For Real? Legal and Economic Perils of Art Authentication

Media Contact: Public Affairs, 212-854-2650 or [email protected]

New York, Nov. 29, 2011—Today’s vibrant global art market is frequently overshadowed by a thriving business in art forgery. With worldwide art sales said to exceed $50 billion—and estimates of forgeries as high as 40 percent—how do experts determine if a work of art is authentic?

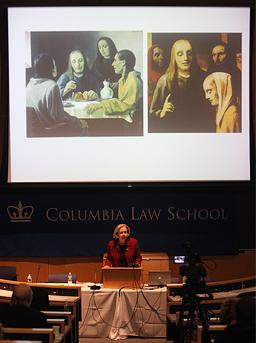

This surprisingly complex question was analyzed at a symposium held recently by Columbia Law School’s Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts. Amid a backdrop of notorious multimillion dollar art world controversies, legal scholars, attorneys, insurance underwriters, art curators, and others gathered last month to share their insights and discuss practical considerations in weighing questions of authenticity.

One of the first struggles in attempting to establish authenticity, said keynote speaker Patty Gerstenblith, Distinguished Research Professor of Law at DePaul University College of Law, is confronting what she calls the Van Meegeren Problem – “If the disputed work is such a good forgery, what’s the harm?”

Han van Meegeren, one of the most infamous figures in the 20th century art world, specialized in forging paintings by the Dutch master Johannes Vemeer. Although he was eventually convicted, in later years many people held up van Meegeren and others to be sentimental and heroic figures, Robin Hoods who had perpetrated victimless crimes and rejected elitist notions of originality in art.

Gerstenblith believes that art has a purpose, to help preserve a cultural and historical understanding of ourselves. To do that, she said, “We need true and authentic representation.”

The search for authenticity frequently faces challenges related to attribution, significance, and provenance. For one, artists are often viewed as sole creators, producing original work – or as copyright practitioners see it, “non-obvious” material. But that conception often ignores the collaborative process of creation, from cave painters to Andy Warhol’s factory. Moreover, artists have “moral rights” and are often given the authority to disclaim authorship of a work.

When disputes wind up in court, judges must examine issues that are almost philosophical in nature.

For example, in one case, Levin v. Gallery 63, purchasers sued an art gallery for selling a 19th century European sculpture as an “original” work by a famed sculptor rather than a copy made by his workshop apprentices. At the time of creation, it may have been perfectly understood that masters could direct staff to execute ideas without giving up authorship. However, today’s art buyers may not be comfortable with such a once-accepted common practice.

Patty Gerstenblith, Distinguished Research Professor of Law at DePaul University College of Law

“Should the law protect economic value or cultural value?” Gerstenblith asked. “I aim to present the idea that both need to be equally protected.”

The Oct. 28 event’s other keynote speaker, John Cahill, a partner at Lynn & Cahill LLP, acknowledged that art scholars have a role in determining cultural significance, and these opinions often convey value and inform legal judgment, but ultimately, disputes get resolved by an adjudication of what’s expected by a buyer and seller in a market transaction.

As a litigator who has been involved in numerous art market disputes, Cahill noted that disputes over authenticity often turn on explicit sales warranties, the uniform commercial code, and an appreciation of what a “reasonable person” might have expected when reading an art seller’s marketing material. A lack of mutual understanding between those selling and buying artwork opens the possibility of future controversy when appreciation of authenticity shifts with cultural changes. Thus, he advises specificity when someone wishes to sell art.

Cahill (left) believes that the market is the best place to determine issues of authenticity because real understanding about art can take a long time to change, and experts are afraid to speak up without fear of liability. As one example, the lawyer pointed to the Andy Warhol Foundation, which recently disbanded its authentication committee after spending an estimated $7 million defending lawsuits.“Nobody wants to be sued,” he says. “So they might say, ‘We might not feel comfortable saying this is authentic.’ The real experts will say in confidence, ‘This is absolutely fake but I can’t say that.’”

Gerstenblith noted that the market is always trying to adapt its understanding of art based on the informed opinion of experts. Cahill stated that the market may be “expert-driven,” but lacks consensus in many cases.

All parties seemed to agree that the legal process will play a prominent role in resolving some of the swirling controversies haunting the art market. With billions of dollars changing hands, and scholars struggling to identify the cultural underpinnings of true authorship and real creativity, many hope that a legal understanding can help soothe growing anxieties over the real value of art.

“In putting together this symposium, our goal was to highlight the complicated legal issues that surround art authentication and look at how attorneys, foundations, scientists, historians and connoisseurs view the process," explained Philippa Loengard ’03, assistant director and lecturer-in-law, Kernochan Center. “Certainly the news that the Warhol Foundation would stop authenticating the artist’s works set the stage for a very timely discussion. It was wonderful to have so many leaders in the field on our panels and in our audience. While it is impossible, of course, to find answers to these problems in a day, I think the excellent discussion put a spotlight on the important questions and brought out potential solutions to some of the most complex issues.”

For 30 years, the Kernochan Center has been fulfilling its mission to advance the understanding of the legal aspects of creative works of authorship.

# # #

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, stands at the forefront of legal education and of the law in a global society. Columbia Law School joins traditional strengths in international and comparative law, constitutional law, administrative law, business law, and human rights law with pioneering work in the areas of intellectual property, digital technology, sexuality and gender, criminal, and environmental law.

Visit us: www.law.columbia.edu/

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/columbialaw