State Departments Top Economic Adviser Says U.S. Cannot Retreat from Global Economy

Media Contact:

Public Affairs Office 212-854-2650 [email protected]

New York, March 9, 2010—Robert Hormats may have a high-ranking position in the State Department, but what he really spends much of his day on is trying to solve puzzles.

In this case, the puzzles – for which there are never easy answers – involve how to shape President Obama’s international economic policy. As Under Secretary of State for Economic, Energy and Agricultural Affairs, Hormats, who recently visited Columbia Law School, has a job that inevitably places as much weight on sales as it does diplomacy.

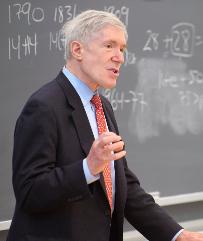

“We must connect with Main Street. You can’t be in the ethereal level of economic principles. It has to relate to the concerns that average Americans have about their jobs, their communities, their economic security,” said Hormats, in an event sponsored by the Law School’s Center on Global Governance as part of its spring semester speaker series run by professors Richard Gardner and Michael Doyle (left and right).

At the same time, Hormats said it is imperative to explain that the success of the domestic economy hinges on the “overall functioning of the global economic system.”

One of the front-burner issues for Hormats, who serves as the top economic adviser to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is globalization. Hormats must help combat the perception that globalization has “worked to the disadvantage” of Americans. He insists the U.S. has little choice but to embrace vigorous international trade.

“The more free-trade agreements that are reached the U.S. are not a part of, the more market share we will lose,” Hormats said. “We’re trying to figure out a way of dealing with this reality and working with it in a more comprehensive way.”

A linchpin of that strategy is working with emerging economies and showing how U.S. policies are responsive to their needs, including access to basic health care, food security, and the ability to rise out of poverty.

Hormats, who previously was vice chairman of Goldman Sachs, knows that can be a lot easier said than done.

“You can’t just say, here’s our agenda, take it or leave it,” Hormats said. “Our agenda has to shift, our priorities have to bend somewhat to accommodate the needs of these countries as well. That, for a country used to calling the shots for a very long time is an adjustment in itself.”

That is especially true, he said, when dealing with the so-called BRIC nations–Brazil, Russia, India, and China--that are among the world’s biggest economies even if they are not among the richest countries. That dichotomy can make negotiating effective trade agreements tricky.

“We have to understand that as they look at the global system they’re looking at it from the point of view not as countries that are rich and industrialized, but as countries that have a lot of very poor people,” Hormats said.

Still, they are countries with more than 2.7 billion people, an increasingly potent middle class and significant upsides to their economic prospects long-term. In turn, Hormats said any global economic issues need to be resolved with their concerns in mind.

“The goal is to bring them into the system but also take responsibility for the system,” Hormats said. “They can’t only be our rules. They have to be rules that are worked out collectively.”

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, stands at the forefront of legal education and of the law in a global society. Columbia Law School joins its traditional strengths in international and comparative law, constitutional law, administrative law, business law and human rights law with pioneering work in the areas of intellectual property, digital technology, sexuality and gender, criminal, national security, and environmental law.

Visit us at http://law.columbia.edu

Follow us on Twitter http://www.twitter.com/columbialaw