Holding Power to Account, Then and Now

“Watergate Girl” Jill Wine-Banks ’68 sees parallels between the pursuit of truth under Richard Nixon and Donald Trump.

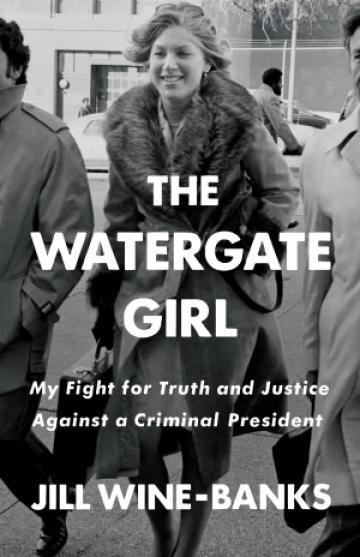

Jill Wine-Banks ’68, currently a legal analyst for MSNBC, began her legal career as a federal organized crime prosecutor. In 1973, she went to work for the Watergate special prosecution team alongside Richard Ben-Veniste ’67, Philip Lacovara ’66, and Charles C.F. “Chuck” Ruff ’63. They won convictions against four members of President Richard Nixon’s administration for their part in covering up the Watergate burglary. In her new memoir, The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President (Henry Holt & Co.), Wine-Banks recounts the intensity of the grand jury investigation and trial, the blockbuster revelation of Richard Nixon’s Oval Office tapes, and her experience as the sole woman on the prosecution team. She shared her insights into presidential indictments, speaking truth to power, and how Watergate changed her life.

Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski believed presidents should not be subject to indictment and would not consider indicting President Nixon. Today, the Justice Department’s legal guidance says the same, and so special prosecutor Robert Mueller didn’t consider indicting President Trump. Do you think a president can be indicted?

I do. I don’t see anything in the Constitution or in any laws that bars it. The argument that Leon was making was not that indictment was against the law or the Constitution, but that it would interfere with the president governing and that because we had a legitimate bipartisan Congressional investigation, we should use it. He argued that the president’s conduct was a political problem that should have a political solution—which is impeachment.

I respect and understand that point of view, but I still think if President Clinton could have a civil trial while he was president, why couldn’t he have had a criminal trial? I don’t see the likelihood of prosecutors bringing a politically motivated criminal case or of grand juries agreeing to indict someone where there is no evidence. There was something unjust to me about trying the people who conspired with Nixon, and sending them all to jail, and not trying the ringleader.

When President Trump overrode the sentencing recommendation for Roger Stone, four federal prosecutors on the case resigned. You were working for special prosecutor Archibald Cox when President Nixon ordered him to be fired in October 1973. Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy William Ruckelshaus quit rather than do so. Did you also consider resigning in protest?

We had that exact debate after Archie Cox was fired: should we stay or should we resign in protest? We decided we would not resign in protest, that that was a hollow action, and that as long as we could continue having a grand jury investigation, as long as we could continue interviewing witnesses and collecting documents, we should do our job.

The decision of the prosecutors to resign in the Stone case may be the right one. Somehow, people are going to have to start speaking truth to power and standing up to this president. I think Donald Trump and William Barr are so much worse than what we experienced. It's terrifying to me, in part because of what they did and how awful it is, but also because they have such a long history of terrible conduct that we are becoming inured to it. We're numb, and the public is not protesting. [Stone was sentenced on February 20 to 40 months in jail.]

Watergate resulted in federal legislation to regulate campaign finance and in a wave of lawyers choosing public interest careers. Is the Trump impeachment likely to have the same effect?

I think there should be changes to the special prosecutor legislation. It needs to be clear that there’s independence. The fact that, under the current rules, the special prosecutor’s report goes to the attorney general, and then it’s up to him as to what happens to it, is wrong. If you're investigating the president, who appoints the attorney general, then the attorney general has an inherent conflict of interest. If there weren’t a conflict, the regular Department of Justice could be doing the investigation. If you start out with the assumption that you cannot indict the president but are clearly investigating the president, that's a pretty big hurdle.

In 1968, my graduation year, going to the Department of Justice was considered a wonderful thing. I should point out that Wall Street doubled its starting salary for lawyers the year I was graduating because so many of my classmates, including me, wanted to go into public service. Now, if I were thinking about going to a government agency, I think I would look at a state agency. I would not be looking at the federal government, even if I were a Republican—short of being a Trump loyalist. What I’m seeing at the Department of Justice would be disturbing to me and would make me think twice.

Your book talks about the pervasive sexism of the 1970s. During your questioning of Rosemary Woods, Nixon’s secretary, about the 18 ½-minute gap in the Oval Office tapes—a pivotal moment—Judge John J. Sirica embarrassed you in court by saying, “We have enough problems without two ladies getting into an argument.” How much has changed for women in the law today?

You can’t respond to the judge. You cannot yell at the trial judge. You just feel your blood drain from your body completely. You say nothing and then just gather yourself together and go back to working. That incident led to a letter of protest from 300 Columbia Law students, who wrote to Judge Sirica criticizing his behavior. It was the first and only time I had significant support during the Watergate trial. And he did apologize to me after that.

I speak at law schools and at bar associations, and I hear from young new lawyers that they are still encountering sexual harassment and discrimination. Much of the behavior I encountered and the questions I was asked in job interviews—what kind of birth control do you use? Are you planning to have children?—are now illegal. It doesn’t mean that the interviewer isn’t thinking about those issues when they interview you. Now, no one would say those things, but I don't think the attitudes have quite gone away.

How did the Watergate investigation change your life?

I was raised to respect the president and the presidency, regardless of my views of the incumbent’s policies. I remember listening to the first [Nixon] tape. It was a gut punch to hear the president, in the Oval Office, committing crimes. It was devastating. I could never view President Nixon in the same way again.

The situation with President Trump is equally devastating. I never thought I’d live to see someone engage in more criminal conduct in public than Nixon did in secret. Back then, I always knew that it would work out and justice would be done. Right now, the system isn’t working, and that’s scary to me.

In a practical sense, being a Watergate prosecutor opened a lot of doors for me in terms of careers. I became the first woman to be the general counsel of the U.S. Army. That was a phenomenal opportunity and job. I was able to accomplish a great deal in that position that I’m very proud of and to meet some of the best leaders that I've ever met. And because my photo appears in the New York Times during the Watergate investigation, my high school boyfriend and I reconnected–and he is now my husband of 40 years.