Ezra Young ’12: A Transgender Lawyer for Our Times

The impact litigator takes on cases to ensure the civil rights of other transgender people and to advocate for systemic change and safeguards.

When Ezra Young ’12 arrived at Columbia Law School in the summer of 2009, he was determined to develop the practical tools and understand the theoretical underpinnings needed to become a civil rights attorney. “I thought I could help other transgender people vindicate their rights,” he says.

Young already had experience representing transgender people who were battling health insurance companies over coverage for conditions related to gender dysphoria. “Most public and private insurance plans have some sort of weird exclusions that create barriers to coverage, but you don’t need to be a lawyer to challenge them on behalf of other people,” says Young, who worked on the cases while an undergraduate studying philosophy at Cornell. “I was quite good at them. I did my own case first, which took a lot of studying and figuring out the issues involved. After that, I started helping others.”

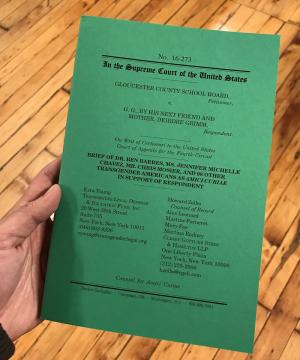

Now Young is a leading figure on the frontlines of the transgender rights movement. He has worked as director of impact litigation for the Transgender Legal Defense and Educational Fund and as a founding board member and co-chair of the National Trans Bar Association. He serves on the board of the Jim Collins Foundation, which provides financial assistance to transgender people for gender confirmation surgeries. He brought together more than 100 transgender lawyers, law students, and law professors to sign a certiorari-stage amicus brief submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court when it was considering if it would hear Gloucester County School Board v. G.G., a case about whether the Virginia school board’s bathroom policy discriminated against a transgender high school student. (The Supreme Court remanded the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, which sent it back to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, where a hearing is set for July 29.)

Health care cases continue to be one of his specialties. In 2016, Young had what he describes as a “landmark” victory when the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Medicare Appeals Council ruled that a privately run Medicare plan had to cover the vaginoplasty for his client Charlene Lauderdale “because it is reasonable and necessary,” according to the 18-page ruling.

“The decision sent a clear message: No transgender person may be denied surgical benefits simply because of outdated ideas regarding transgender health care,” Young said when the appeal was granted. “Genital reconstruction surgery is not experimental, and it is not cosmetic. It is a life-saving treatment. . . . It is our hope that many others will now be able to obtain the health care they have been so long denied.”

Ezra vs. Goliaths

One of Young’s most notable cases was the suit he filed against Amazon on behalf of a transgender woman and her husband who both worked at one of the online retailer’s warehouses in Kentucky. The couple claimed Amazon condoned its employees’ harassing and physically threatening the couple, which led them to quit their jobs. Amazon settled the case in January without admitting wrongdoing. Although Young cannot reveal the terms of the settlement, he smiles when the case comes up; clearly it is another significant victory.

For the past five years, Young has devoted much of his time to representing Rachel Tudor, who worked as a professor of English at Southeastern Oklahoma State University from 2004 to 2011. Tudor transitioned in 2007 and claimed the university subsequently discriminated and retaliated against her by subjecting her to special bathroom rules and dress codes and denying her tenure. Young sued the university and the regional university system of Oklahoma arguing their treatment of Tudor violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.

In 2017, Young brought Tudor’s case before a federal jury in Oklahoma City, which found in her favor and awarded her $1.165 million—a first-of-its-kind verdict in a sex discrimination case that went to full trial. Nevertheless, a district judge denied Tudor’s post-trial motion requesting that she be reinstated by the university or be awarded $2 million for loss of future work opportunities. Young appealed that decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, but the case is on hold since the U.S. Supreme Court announced in April that it would consider other Title VII cases, which could resolve whether the law’s prohibition of discrimination against employees “on the basis of sex” protects LGBT Americans. Young indicates that additional filings will be made on Tudor’s behalf later this summer to ensure her jury verdict is protected.

A Narrative Strategy

Young approaches litigation as a storyteller. “You can’t force people to understand humanity, but you can take them on a journey to get there,” says Young, whose solo practice is based in Brooklyn, where he is kept company by his pitbull-mix, Thurgood, whom he named after the Supreme Court justice and legendary civil rights attorney. “You have to go beyond the bare bones of proving why sex discrimination laws by definition cover transgender people. When you bring a case before a jury, you need them to care. You need them to understand what a person went through or how terrible it was and why our community values embrace this person and should protect this person.”

He believes trans bias is often based on ignorance more than enmity, and he does not want to alienate judges or jurors by shaming them and putting them on the defensive. “In most of the cases I’ve taken, the folks on the other side aren’t bad people,” he says. “They don’t even misunderstand the law. They’re just scared. They don’t see where a particular case fits in a larger historical picture. And they do, at the end of the day, want to do what’s right.”

Young prefers to take on cases in so-called red states because they generally do not have laws that expressly protect transgender people. “My idea is to use existing laws that apply to everyone—whether sex discrimination, disability, or contract laws—to guarantee that transgender people are not denied their rights,” he says. “You don't need to know someone’s sex to not discriminate against them.”

Young is concerned with creating a pipeline for transgender legal professionals. “There has been a focus on transgender people as clients but it’s also important that transgender people can actually get legal jobs,” he says. “It’s important for some clients to be represented by someone who has their shared experience. If we don’t have enough transgender lawyers in our own field that’s a problem.”

The Columbia Connection

Personally and professionally, Columbia Law School was transformative for Young. He met his wife, Justine Young ’13 (who is now a commercial litigator with Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan LLP), while working on the Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, where he was executive managing editor. He was also the online and consulting editor of the Columbia Journal of Race and Law and competed in the Harlan Fiske Stone and National Native American moot courts. After graduating, Young was a postdoctoral scholar at the Law School and focused on trans rights, critical race theory, and intersectionality under the supervision of Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw. He also served as research director for Crenshaw’s Columbia Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies and as legal director of the African American Policy Forum think tank, which Crenshaw directs.

Young maintains ties with both the center and the forum. He returns to campus several times a year to speak in Crenshaw’s classes as well as at student events, and he plans to follow in her footsteps by joining the academic teaching market once all of his major cases have been resolved.

“I don’t particularly like litigation,” he confides, “but it turned out I was pretty good at it.” Young says being a litigator was a critical opportunity to see how scholarly theories play out in the real world. “Once you have client interactions, you can tell if they are actually happy with a resolution. Even if it looks good on paper it might not actually be good for them.”

Young emphasizes that the nascent transgender rights movement faces many challenges. “Anything we do is better than nothing,” he says, “but we’re still developing a unifying strategy.”

# # #

Published June 19, 2019