Michael Heller's Gridlock Economy

PROF. MICHAEL HELLER’S NEW BOOK “THE GRIDLOCK ECONOMY”

REVEALS A FREE MARKET PARADOX

There Can Be Too Much Ownership

REVEALS A FREE MARKET PARADOX

There Can Be Too Much Ownership

Press contact: Erin St. John Kelly [email protected]

Office 212-854-1787/Cell 646-284-8549/Public Affairs Office 212-854-2650

October 1, 2008 (NEW YORK) – Every so often an idea comes along that transforms our understanding of how the world works. Columbia Law School Professor Michael Heller has discovered a market dynamic that no one knew existed. In his new book The Gridlock Economy: How Too Much Ownership Wrecks Markets, Stops Innovation, and Costs Lives, Heller reveals a free market paradox: usually, private ownership creates wealth, but too much ownership has the opposite effect – it creates gridlock. When too many people own pieces of one thing, cooperation breaks down, wealth disappears and everybody loses.

Gridlock is all around us. “25 new runways would eliminate most air travel delays in America. So why can’t we build them?” asks Heller. “50 patent owners are blocking a major drugmaker from creating a cancer cure. Why won’t they get out of the way? 90% of our broadcast spectrum sits idle while American cell phone service lags far behind Japan’s and Korea’s. Why are we wasting our airwaves? And 98% of American American-owned farms have been sold off over the last century. Why can’t we stop the loss?”

These puzzles sparked Heller to write the book. “I realized that all these problems are really the same problem – one whose solution would jump-start innovation, unleash trillions of dollars in productivity, and help revive our slumping economy,” he said. “The Gridlock Economy is intended for an audience of problem-solvers. It’s aimed at entrepreneurs, citizen activists, policy makers, and law students – anyone interested in the hidden workings of everyday reality and in assembling resources for positive change.”

In his earlier research, Heller, the Lawrence A. Wien Professor of Real Estate Law, has explored ownership puzzles in a wide range of settings. “For me, legal theory comes out of concrete experiences, things I can touch and see. It’s why I love teaching property law,” he said. In “Land Assembly Districts,” (Harvard Law Review, with Rick Hills), Heller proposes a simple, workable solution to the problem of eminent domain abuse. His Corporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy Reforms (Princeton University Press, 2006, co-edited with Columbia Law School Professor Merritt Fox), reflects on post-socialist economic experience to illuminate the fundamentals of corporate governance. In “The Liberal Commons,” (Yale Law Journal, with Hanoch Dagan), Heller explores declining black landownership in America and offers a new theory of commons property.

Heller’s work on “The Tragedy of the Anticommons,” published in the Harvard Law Review and in Science, draws on post-socialist transition and biomedical research to show how the creation of too many private property rights can be as costly as creating too few. Working in Russia for the World Bank from 1990-94, Heller saw that the government split ownership of storefronts among too many parties, any one of which could block use, and did. One new owner was given the right to sell a store; a second, the right to lease the same store; a third, the right to occupy it. Heller writes in The Gridlock Economy, “Looking into those empty stores was my first glimpse, quite literally, of a gridlock economy.”

“Today, the leading edge of wealth creation requires assembly. From drugs to telecom, software to semiconductors, anything high tech demands the assembly of innumerable patents,” Heller writes. “And it’s not just high tech that’s changed – today, cutting edge art and music are about mashing up and remixing many separately owned bits of culture. Even with land, the most socially important projects, like new runways, require assembling multiple gridlocked parcels. Innovation has moved on, but we are stuck with old-style ownership that’s easy to fragment and hard to put together.”

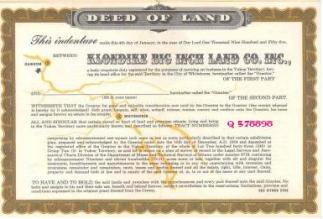

Even in writing the book, Heller faced gridlock: he couldn’t assemble rights to images he wanted to use. Sometimes he couldn’t find counterparts to bargain with, other times people emerged asking for payment based on long-shot claims. To reproduce his Quaker Oats “Big Inch” deed, a central metaphor for gridlock, Heller negotiated a “no objection letter” from PepsiCo because no one was sure who owned the rights.

Heller uses his Big Inch deed to show how gridlock can arise. In the late 1950s, Quaker Oats subdivided about 20 acres in the Klondike into about 21 million square inch parcels and put the deeds into cereal boxes. Imagine one inch pieces of land with tooth picks as fence posts. “If oil were found beneath the inches,” Heller says, “then putting the land back to productive use might have been quite a bargaining challenge.”

In the book, Heller offers a lively tour of gridlock battlegrounds, from medieval robber barons to modern day broadcast spectrum squatters, from Mississippi courts selling African American family farms to troubling New York City land confiscations, and from Chesapeake Bay oyster pirates to today’s gene patent and music mashup outlaws. With some simple policy tweaks and innovative business practices, Heller shows, many gridlock dilemmas could be solved. “Nothing is inevitable about gridlock,” he said at an Authors@Google talk. “It results from choices we make about how to control the resources we value most. We can unlock the grid once we know where to start.”

Reviewers agree. Larry Lessig writes, “Heller’s clear and beautifully crafted analysis is absolutely compelling, and will fundamentally change the debate in core policy areas. There are very few books that reorient a field. Almost none that reorient many fields. This is in that ‘almost none’ category.” In Slate, Columbia Law School Professor Tim Wu writes, “Heller has managed to pull off one of the most perceptive popular books on property since Das Kapital.” Writing in The New Yorker, James Surowiecki says, “The more we divide common resources like science and culture into small, fenced-off lots, Heller shows, the more difficult we make it for people to do business and to build something new. Innovation, investment, and growth end up being stifled.”

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, stands at the forefront of legal education and of the law in a global society. Columbia Law School joins traditional strengths in international and comparative law, constitutional law, administrative law, business law and human rights law with pioneering work in the areas of intellectual property, digital technology, sexuality and gender, and criminal law.