The Roles of Congress and the President in U.S. Foreign Policy

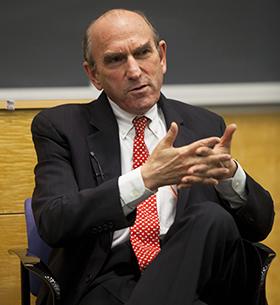

Elliott Abrams, Former Special Assistant to the President and Deputy National Security Adviser in the George W. Bush Administration, Critiques America's Global Strategy

New York, October 22, 2014—The U.S. Congress mostly plays a reactive role in contemporary American foreign policy, argued Elliott Abrams, a former senior national security official in the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations, in an Oct. 9 talk at Columbia Law School.

| Elliott Abrams, a former senior national security official, speaks at Columbia Law School on Oct. 9. |

“Congress does not have the ability to make foreign policy out of whole cloth,” said Abrams, in a wide-ranging conversation with former colleague Matthew C. Waxman, the Liviu Librescu Professor of Law and faculty chair of the Roger Hertog Program on Law and National Security. “The role of Congress now is essentially supporting or opposing the president.”

The session was part of a seminar titled “Congress in American Foreign and Defense Policy” that Waxman co-teaches with former Senator Joseph I. Lieberman and Vance Serchuk.

The session was part of a seminar titled “Congress in American Foreign and Defense Policy” that Waxman co-teaches with former Senator Joseph I. Lieberman and Vance Serchuk.

Abrams, now a senior fellow for Middle Eastern studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, said that Congress’ foreign policy influence has dwindled as ubiquitous media exposure has eroded opportunities for lawmakers to negotiate candidly in private.

“Television ruined the legislative mark-up process,” said Abrams. “There’s no open or honest debate, just a lot of public grandstanding.”

When Waxman, formerly principal deputy director of policy planning at the U.S. Department of State and special assistant to the national security adviser at the White House, asked Abrams what he thought of the criticism that George W. Bush oversaw a unilateralist imperial presidency, Abrams said the charge is more applicable to the Obama administration.

“Obama did not get authorization for action in Iraq and Syria like Bush did,” Abrams said. “And [Obama] has taken unilateralism on domestic issues much further.”

Abrams said the Bush administration was right to remove Saddam Hussein from power, but it went in with inadequate planning for the post-war period and subsequently misjudged Iraq’s domestic situation. He also criticized the Obama administration for putting insufficient pressure on Iran in ongoing nuclear negotiations, and for backing off rhetoric that Syria’s Assad regime had crossed a “red line” in using chemical weapons on the Syrian people. In the long run, Abrams argued, it is in the U.S. national interest to align with democratic reform movements against dictators and strongmen.

Despite continuing unrest in the Middle East, Abrams said he was hopeful that the region will eventually embrace liberal democracy.

“It’s going to be a long time before there are legitimate, decent governments ruling all of Iraq and Syria,” Abrams said. “But I do not accept the notion of Arab exceptionalism, that all peoples desire freedom except Arabs.”

| Professor Matthew C. Waxman and Abrams share a wide-ranging conversation on U.S. foreign policy. |