Law School History, Preserved In a Desk

COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL’S HISTORY, PRESERVED IN A DESK

From TR’s Notebooks to H.F. Stone’s Table, Law Library Holds Artifacts of 150 Years

By JAMES M. O’NEILL

An imposing oak desk occupies the far corner of Kent McKeever’s office, in Room 529 of Columbia Law School’s Jerome Greene Hall. It is different from the standard-issue desks in the other offices in Greene: it is far older, and it has a documented pedigree.

When McKeever inherited the desk in 1994 from Prof. Jim Hoover, his predecessor as director of the Columbia Law Library, Hoover also passed along a letter on Columbia Law School stationery, dated from 1975, which had been banged out on an old typewriter. The note, written by Prof. Arthur Schiller to Prof. Louis Lusky, traces the origins of the desk back to Edmund Munroe Smith, who first taught at Columbia Law School in 1882.

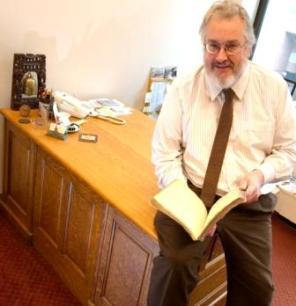

(Photo credit: David Wentworth)

Kent McKeever, director of the Law Library, sits on the edge of the old desk in the corner of his office. The desk has been passed down by generations of Columbia Law School professors.

The desk is one of the few large artifacts that remain of Columbia Law School’s early history, and if not for a few alert professors over the years, even this object could have ended up in a landfill.

McKeever has turned his office into a miniature archive of Law School history, with old chairs, tables and barrister’s bookcases.

He has also rescued other artifacts of the schools first 150 years. McKeever recently purchased a silver tray engraved with the signatures of the Law School’s entire faculty from 1952. The tray had been given to Young B. Smith upon his retirement after 24 years as dean. McKeever has also purchased notebooks of former Law School students, and recently secured copies of a Law School exam from 1908.

“I like history and I don’t want it to be lost,” said McKeever, who first joined the law library’s staff in 1982.

A silver tray given as a gift to departing Dean Young B. Smith includes engraved signatures of the entire faculty in 1952.

“The Law School as an institution has a central purpose, which is research and teaching. Its own history is not critical to its ongoing purpose,” McKeever said. “And institutions just tend to shed their history. But I like saving these items because I view them as grace notes to what the school is doing.”

Whitney Bagnall, who recently retired after 25 years as the Law School Special Collections Librarian, said that each time the Law School moved locations, “things just got thrown out because there was never enough space to store things of historic value.”

A few treasured items have survived. Besides McKeever’s storied desk, a wood table stands in the lobby of the Law Library, which was used by Harlan Fiske Stone when he was the Law School’s dean, from 1910 to 1924.

(Photo credit: David Wentworth)

The large table Harlan Fiske Stone used as a desk when he was dean of the Law School in the early 1900s stands in the Law Library lobby.

In addition, the Law Library stores the seven volumes of notebooks penned by Theodore Roosevelt when he was a student at the Law School in 1881.

On first glance, Roosevelt’s notes appear amazingly neat to the modern eye – not the messy sort of class notes quickly scratched out in the midst of a lecture, or even the shorthand that today’s students might tap out on their laptop computers. McKeever has an explanation.

“It seems students would take their classroom notes and as a form of study would transcribe them in a clearer hand,” he said.

(Photo credit: David Wentworth)

Theodore Roosevelt's student notebooks from his days at Columbia Law School in 1881 are preserved in the Law Library.

Old student notebooks are useful to save because they are a record of what was taught, and how the material was emphasized. “We’re definitely interested in saving old notebooks because at some point someone will come along and want to learn how a particular subject was taught,” McKeever said. “For example, some time ago we had an inquiry about when a particular concept in administrative law first showed up in the classroom, before or after it had it appeared in the case law. The student textbooks from the 1940s and 1950s were the sources consulted.”

The Law Library has saved the notebooks of a number of students from the late 1800s and early 1900s, including those of John Armstrong Chaloner from 1883, which contain notes from lectures on real property law by Theodore W. Dwight, the Law School’s first Warden, or Dean. These share space with the notebooks of Maurice Thompson Moore, a student from 1916 to 1919, who went on to become a partner of the law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Moore was also a director of the Studebaker Packard Corporation.

