have rights. That would lower the temperature of debates, he says, and force us to find solutions to the complexities of living in a pluralistic society where, for instance, the right to public health collides with the right not to get a vaccine.

Asking courts to push difficult issues back to the legislature, however, assumes the political system isn’t equally broken. And getting jurists—and litigants—to accept rulings that try to balance rights will require us to “retrain ourselves” about the dominance of one right over another, Greene says.

Balancing Rights

Despite the criticism of the way jurists are making rights decisions, “This is a pro-court book,” Greene says. “It’s not pro-court in terms of what we’ve done so far, but it is in favor of the possibility and potential of courts.”

One jurist Greene sees as sometimes attempting to balance rights is Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

“The way he tends to talk about rights in cases is not that far from how I encourage judges to talk about rights. He actually does often make a very concerted effort to try to be both respectful to and understanding of what the full stakes are. And he also is someone who believes in a certain degree of incrementalism and deference by judges,” Greene says.

For instance, in a 2019 case, in which the court ruled 7-2 that a 40-foot cross built as a World War I memorial could remain on state-owned land, Kavanaugh’s concurrence noted his “deep respect” for the argument that the cross was exclusionary and his acknowledgment that the cross is “deeply religious” and could cause “distress and alienation” to Jewish war veterans. “A case like this is difficult because it represents a clash of genuine and important interests,” he wrote. Kavanaugh also pointed out that while the court allowed the cross to stay, the state legislature could decide to move it—in other words, craft a political settlement to the issue.

Finding praiseworthy opinions from Kavanaugh could be considered a surprise since Greene served as counsel to then-Senator Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) during Kavanaugh’s contentious confirmation hearing in 2018. Harris voted against confirmation.

“He may not like me,” Greene says of the justice. “But he might like the themes of the book.”