Paying (for) Attention

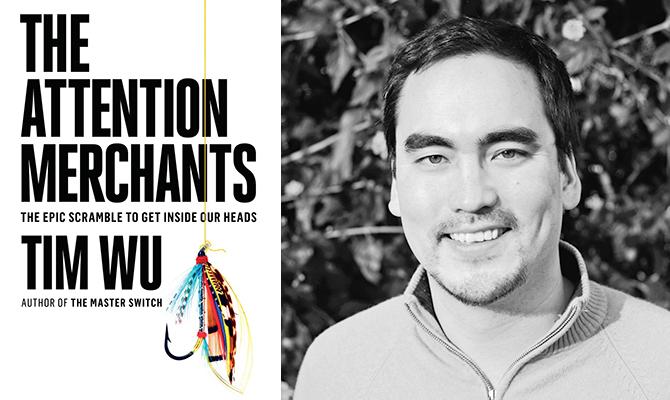

Photo: Mikiko Hayashi

Facing a constant barrage of sophisticated ads, targeted branding efforts, customized social media content, and clever commercials, our society is more distracted than ever, believes Columbia Law School Professor Tim Wu, who writes about the advertising industry’s role in today’s media-inundated world in his new book, The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads.

The tech policy and media law expert, best known for coining the term “net neutrality” and for his earlier book, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, built the 432-page treatise around the premise that attention itself has become the currency of today’s digital world, and the “last scarce resource.”

The book, published by Knopf, has already been profiled in Publishers Weekly and received glowing reviews from The New York Review of Books and Booklist. “Wu…explores in surprising detail the history of those ‘attention merchants’ among us who have ingeniously drawn our notice, then packaged it for financial and political gain,” wrote Alan Morris in Booklist. “The end result is a serious and timely study… that will add depth to an ongoing, urgently needed national and global conversation.”

Yesterday, Wu discussed The Attention Merchants with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air.

In addition to serving on the Columbia Law faculty, where he teaches courses on antitrust and trade regulation, copyright law, criminal law, and the media industries, Wu directs the Poliak Center for the Study of First Amendment Issues at Columbia Journalism School. In 2015, he was appointed to the Executive Staff of the Office of New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman as a senior enforcement counsel and special advisor. In 2011 and 2012, Wu served as senior advisor to the Federal Trade Commission.

Before kicking off a nationwide book tour this week, Wu answered a few questions:

1. What is an attention merchant?

An attention merchant is anyone whose business is attracting human attention to resell for profit. The category is broad and includes ad-based TV channels, celebrities, social media sites like Facebook and Instagram, and so on. Basically, it is business of gathering a crowd by creating something so alluring, sensational, or even useful that you can’t help but pay attention—and the crowd itself can then be sold to advertisers.

The attention merchants drive what the book calls the “attention harvest,” namely, a process of gathering as much human attention as possible to sell to the advertising industry. This book is mainly the 100+ year-long story of the attention harvest. Once small and obscure, it has grown to become a major part of our lives.

Today, on average, Americans spend about 3 hours with their phone, nearly 5 hours with television, and some other hours with their computers. Throw in some sleep, and that’s basically our lives. So policing the bargains is really important

2. What inspired you to write about attention merchants?

So you might have noticed that every day you are typically faced with hundreds—if not thousands— of efforts by companies vying for your time and attention, whether on the web, television, your phone, billboards, you name it. This may the greatest moment-to-moment difference between our lives and those of people 100 years ago. We’ve become used to it, but I think it tends to make us all a bit crazy.

I wanted to understand—just how did this happen? Where did it become the norm that so much of our life is subject to the “attention harvest?” We agreed to all of this—sort of—but is it possible we are living lives that aren’t quite ours? These were some of the questions I was interested in.

At a personal level, I guess, I just wanted to understand time and attention a little better (Jorge Borges once said, late in life, that the one thing he found the most mysterious was time). Why does a day in the desert sometimes seem to last a week? How is it that you can sit down to write an email, click on a random link, and suddenly two hours disappear?

So I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about attention over the last four years (you might say, paying attention to attention), and I’m convinced that as everything else becomes more abundant (food, entertainment, etc.) our attention really will be the last scarce resource.

