In Qualified Praise of the Immigration Act of 1965

New York, December 21, 2015—When U.S. President Lyndon Johnson signed the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, he downplayed the significance of the new law, predicting it would “not affect the lives of millions.” Yet 50 years later, the act should be regarded as one of the most important laws of the civil rights era, according to a new book,The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act: Legislating a New America, co-edited by Rose Cuison Villazor LL.M. ’06, a visiting professor at Columbia Law School.

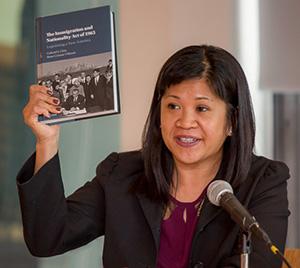

| Visiting Professor Rose Cuison Villazor LL.M. '06 is the author of The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act: Legislating a New America. |

“The Immigration Act was instrumental in the creation of a more racially and ethnically diverse nation,” said Villazor, a professor and research scholar at the University of California, Davis, School of Law, who edited the new book with fellow UC-Davis Professor Gabriel J. Chin. Before the 1965 Act, U.S. immigration law had long expressed preferences for white immigrants, with country-of-origin quotas that heavily favored Northern Europeans. “The 1965 Act was the first immigration statute that prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, sex, place of birth, or place of residence.”

To celebrate the book’s release, Columbia Law School’s Center for the Study of Law and Culture hosted a panel discussion on the legacy of the Immigration Act, moderated by the center’s director, Professor Kendall Thomas, far right. The panelists included, from left to right, author Rose Cuison Villazor, Fordham Law School Professor Joseph Landau, and Columbia University History Professor Mae Ngai. |