A Fighter For All Causes: Flo Kennedy ’51

Long before intersectionality became a watchword, Florynce Kennedy ’51 identified the confluence of race and gender discrimination, bringing to second-wave feminism a Black voice that was impossible not to hear. But first, she took on Columbia Law School.

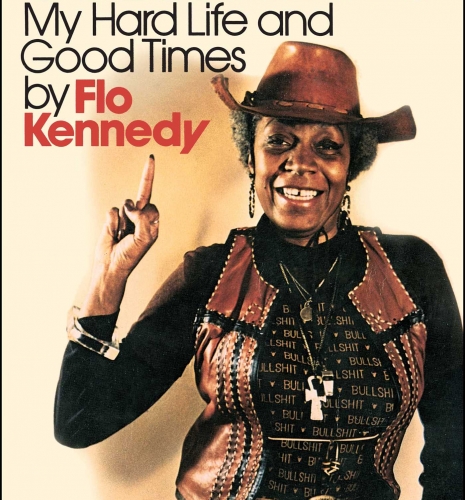

Photo: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Florynce “Flo” Kennedy GS ’48, LAW ’51 spoke out against racial and gender injustice during the protest-filled 1960s and ’70s. She was active in the civil rights and Black Power movements and in the fledgling National Organization for Women (NOW). She took on lightning rod cases, representing clients including the Black Panthers and the woman who shot Andy Warhol. When NOW became too mainstream for her, she founded the Feminist Party to support the presidential run of Rep. Shirley Chisholm in 1972. Like Bella Abzug ’45, Kennedy was fond of hats and almost always was photographed wearing a cowboy hat, sailor cap, or other headgear. She dressed to catch the eye, and she spoke in aphorisms designed to provoke. But her activism led to fundamental change, including New York becoming the first state in the nation to legalize abortion.

Read more about Flo Kennedy’s lifelong activism below.