European Union Tested by Migrant and Russian Crises

Thomas Bagger, Head of Policy Planning for the German Foreign Ministry, Says Germany Must Formulate Responses to Current Challenges Amid Evolving Problems for the European Union's "Community of Law."

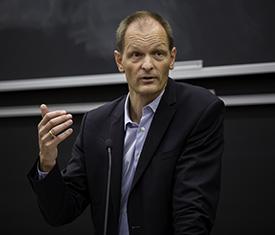

| Thomas Bagger, policy chief for the German Foreign Ministry, says that Europe's migrant crisis is testing the bonds of the European Union. |

New York, October 5, 2015—The migrant crisis in Europe and Russia’s aggression in the Ukraine are testing the bonds of the European Union and the principles of international law, said Thomas Bagger, head of policy planning for the German Foreign Ministry, in a speech Tuesday at Columbia Law School.

Bagger began by noting that Germany will celebrate the 25th anniversary of its reunification this Saturday, October 3. “It is a success story,” he told students, while on a break from meetings of the United Nations General Assembly. He recalled then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl optimistically observing that, for the first time in its history, Germany was “surrounded by friends.”

But now the flood of refugees from the Middle East into Europe and Russia’s military intervention in the Ukraine have “both shattered a pretty powerful self-perception of Germany as an island of tranquility,” said Bagger. “They’re also shattering our convictions that there’s a smooth, almost mechanical path forward for the project of European unification.”

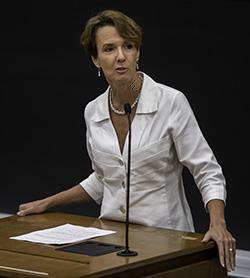

| Professor Sarah H. Cleveland, director of the Human Rights Institute, invited Thomas Bagger to address students, staff, and faculty. |

Bagger joined the German diplomatic service in 1992. Since then, he has been posted at embassies in the United States, Prague, and Turkey. He was the head of the German Foreign Minister’s office before assuming his current position four years ago.

“He is widely recognized as one of the brightest minds in the German Foreign Ministry,” said Professor Sarah H. Cleveland, director of Columbia’s Human Rights Institute. Bagger’s talk was co-sponsored by the Human Rights Institute, the Center on Global Governance, the Society for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, and the Center for European Legal Studies.

A string of troubles have dogged the European Union in recent years. In the aftermath of the global economic crisis and bailouts for governments, questions surrounded the EU’s use of a common currency and Germany’s position as the union’s preeminent power. Bagger said postwar Germany had long tried to pursue policies that avoided foreign interventions: “If we don’t meddle too much in other people’s affairs, we have nothing to fear of anyone.” But then in 2014 Germany had to play a central role in forging a united EU response to Russian military intervention in the Crimea and Ukraine, including the imposition of economic sanctions in cooperation with the United States.

Yet the process of getting all 28 member states on the same page “was not natural,” said Bagger,

because the different countries had different histories with Russia, from those “who suffered through four or more decades of Soviet occupation” to the Western European members who saw Russia as “a distant country with whom they trade.” Before the sanctions expire in January 2016, Bagger anticipates “all kinds of difficult discussions among Europeans about what to do next.”

| After his remarks, Bagger took questions from the standing-room only audience. |

More troubling in the long-term, said Bagger, is Vladimir Putin’s challenge to “our reading of international law.” Though Putin’s speech this week before the United Nations avoided mentioning the U.S. by name, the Russian president complained about the overreaching of others and advocated a return to a more “classic notion of international law based on principles of national sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs,” said Bagger.

Bagger said he believes only international cooperation will solve Europe’s current migrant crisis, the second challenge discussed in his wide-ranging speech. Unlike Russia’s sudden military intervention, he said, the flood of refugees did not come as a complete surprise. “There are more refugees and displaced persons than at any point since World War II, somewhere upward of 60 million people globally,” he explained, noting that in recent years Germany became the second largest immigration destination among the 34 countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

“In 2014, we had about half a million net migration into Germany, in a population of 80 million,” Bagger said. “Most of them came from other EU member states. Last year about 60,000 came from Syria.” This year the number of refugees has gone up dramatically, with 150,000 in September alone and an estimated 800,000 over the course of the entire year.

He pointed out the varied responses from EU countries—both welcoming and antagonistic—to the migrants.

These differences underline a more practical problem, Bagger said: The cohesion of the European Union as “a community of law,” with standard procedures and an equitable distribution of refugees. “It is in many ways a German moment,” Bagger said. “But it needs the European dimension to be sustainable. If we don’t manage a joint EU response, what you will see—what you can see in parts already—is a fragmentation of Europe. Borders will go up again.”