Students Monitor Voting on South Dakota Sioux Reservations

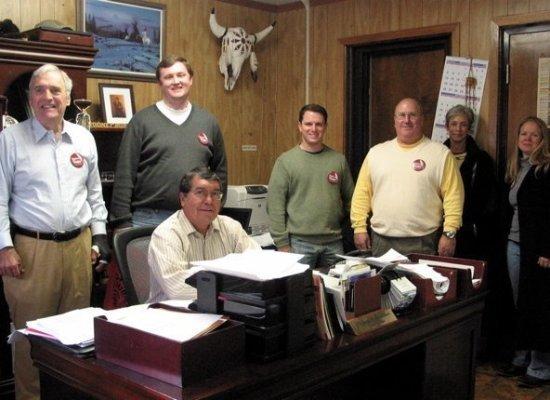

Greg Lembrich '03 (second from left) with Rosebud Sioux Tribe Chairman Rodney Bordeaux

(seated) and other members of the voting-rights group Four Directions (photo courtesy of Stephanie

More recently, Four Directions beat back efforts to limit polls to white-dominated parts of counties where Native Americans are the majority, and this year fought to ensure access in those counties to early voting, which was freely available in the rest of South Dakota. But this past Election Day, any major problems seemed to have dissipated, Watts said.

Peter Sheppard Tim Edmonds Shawn Watts

The only real issue the students encountered was potential voters who did not know they had to register. Instead, the students helped with registration forms so those residents would be ready for the 2012 election.

The students, who paid their own expenses, said even if they did not uncover any wrongdoing, the trip was rewarding and plan to return.