Judge Posner on the Economic Crisis

FINANCIAL CRISIS: A BUSINESS FAILURE TO A GOVERNMENT FAILURE

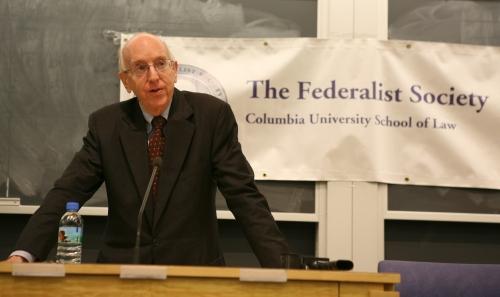

Judge Richard Posner Lectures at Columbia Law School

Judge Richard Posner Lectures at Columbia Law School

Press contact: Erin St. John Kelly [email protected]

Office 212-854-1787 Cell: 646-646-284-8549 Public Affairs 212-854-2650

November 26, 2008 (NEW YORK) – As a staunch proponent of free trade and minimal regulation, U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner told a packed audience at Columbia Law School that he surprised even himself by placing the blame for the current financial crises not with Washington but with the free-market system.

“It’s a painful acknowledgment,” Posner told the crowd, which filled Room 101 of Jerome Greene Hall well beyond capacity.

The 69-year-old judge spent just over an hour addressing the question of whether the “current depression” – a term he adamantly uses – represents a “failure of capitalism” or rather a “failure of government.” He gave his lecture, “Financial Crisis: A Business Failure to a Government Failure,” on November 24.

With hindsight, the reasons for the failure are obvious, Posner said. Excessive deregulation enabled excessive risk-taking. Add to that mix the abundant credit made possible by the Federal Reserve’s loosening of purse strings following 9/11 and the abundant capital of the oil-boom years, and the world faced an economic house of cards of historic proportions.

Indeed, the causes are so obvious now, Posner said, that it is a surprise that hardly anyone saw it coming. “This was a big embarrassment to the economics profession,” Posner said. “Mortgage brokers, local banks and homeowners knew what was going on, but banking and securities regulators did not.”

Posner devoted the bulk of his presentation to outlining the myriad motivations behind the excessive risks. What disturbs him most, he said, is that all of the risk-takers – from CEOs to the day traders to home buyers – were behaving rationally, which free-marketers such as Posner generally believe should act as a bulwark to protect against such catastrophes.

The bankers, for example, were rational in betting on mortgage-backed securities and other housing-related investments, even long after they recognized that their entire industry was, in fact, standing deeply inside an enormous, overstretched bubble. “Even if you know you’re in a bubble, it’s extremely difficult to get out,” said Posner. Pulling up stakes before the bubble explodes means telling investors to expect smaller short-terms rewards. “I think that is a very hard sell,” he said.

Besides, Posner added, when investors want to balance their portfolios, they will do it themselves with, say, bonds or treasuries. The purpose of the high-risk funds is to take the high risks necessary to generate the outsized profits.

Posner also cited the win-win structure of most top executives’ contracts: If their high-risk decisions result in big gains they receive huge bonuses, and if the gambles fail they result in huge severance packages. He noted the $161.5 million awarded last year to outgoing Merrill Lynch chief Stanley O’Neil. “Very, very generous compensation incentivizes executives to maximize their short-term profits,” he added.

Boards of directors, Posner lamented, are hardly “reliable agents of shareholders.” With compensation in the high six-figures for positions that require them to attend only a few meetings per year, board members would need to act against their own self-interest to contest a CEO’s plus-size salary – which wouldn’t exactly be rational.

“This is rational behavior. This is troublesome for economists,” Posner said. “You can have rationality and you can have competition, and you can still have disasters.”

Though he said he wanted to end the presentation on a high note, Posner seemed to have trouble finding one. He could cite no immediate solutions to prevent such collapses from recurring. Merely reintroducing regulations that would have prevented the present fall wouldn’t necessarily forestall the next one, he said, which will be the product of new and different dangers in a new and different industry. “There’s no point in closing the barn doors now,” he said. “I don’t think we have to worry about banks making risky loans for many, many years.”

Posner did, however, offer one bit of advice for his fellow University of Chicago lecturer, President-Elect Barack Obama. Drawing a parallel to the development of the Central Intelligence Agency following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Posner advocated the creation of a “financial intelligence agency” charged with coordinating information about economic problems.

And the judge did find a slight glimmer of hope, if only for a small percentage of the future lawyers in the crowd, in certain job prospects. “It’s a great time to be a financial lawyer,” Posner said. “There will be very interesting cases as courts try to unravel corporate responsibilities, CEO responsibilities, excessive compensation.”

Olga Kaplan ’09, the President of the Federalist Society, which sponsored the presentation, called the turnout “amazing.”

“The subject matter was certainly very relevant,” Kaplan said. “I think it was particularly interesting how Judge Posner tied in so many different facets together to bring a cohesive picture of the economic crisis.”

William Han ’09 one of the dozens of students standing in the aisle for the entire 75-minute presentation, added, “He invented the law-economics field. He’s a rock star among lawyers.”

—Mark Fass

Columbia Law School, founded in 1858, stands at the forefront of legal education and of the law in a global society. Columbia Law School joins traditional strengths in international and comparative law, constitutional law, administrative law, business law and human rights law with pioneering work in the areas of intellectual property, digital technology, sexuality and gender, and criminal law.