3. What was the most surprising thing you learned while writing this book?

First, that the origins of the advertising industry are actually even darker than I had thought. The marketing of orange juice as a kind of patent medicine for babies was one thing that struck me. Another was that I knew tobacco had a dark history, but the early campaigns to get women to smoke by selling cigarettes as a way to lose weight were pretty intense.

Second, I was alarmed by how effective the totalitarian and propaganda regimes of the 20th century were at what we now call “advertising.”

Can I have one more? I was surprised to see just how effectively the countercultural ideas of the 1960s became a selling tool—I guess Mad Men was right about that.

4. How has the job of the attention merchant changed over the last decade?

Two ways. First, the so-called competition for eyeballs has just gotten more competitive in just about every way. And unfortunately, the race is usually to the bottom: the more lurid and attention-getting stuff tends to win out, at least in the battle for short-term attention. That helps explain why once “respectable” shows like Nightline have become tabloid shows of the 90s, and why even major print outlets borrow techniques from BuzzFeed.

There has also been a major change in how much of our lives are subject to commercial harvest. There was once something of a line between our private lives—family and friends—and time spent with the entertainment industries. Social media, in particular, has blown that line apart, so that you socialize but in a manner that keeps you available to be reached by advertising. Nowadays, if you hang out with

your friends in-person at a quiet cafe, you’re basically stealing from the attention industries.

Yet while all this is going on, there are also signs of revolt. Many young people—and some older ones too—are determined ad-avoiders and ad-blockers. Parents are concerned about “screen time” and many people now pay for stuff on Netflix or Amazon, as opposed to just channel surfing. Overall, I’d say it’s a tough time to be in the attention business.

5. Oprah, Instagram celebrities…Donald Trump? Who is the ultimate attention merchant? Why?

Surprised you didn’t mention Kim Kardashian--though if history is any guide her career may be hard to sustain (anyone remember Paris Hilton? How about Cornelia Guest?). So since this book ranges across history, it’s only fair to admit that, over the 20th century, the most successful figure at attention capture was Adolf Hitler and his propaganda ministry. The Third Reich created a version of “primetime” that you were legally required to listen to, and of course also banned any competition. By using the advanced technologies of the day, as one of his advisors put it,“80 million people were deprived of independent thought … [and] subject to the will of one man.”

I’d also give great due credit to the CBS and NBC networks at their height in the 1950s, when the two networks had an audience of roughly 100 million viewers each and every night of the week (during a time when the US population was smaller). Those broadcasters had audiences that were completely unbelievable, and today are only equaled during the Super Bowl.

But speaking of our times, I do have to give Mr. Trump credit. He may not be able to force you to listen to him like the totalitarians did, but still he has made it virtually impossible to avoid him. The year 2016 has reminded me of living in Maoist China: one man’s face is everywhere. Trump does not have KNOPF Q&A the advantage of state-controlled media, but he has had a private media so desperate for attention and ratings that they are willing to cover his story endlessly.

6. Is there anything we can or should be doing to stop attention merchants?

They have very dark moments, but my book doesn’t view the attention merchants or advertisers as evil. The fact is—and maybe I should have said this earlier—that our dealings with the industry are consensual, or at least somewhat consensual. It usually works like this: we get free stuff, and in exchange we watch ads. Sometimes it’s even a good deal. Other times, it’s terrible.

What I really think we need to do is be more vigilant about policing the bargain, and make sure we don’t trade away our attention for nothing or too little. Thinking about how many hours you spend with your computer TV and cell phone can make it clear how much is at stake.

7. What do you want readers to take away from The Attention Merchants?

Three things. First, I want readers to have a visceral sense that their attention really is both scarce and incredibly valuable, and so getting some sense of how they actually spend it is really important for contemporary living.

Second, to understand that the attention industries are powerful and something one must be careful dealing with. I’ve already discussed the individual part. At the social level, we need to understand that like all industries, they tend to grow without natural limit. And if we’re not careful, they can overgrow parts of our society, economy, and lives, even if we may not want them to. Just look what has happened to politics, religion, and so many other fields that are now dominated by attentional contests.

Third, I hope they’ll understand that when things get too bad, it is worthwhile and important to revolt, by blocking ads, cutting cords, reading books and so on. Americans can be at times surprisingly passive, and then at other times surprisingly rebellious. As this book shows, the rebellions make a big difference, and I hope we don’t lose that spirit.

# # #

Posted October 18, 2016