Eric H. Holder Jr. ’76: Advocating for Fair Elections

A longtime champion of voting rights, the 82nd Attorney General of the United States is working to end partisan gerrymandering across the U.S.

When Eric H. Holder, Jr. CC ’73 LAW ’76 was stepping down after more than six years as the nation’s first Black Attorney General, he and then-President Barack Obama had a conversation about the obstacles that had bedeviled the administration. “More than a few of the things that we wanted to get done were stopped by a gerrymandered House of Representatives,” says Holder, senior counsel at Covington & Burling, where he has worked since leaving the U.S. Department of Justice in 2015. “I decided I wanted to figure out how we ended up in this situation.”

Looking back to the 2010 midterm elections, Holder recognized that they were a turning point. “You ended up with a House of Representatives where Republicans had a 49-seat majority, and that was just a total function of gerrymandering,” he says. “That may sound cynical, but that was the deal.”

Holder was determined to right what he considered a pernicious wrong. In 2017, he founded the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), a nonprofit that works to raise awareness about redistricting, encourages public involvement in the quest for fair maps, and files lawsuits against gerrymandered maps. “Gerrymandering is something that has a negative impact on our democracy, and it puts in place governments that don’t reflect the policy desires of the American people,” he says.

Although it endorses candidates in specific elections, the NDRC has a nonpartisan goal: “Our aim is to make the system more fair,” Holder says. “Our theory is that if the system is fair, … our democracy will be better. I don’t stand for gerrymandering for Democrats, and I stood against Democrats in Maryland who were trying to gerrymander in that state. The NDRC looks for ways in which we can enhance our democracy and come up with governments that are responsive to the needs and desires of the American people.”

Holder tracks what he calls the decline of faith in U.S. democracy in a few moves: In gerrymandered districts, both Republican and Democratic officeholders don’t care about running against opponents in a general election because they know they’re going to win, he explains. But they do care about avoiding primary challenges. “They don’t want to be seen as reaching across the aisle because that’s a sign of weakness that invites a primary challenge,” he says. “Which means there are no compromises, and little or nothing gets done in the legislature. And that breeds cynicism in the American people about the effectiveness of government.”

He continues: “It also means that we think we’re a divided nation, and we’re not as divided as people think. Our political class is very divided! [But] on the big issues, the American people are basically in agreement when it comes to sane gun laws, climate protection, reproductive rights, and voter rights. But you couldn’t get policy determinations that reflect this level of agreement from gerrymandered state legislatures and the House of Representatives until recently, when we were able to erase a lot of the gerrymandering on the federal side.”

Holder also points to big Supreme Court wins the NDRC had in 2023. Its affiliate, the National Redistricting Foundation (NRF), initiated and directed the legal strategy of the case that was consolidated as Allen v. Milligan, in which a 5–4 majority ruled that Alabama’s 2021 congressional map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and illegally diluted the voting power of Black Alabamians. The NRF also directed the legal strategy in Moore v. Harper, which challenged voting maps in North Carolina; the justices ruled 6–3 that the Constitution’s Elections Clause does not vest exclusive, independent authority in state legislatures to set rules regarding federal elections.

Holder says the NDRC has also made strides by facilitating ballot initiatives in both red and blue states—Michigan, Colorado, Virginia, Utah, Missouri—that created independent redistricting commissions.

The Path to Public Service

Holder has been interested in voting rights since his childhood in Queens, New York. He remembers being 12 and watching television reports of primarily Black marchers for voting rights crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, and being brutally attacked by state troopers. “It left a big impression on me,” he has said.

As a student at Columbia College from 1969 to 1973, Holder was politically active during a tumultuous era. He participated in student strikes and a peaceful sit-in on campus that ultimately led to the creation of a Black students’ lounge. After graduating with a degree in American history, he wasn’t sure what to do next. “I saw law school as a kind of haven for the undecided,” he says. “I had such a positive experience at the college that I decided to go to Columbia Law School. I had gotten into Harvard Law School and said, ‘No, I’d rather go to Columbia.’”

During his 1L year, he took criminal law with Professor Telford Taylor, who was a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials. “He was such a great example of what the law can do,” says Holder. “I didn’t really decide I wanted to be a lawyer until my class with Telford Taylor; that really influenced the arc of my career.”

When he graduated from the Law School, Holder joined the Department of Justice, where he was a litigator in the Public Integrity Section. After 12 years at the DOJ, he continued his public service career as an associate judge on the Superior Court of the District of Columbia (1988–1993), the first Black United States Attorney for the District of Columbia (1993–1997), and the first Black Deputy Attorney General of the United States (1997–2001) before going into private practice at Covington & Burling. He returned to government service in 2009 when then-President Obama nominated him to be the 82nd Attorney General of the United States, and he became the first Black person to serve in the position.

