Examining the Homicide Spike in Major U.S. Cities

Jeffrey Fagan and Dan Richman studied America’s homicide rates and uncovered some surprising findings.

Distrust between police and residents, a flood of illegal guns, and a high rate of unsolved murders in poor communities have fueled a rise in homicides in several major U.S. cities, an analysis by scholars at Columbia Law School shows.

The same factors that have driven the increase in homicides have also undermined the ability of police to investigate and solve murders, according to new research by Jeffrey Fagan, Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law and Professor of Epidemiology at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, and Daniel Richman, the Paul J. Kellner Professor of Law.

The study, “Understanding Recent Spikes and Longer Trends in American Murders,” appears in the latest edition of the Columbia Law Review as part of a May 2017 symposium on recent trends in crime and policing.

Police in some cities have responded to the disconnect by pulling back on investigating homicides, according to the authors, who note that the retreat contributes to a “complex and tangled ecology” of distrust and resentment that allows offenders to remain at large.

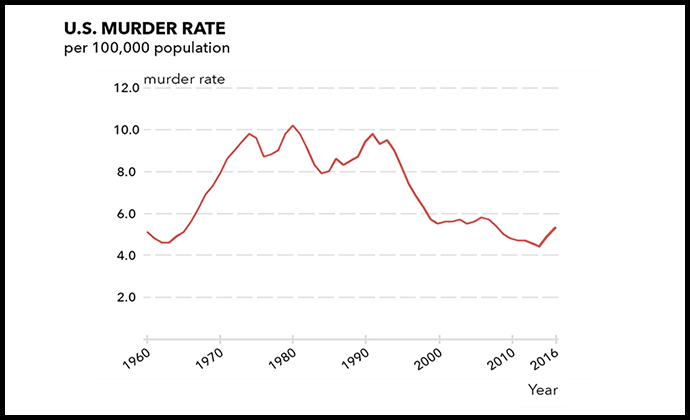

While the murder rate nationwide has trended down since 1960 and remains well below levels reached previously, Chicago has seen a spike in killings since 2015. Murder rates also have increased sharply in St. Louis, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and New Orleans over roughly the same period.

“Though killings have increased for the past two years in several cities in the U.S., we’re nowhere near approaching epidemic proportions of a homicide increase nationwide,” says Fagan. “There’s obviously something going on in Chicago that’s quite different and we believe it’s the flood of guns into the street coupled with a pullback in policing in the hardest-hit neighborhoods.”

The authors find that even this homicide spike is not the “American carnage” President Trump suggested in his inaugural address. The murders in Chicago have occurred primarily in a handful of neighborhoods on the south and west sides of the city that have seen an influx of guns and a proliferation of under-policing.

Distinguishing an epidemic

The U.S. has experienced three homicide epidemics over the past five decades, all in the 20th century, the analysis shows. Explanations for the increases and decreases vary, say the authors, who note that each epidemic tied to a proliferation of illicit drugs: heroin in the 1960s, cocaine in the late 1970s, and crack cocaine in the late 1980s.

By the end of the 1990s, rates of homicide returned roughly to the level of the 1960s before continuing to fall until through 2014. Amid the decline, the data reveal anomalies among cities that the authors note may tie to conditions in each city at any given time.

A “strikingly similar narrative”

According to Fagan and Richman, a cycle of cynicism and withdrawal has plagued law enforcement in communities of color and contributed to murders remaining unsolved. Drawing on data from a variety a series of sources in Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago, the authors observe a “strikingly similar narrative,” which they describe as follows:

“In this narrative, murders are not uncommon but remain unsolved, citizens experience policing as detached from serious crime and aimed at the wrong behaviors and the wrong people, they see police as indifferent or disrespectful if not abusive, and they are unwilling to cooperate in murder investigations by the police, whom they view as an ‘occupation force.’ These interlocking tensions reinforce the social and economic isolation of places that already have the features of a ‘poverty trap.’ Residents feel not only unsafe but unfairly treated.”

The rate at which police solve homicides and arrest perpetrators in South Los Angeles has lagged the city at large over the past two decades, according to the authors, who note that residents interpret the inability of police to “clear” killings as indifference to black homicides.

As in L.A., the neighborhood with the highest per capita murder rate in New York City, the South Bronx, had (until a series of articles in The New York Times shed light on crime there) the fewest detectives assigned per violent crime in the city.

A gun “epidemic” in Chicago

In addition to a worsening of relations between residents and police, Chicago has endured a flood of illegal guns that has intensified violence there. Fagan and Richman map dozens of firearms dealers around the city’s south and west sides and along the state’s border with Indiana.

Data suggest that guns used in killings come from these dealers, according to the authors, who note that police in Chicago seized about 8,300 illegal guns last year, a jump of nearly 30 percent from the number seized in each of the three years that preceded it. The rate of gun homicides in Chicago in 2016 was nearly twice the rate of that in Philadelphia, the next-highest big city, the analysis shows.

The proliferation of guns in Chicago coincided with a spike in homicides, which jumped 762 in 2016, an increase of 80 percent from two years earlier.

The surge in violence in Chicago also was preceded by a pullback in policing, particularly following the release of a video that showed the shooting of Laquan McDonald, an unarmed teenager killed by police in 2014. That differs from New York, where homicides continued to fall after police ratcheted down the number of stops.

Fatal encounters with police

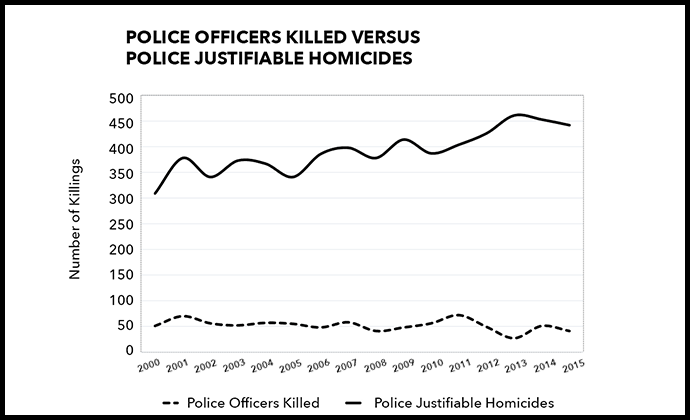

An increase in killings of civilians by police also contributes to conflict. As the chart highlights, the number of police killed in the line of duty has trended down since 2000, while killings of civilians by police have increased.

Fagan and Richman also cite data chronicling the increase in detail. The counts converge on an uptick in police killings of citizens during the three years that ended in 2015.

Video of the shootings fuels anger and resentment. “It’s not lost on citizens of other cities what happened to Philando Castile,” says Fagan, referring to the Minnesota man fatally shot last summer by a police officer during a routine traffic stop.

A shift to investigating homicides with the promise of bringing offenders to justice and away from stopping people proactively with its potential to produce injustices and indignities may help police to rebuild trust in vulnerable communities, the authors suggest.

Watch Fagan explain the roots of Chicago's homicide spike:

Related:

Understanding Recent Spikes and Longer Trends in American Murders

###

Posted on July 19, 2017