In the same vein, McKeever recently purchased on eBay for $50 several old Law School exams in torts, equity and contracts, dating to 1908. The concepts tested have not changed much in a century, but the examples used sure have. On the contracts exam, one question asks, “A ordered a carriage manufactured by B, to cost $1,000, examined it when nearly finished, and ordered a few changes which were made. B finished the carriage and notified A that it was ready. B heard northing from A for a week and then sold the carriage to C for $700. What are the rights and liabilities of A and B respectively?”

(Photo credit: David Wentworth)

Decorative detail on the table Harlan

Fiske Stone used when he was Columbia

Law School dean in the early 1900s.

Bagnall said the Law Library has also tried to save copies of all old course catalogs, alumni newsletters and student yearbooks.

Then there’s McKeever’s old oak desk. The desk, which measures 60 inches long and 35 inches deep, was dipped and refurbished in 2000 by Anthony Pallone, director of building services. Each drawer has wood pulls.

In his 1975 letter to Lusky, Schiller begins, “The first occupant of the magnificent oak desk which has recently come into your possession was Edmund Munroe Smith, Bryce Professor of Roman Law and Comparative Jurisprudence.”

In the letter, Schiller wrote that Munroe Smith, a Columbia Law graduate of 1877, joined the faculty in 1882, just before it relocated to a new site on 49th Street in mid-town Manhattan.

Munroe Smith was “the ideal scholar, thoughtful, clear-headed, industrious, patient and dispassionate,” wrote friend Claude M. Fuess, whose recollections were reprinted in the 1955 history of the Law School. Fuess said that Munroe Smith, “especially among his friends, was a fascinating talker. Perhaps he was at his best in the give and take of conversation after dinner or at his favorite club….His ‘That reminds me!’ was invariably the preliminary to an entertaining anecdote or a sparkling epigram.”

Exactly when Munroe Smith obtained the oak desk remains unknown, Schiller writes in his letter, but it moved to Kent Hall, which the Law School first occupied in 1910, after being housed for 13 years in Low Library.

Munroe Smith occupied Room 613 of Kent Hall until his retirement in the early 1920s. Hessel Yntema was chosen to pick up the Roman law course that Munroe Smith had taught, and Yntema hired Schiller, a graduate student, in 1926 to help prepare materials.

During the summer of 1928, amid an academic upheaval within the Law School that Schiller called “the revolution,” Yntema left, and Dean Smith asked Schiller to teach Roman law.

“My remuneration was Room 613 Kent Hall and the desk, with a very small sum in cash,” Schiller wrote. Two years later he was named to the faculty, and continued to occupy Room 613, and use the desk, until the Law School abandoned Kent Hall for its new building in Jerome Greene Hall, across Amsterdam Avenue, when Greene opened in 1960.

“At that moment the fate of the desk was in doubt,” Schiller wrote. “Dean [William C.] Warren was adamant – for a while at least – that all the desks in the new building should be uniform and modern.”

But at least one other professor insisted on moving his old desk from Kent Hall. As a result, Warren apparently relented, and let Schiller move the oak desk to his new office in Greene Hall. Another hurdle now threatened the desk. “The oak desk was too large to pass through the door of the room which I had chosen,” Schiller wrote.

This he solved by taking the desk apart. He had it varnished and refinished, and then reassembled in his new office. He used it for another 14 years, until turning it over to Louis Lusky in 1974.

Lusky was a 1937 Columbia Law School graduate, and then clerked for former Law School Dean Harlan Fisk Stone, who by then was a U.S. Supreme Court justice. As a Columbia Law School professor, Lusky became known as a pioneer in the field of civil rights law and constitutional law, and wrote several books on the U.S. Supreme Court.

When Lusky retired in the early 1990s, the oak desk was again in danger of being discarded. This time Jim Hoover, the Law Library director, rescued it. When he moved on to an associate dean’s position in 1994, he passed it on to McKeever, along with Schiller’s letter of desk pedigree.

And when McKeever one day retires? “Well, I’m sure there will be somebody for whom this echo of the Law School’s past will resound,” he said.