By then, Holder was used to the responsibilities that come with being a trailblazer and role model. “As a ‘first,’ you feel an obligation to the people who made the opportunity for you possible, the people who sacrificed, protested—a whole range of things to give you the chances that they didn’t have,” he says. “And there’s a pressure that people will say, ‘He was chosen just because of his race,’ that ‘he’s not there because he’s qualified but because somebody is trying to make a political statement, a cultural statement.’ So there’s a dual pressure you feel not to disappoint and then to prove your worth.”

Holder says the burdens he shoulders are nothing compared to that of pathbreakers like his late sister-in-law, Vivian Malone, and baseball legend Jackie Robinson. Malone was one of two Black students who integrated the University of Alabama in 1963, defying Gov. George Wallace, who stood at the door to block her entry before she was escorted inside by the National Guard; two years later, she became the university’s first Black graduate. Robinson, who integrated Major League Baseball, was mercilessly derided and harassed by players and fans. “I’ve gotten to know his widow, Rachel Robinson, and learned about the threats their family faced,” says Holder. “I had a picture of Jackie Robinson in my office when I was Attorney General, and I have one in my office now to remind me that whatever pressures I feel pale in comparison to what he and my sister-in-law had to go through.”

Columbia Connections

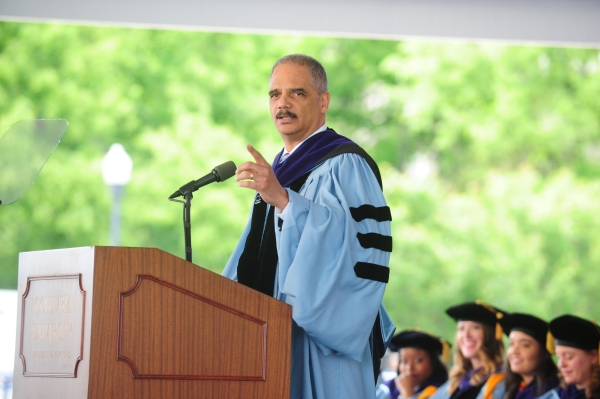

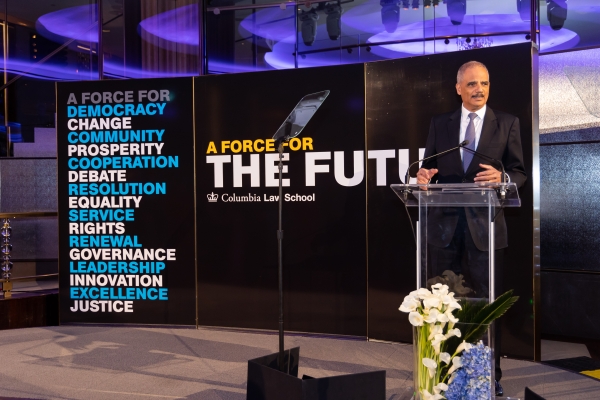

Holder maintains deep ties to the Law School. He received the Medal for Excellence in 2010 and was the keynote speaker at the 2016 graduation ceremony. That same year, alumni and friends established the Eric H. Holder Jr. Scholarship Fund, and the Black Law Students Association (BLSA) created an Eric H. Holder, Jr. scholarship. BLSA also honored him at its 25th anniversary gala, and in 2023, Holder delivered the keynote address at the celebration of the conclusion of the five-year Campaign for Columbia Law.

He is also a committed supporter of Columbia College and, in 2017, founded the Eric H. Holder, Jr. Initiative for Civil and Political Rights, which engages students in election issues through its American Voter Project (AVP). He recently participated in an on-campus conversation, “Looking Ahead to the 2024 Elections,” sponsored by AVP.

Beyond the upcoming election, Holder and the NDRC are already planning for the redistricting that will occur in 2031 based on the 2030 census. “I think that, too often, we as Americans think about civic engagement episodically, only during presidential election years,” he says. “There’s a high level of interest right now, but come December, people will go back to their lives. From my perspective, if we are going to bring about the changes I think we need, we have to play the long game.”

Holder says Columbia students have “an obligation” to be changemakers and involved in civic life. “My hope is that Columbia students feel that sense of responsibility, use the awesome talents they have, the influence they will undoubtedly obtain, to make our democracy better, to live up to its founding ideals,” he says.

Although he’s now in private practice, Holder considers himself a public service lawyer first. And for all his successes, he remains humble. “I’ve held a number of important titles in my life, but the most important title I’ll ever hold is that of ‘American citizen,’” he says.