What "Ferguson Effect"? Understanding Recent Ups and Downs of Crime

Tracey L. Meares

Walton Hale Hamilton Professor of Law

Yale Law School

Jeffrey Fagan

Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law

Columbia Law School

June 3, 2015

Every loss of life is regrettable, and every loss should be mourned. We begin with that lest someone attempt to take what we say next out of context: this-time-last-year crime comparisons are (almost) meaningless.

Using this method some have argued that the decades long crime decline may be ending. The evidence? A recent “spike” in shootings and violence based on percent increases “over the same period the previous year” in an odd, small and curated collection of cities. This “sky is falling” prediction is more sophistry than science. For one thing, “percents” tend to inflate small differences into large ones. They grab attention, but they don’t mean much, especially when those numbers are small. Asking whether the rate has gone up puts these numbers in a richer perspective and gives them greater meaning and comparability from place to place. Comparing one time period with another also runs the risk of dramatizing temporary but practically small changes. Extending the comparisons over time is a better approach and can yield some interesting results.

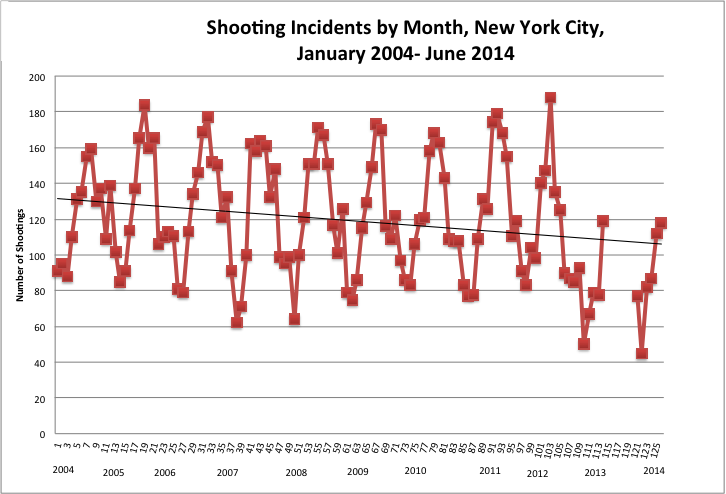

For example, in New York City, we know that shootings have "spiked" in May nearly every year since at least 2004. Crime goes up as the weather gets warmer, but within a few months, the rates settled back into the longer decline. We’ve seen this dynamic before. Back in 2006 there was an increase in the murder rate, but the long-term decline resumed the next year and continued through 2014. In 2012, there was a May spike in shootings, but again, shootings receded by the end of the year.

Source: NYPD, OMAP, various years

There was even a similar panic in May of last year, but 2014 ended with a low murder rate not seen since 1963. Figuring out whether crime is going up, down or remaining the same requires a longer time series with numbers that make sense.

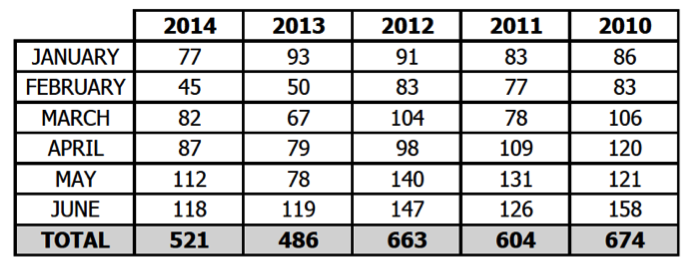

Shooting Incidents by Month, New York City,

Jan 1 – June 30, 2010-2014

Source: NYPD, OMAP, various years

A second recent claim is that a “Ferguson effect” is driving the crime increase. The argument is that cops are backing off from their jobs for fear of criticism or even losing their jobs. The evidence for this claim is a couple of anecdotes, but anecdotes here simply won’t do. We need real evidence that policing has changed for the worse, and that those changes are tied to crime changes that are also real (Consider the previous argument.) Where we’ve seen evidence of real changes in policing, it has not been associated with a change in crime. Last winter, when a dramatic shift in pace of police work in New York City resulted in a sharp drop in arrests and summonses, there was no spike in crime. And in 1997, when the police stopped writing traffic tickets for several months in a contract showdown with Mayor Giuliani, there was no spike in crime.

We need better evidence than a few anecdotes to sound the alarms of Armageddon. Instead, we have yet another dog who doesn’t bite.

TLM and JF

New York, NY

June 3, 2015

*A version of this essay appeared in The New York Times on June 5, 2015