Spring IP Speaker Series at CLS: Museum Deaccessioning Issues

Some of the priciest art works on today’s auction block come not from private collectors but museums and educational institutions. Selling off works from a collection, known as deaccessioning, has sparked questions among art experts, lawyers, the courts and the public about the cultural value of possessing an object versus the commercial value of selling it.

These complicated issues were debated at “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do: Issues of Museum Deaccessioning,” hosted by the Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts at Columbia Law School. The panel, held March 11, was part of the Kernochan Center’s Spring IP Speaker Series.

| Jane A. Levine (left) moderated the discussion, while panelists C. Michael Norton (center) and Lee Rosenbaum (right) offered diverging views on Fisk University's fight to deaccession two objects from its Stieglitz Collection. |

||

“There’s a balance between safeguarding public trust and fulfilling the mission of the institution,” said moderator Jane Levine, who is Senior Vice President, Worldwide Director of Compliance for Sotheby’s. Striking that balance can sometimes turn into a battle among the museum, courts and intervening parties.

Among the many questions at play when museums consider whether to deaccession an object are: What is the institution’s mission and how does the object fulfill it? Is the museum part of a larger institution with a broader mission? What is the object’s cultural value to the community? Did the object’s donor place restrictions on the gift or express a specific intent for it? The American Association of Museums (AAM) and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) also stipulate ethical guidelines for deaccessioning that member institutions must follow.

Opponents to deaccessioning often criticize the rationale that purchasing new objects merits shedding the old.

“Mission creep” is how panelist Lee Rosenbaum, an arts journalist, critic and blogger, views a museum’s justification to sell off older objects in order to buy works by today’s favored artists. She pointed to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y., as a representative example.

Albright-Knox cited its focus on modern and contemporary art when it decided to sell 207 antiquities, Medieval and Renaissance art objects to raise funds to compete in the tough buyer’s market for contemporary works. Community members filed suit in 2007 to stop the sale, charging that the museum misrepresented its mission. The lawsuit was dismissed, and the auction brought more than $67 million to the Albright’s coffers.

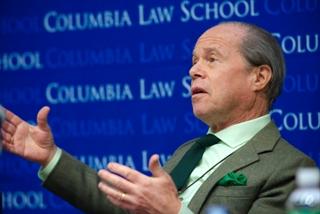

Ronald D. Spencer described controversies surrounding the Barnes Foundation Collection in Merion, Penn.

A museum’s mission also comes under scrutiny when it seeks to alter its practices, even while keeping a collection intact. The Barnes Foundation in Merion, Penn., for example, has applied to the court numerous times to make changes – other than deaccessioning – it deems necessary to stay financially afloat.

The process has been especially arduous as the courts pick through numerous – and sometimes contradictory – specifications of deceased founder Albert C. Barnes to determine his original intent for the collection, said panelist Ronald D. Spencer, head of the art law practice group at Carter Ledyard & Milburn.

In 2004, the Barnes Foundation won a two-year effort to change its charter and relocate from Merion to Philadelphia, to increase visitor traffic and revenue. Directors believed the move would help realize Barnes’ goal of making art accessible to the greater public. Those opposed argued that moving the collection violated Barnes’ wishes. The move has yet to take place.

Nonprofit institutions that hold art, like libraries and universities, also face strong resistance to deaccessioning. Controversy erupted when Thomas Jefferson University, a medical school in Philadelphia, voted in 2006 to sell “The Gross Clinic,” a treasured oil painting by American realist Thomas Eakins (1875). The painting was to go to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, founded by Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton and under construction in Bentonville, Ark.

Ultimately, “The Gross Clinic” did not end up there but instead went to the Philadelphia Art Museum and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, which raised $68 million to keep the painting in Philadelphia. A copy now hangs where the original once did at the school.

Patty Gerstenblith discussed the legal principles guiding decisions about museum deaccessioning.

Some of the most bitter controversies occur at universities with embedded museums, said panelist Patty Gerstenblith, director of the DePaul College of Law’s Center for Art, Museum and Cultural Heritage Law. Unlike many large museums, most embedded museums – those museums which are part of a larger nonprofit organization such as a university – are not members of the AAM or the AAMD, but they still answer to their donors and the community.

A high-profile fight has been underway for years at Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tenn., and the home of the Carl Van Vechten Gallery. The embedded gallery does not have its own board of trustees; decisions are left to the university trustees.

Fearing having to close and looking to replenish an endowment that had dwindled significantly, Fisk has sought court approval to sell an interest in two specific works from the Alfred Stieglitz Collection, a set of 101 pieces of American art housed at Van Vechten with an estimated total worth of more than $100 million. Stieglitz’ wife Georgia O’Keeffe gave the works to Fisk University in 1949.

So far, the university has failed to gain approval to sell off the 1927 Georgia O’Keeffe painting “Radiator Building – Night, New York” and to sell a half-interest in the painting to Crystal Bridges Museum for $30 million, which would split its display time between Nashville and Bentonville, Ark.

In February 2008, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M. which represents O’Keeffe’s estate, sought to take the entire collection from Fisk for violating the terms of her donation when it attempted to sell these works. In March, a Nashville judge ruled that Fisk, although it broke the terms of O’Keeffe’s gift conditions, should not lose the collection to the O’Keeffe Museum.

Some believe that regardless of the donor’s intention, it is never appropriate for boards of colleges to sell off pieces of an embedded museum in order for the larger institution to stay fiscally solvent.

Rosenbaum argued that Fisk and other institutions are ignoring the value of art – both to the embedded museum and to the educational mission of the larger institution – and treating collections as sources of ready cash when the financial going gets tough.

Rosenbaum emphasized the duty such nonprofits as educational institutions and museums have to the public, who help subsidize them by paying for their tax-exempt status.

“Selling art is a very easy way to compensate for the failure of management to get support,” Rosenbaum said. “Institutions are trying to raise quick cash through selling art, rather than doing fundraising the old-fashioned way.”

Panelist C. Michael Norton, whose law firm Bone McAllester Norton represents Fisk in litigation over the Stieglitz Collection, gave a different perspective.

“When you’re a trustee of a university, do you see a painting or do you see a new science building?” he asked. “It’s where reality meets ethics, and reality needs to win.”