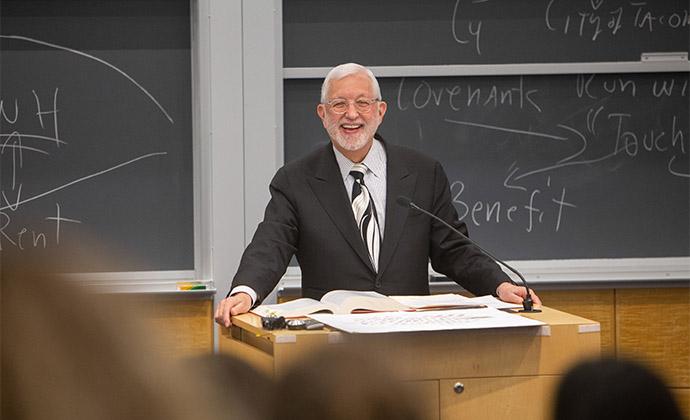

Columbia Law Students Get Real-World Lessons From Federal Judge Jed Rakoff

As a judge on New York’s Southern District bench, Rakoff brings a fresh, hands-on perspective to the first-years in his Criminal Law class.

The defendant was a mid-level enforcer for the Genovese crime family who was pleading guilty to attempted murder after cooperating with prosecutors to put away 19 senior mobsters. In the course of his cooperation, the perp had admitted to a separate murder committed many years earlier.

“What sentence should he get?” the adjunct professor asked the first-year Criminal Law class.

By a show of hands: 10 years in prison, at least.

He got four years—handed down by the professor himself. Judge Jed Rakoff had imposed the sentence in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York that very day before heading uptown to teach a section of Columbia Law’s introductory Criminal Law course.

Hot Takes on Criminal Justice

The opportunity to discuss a case fresh off the bench is a unique benefit of taking Rakoff’s class. More than 100 students get on-the-spot perspective and insights into judicial analysis and decision-making.

“It is impossible to make a case against higher-level mobsters without a cooperator,” Rakoff told his class. Obtaining cooperation requires offering a reduction in sentence. Not only would word of the lighter sentence spread among the “criminal community,” Rakoff said, but the enforcer had also provided “substantial” help in convicting his mob bosses. “In my book, they’re a lot worse than this guy, bad as he was.”

Rakoff has long taught third-year seminars on subjects including white-collar crime and science and the courts, but this year Dean Gillian Lester, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, persuaded him to take on Criminal Law, a required course. Rakoff now gets to teach a 1L course the way he has always believed it should be taught: with real-world examples. He even took his class on a field trip to his courtroom during a felony murder trial.

Thanks to his 23 years on the bench and 50 years in law, Rakoff has likely experienced a case to illustrate everything on the syllabus. As a judge, he has become known for his decisions in complex white collar crime cases, including rejecting settlements negotiated by the Securities and Exchange Commission that he ruled were inadequate in amount and gravity. He also has been a strong advocate for criminal justice reform, arguing that the large number of cases decided by plea bargain put too much sentencing power in the hands of prosecutors instead of judges.

In 2002, Rakoff ruled that the death penalty violates the constitutional right to due process because execution deprives the convicted of the ability to prove their innocence when new evidence emerges after their conviction. But in discussing the death penalty with his 1L students, he also shared his personal experience of loss: His older brother Jan was murdered in the Philippines in 1985, and the assailant received only three years in prison.

It was “a particularly poignant moment,” says his teaching assistant, Andrew Kuntz ’19. “I think [it] helped convey to the students that, though he may disagree with the death penalty, he also understands that the sense of justice it can bring for the family members of the victim is something that’s hard to calculate.”

A Different Kind of Class

Rakoff often asks for comment from the class about questions that aren’t easily answered, such as how to define a standard for civil commitment or why an insanity defense is seldom successful. “Most jurors think it’s a big fake,” he told the class.

“Criminal Law feels like a different class than a lot of the black-letter classes because it has got such open-ended and moral topics in it,’’ says Hanna Yindra ’21. “I do like that he pulls us and pushes us to consider our own moral biases and standpoints.”

Rakoff polls his students regularly, such as with the sentencing question. As a result, the class can feel like “a rather large seminar,” Kuntz says, where doctrine and cases matter but there is emphasis on discussion and participation.

Before agreeing to teach the class, Rakoff consulted Gerard Lynch ’75 and Debra Livingston, both judges on the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals and tenured professors at Columbia Law, and his brother Todd Rakoff, who teaches at Harvard Law School.

“They all said the same thing, which is, it’s exciting to teach first-year students,” Rakoff says. “I’m constantly interested to see how [students’] minds are developing."

Rakoff went into the semester determined to make the class he teaches different from one he took as a student at Harvard Law in the 1960s. “That was the Paper Chase era,” he says, referencing the 1973 film about a struggling Harvard Law 1L. “There was a good reason not to raise your hand, because you were going to be humiliated by the professor. I hope I never have done that.” Instead, each week he puts 10 students on notice that he may call on them if no one volunteers to answer a question.

In addition, he says, the criminal law class he took was a “huge disappointment” because it was entirely focused on policy and had “very little practical sense.”

“I’m trying to give them a feel for how things work in practice,” he says. “I think the main thing I bring to the table is the reality check.”

Rakoff wants his students to learn two things. First, they must distinguish legal issues from the facts at hand. Second, he says, “Don’t assume that the doctrines of the law are what really drive the outcomes.” When a criminal defense lawyer makes his unsavory client look sympathetic or the victim appear unsympathetic, “In theory, neither of those things has anything to do with what the jury’s job is. . . . There’s a lot going on in these cases that is not a question of just applying the instructions of the law.”

He has a significant caution for students who go into criminal law—and for anyone working in the criminal justice system.

“We think we give greater protection to the innocent than we do,” Rakoff says. “We have the presumption of innocence, we have the requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, we have the Fifth Amendment right to silence.” But the increasing number of exonerations of convicted prisoners, even from death row, say otherwise, he notes. For years, lawyers and judges believed that while guilty people may occasionally get off, an innocent person would never be convicted. “It’s important for my class to know that’s not true.”

# # #

Published on May 2, 2019