Study Questions Constitutionality of NYPD Use of Marijuana Arrests to Fight More Serious Crime

Study Questions Constitutionality of NYPD Use of Marijuana Arrests to Fight More Serious Crime

Media Contact:

Public Affairs Office, 212-854-2650 [email protected]

March 30, 2011—New York Police Department (NYPD) efforts to use arrests for marijuana possession as a way to crack down on more serious crime often fall short of their goals, may be unconstitutional, and mostly target minorities, research by Professor Jeffrey Fagan contends.

The study, conducted by Fagan, a nationally recognized expert on policing and criminal law, and Amanda Geller, an associate research scientist at the Columbia University School of Social Work, analyzed 2.2 million police stops and marijuana arrests from 2004 to 2008.

“Police like to use marijuana as a pretext to crack down on more serious crime, but there’s little evidence to suggest this is an effective strategy,” Fagan said.

At issue is the city’s “Order Maintenance Police” (OMP) program, which the NYPD has designed to target low-level offenses, such as possession of small amounts of marijuana, through the aggressive use of “stop, question, and frisk” tactics in high-crime areas. The police department has defended the strategy as an effective way to reduce crime and get guns off the street.

The thinking behind OMP is that individuals detained for such offenses “were likely to be carrying weapons … or be on their way to or from robberies or other violent crimes,” according to Geller and Fagan.

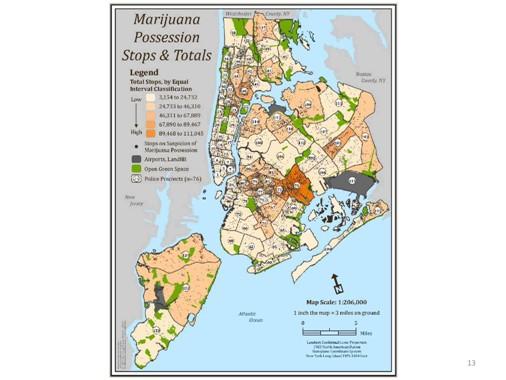

Their article, Pot as Pretext: Marijuana, Race, and the New Disorder in New York City Street Policing, published in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, shows the degree to which police have focused on marijuana enforcement, noting that by 2000, marijuana possession accounted for 15 percent of all adult arrests in the city. By 2006, marijuana arrest rates had increased fivefold from just a decade earlier. In all, there were about 52,000 marijuana stops from 2004 to 2008 that did not result in arrests.

The problem: there’s little indication the strategy works, Fagan said. The authors found less than 4 percent of marijuana stops led to an arrest and less than one half of 1 percent led to the seizure of a weapon. And since marijuana arrests rise each year, there are no signs that arrests are an effective deterrent, he added.

Geller and Fagan also found the street stops for marijuana, like street stops generally, take place “disproportionately” in predominantly black neighborhoods. For example, blacks were 7.5 times more likely than whites to be stopped for suspicion of marijuana possession. Hispanics were 2.75 times more likely to be stopped than whites.

As Fagan has found in other studies, “marijuana enforcement seems to be focused not on violent crime, but on predominantly minority neighborhoods.”

Such targeting is “dramatically out of proportion to national statistics that suggest comparable usage rates across racial groups or higher rates of marijuana use among whites,” Geller and Fagan write.

The police department has rejected accusations of racial profiling in stop-and-frisk operations.

An analysis Fagan co-authored in the Journal of the American Statistical Association found that, in a 14-month period ending in March 1999, blacks and Hispanics represented 84 percent of all stops, even though they represented half of the city’s population.

“This is not to say the NYPD is racist,” Fagan said. “However, some police tactics appear to be based on perceptions that have no basis in reality.”

Under key U.S. Supreme Court decisions governing stops, police are required to have a “reasonable and articulable” suspicion before making a stop. However, Geller and Fagan found many instances where stops were “constitutionally insufficient,” such as merely being present in a high-crime area when police are looking for criminal activity.

“The legal rationales for marijuana enforcement also suggest both a racial skew and a pretextual nature of citizen stops and marijuana arrests,” Geller and Fagan write. “Despite recent litigation requiring police officers to specify the reasons for each stop, we find recurring patterns of stops that lack legal justification under both federal and New York law.”

# # #

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, stands at the forefront of legal education and of the law in a global society. Columbia Law School joins its traditional strengths in international and comparative law, constitutional law, administrative law, business law and human rights law with pioneering work in the areas of intellectual property, digital technology, sexuality and gender, criminal, national security, and environmental law.

Visit us at www.law.columbia.edu

Follow us on Twitter http://www.twitter.com/columbialaw