Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates Discusses Federal Prison Reform

Second in Command at Department of Justice Says Sentencing and Rehabilitation Must Be at the Heart of Criminal Justice Reforms

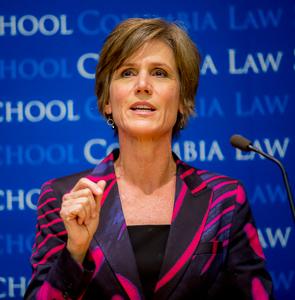

New York, November 4, 2015—One day before the U.S. Department of Justice began to release 6,112 inmates convicted of lower-level drug offenses, U.S. Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates outlined a program of major reforms to the federal prison system, in an Oct. 29 speech at Columbia Law School.

| In a speech at Columbia Law School on Oct. 29, Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates outlined a program of major reforms to the federal prison system. |

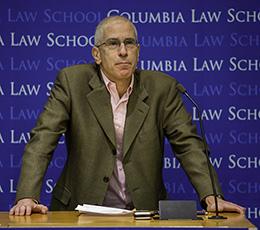

In her speech, "Thoughts on Criminal Justice Reform,” Yates praised both Columbia Law School as “a world leader in legal scholarship and education” and the event’s chief sponsor, The Center for the Advancement of Public Integrity (CAPI), for its “efforts to promote honest, effective government.” Yates was introduced by CAPI Executive Director Jennifer G. Rodgers and Advisory Board Member Daniel C. Richman, the Paul J. Kellner Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, an expert in federal criminal law, criminal procedure, and evidence.

“I’ve spent most of my adult life working in the criminal justice system,” said Yates, a longtime federal prosecutor and a former U.S. Attorney in Atlanta. This year, she was named the Deputy Attorney General, overseeing the day-to-day operations of the Justice Department, which includes not just the nation’s prosecutors but also such agencies as the FBI, DEA, ATF, U.S. Marshals Service and Bureau of Prisons. “I see all sides, and I can tell you confidently the status quo needs to change,” said Yates.

Yates noted she’s not alone in the call for criminal-justice reform, as a bipartisan consensus has been emerging around the issues of sentencing and prisons. The federal prison population has exploded over the last two decades, with a nearly 200 percent increase in the number of offenders serving a mandatory minimum sentence. Maximum sentences for drug offenders were lowered last year by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, and last month Yates testified before Congress in support of a bill that would address proportionality in sentencing, particularly for nonviolent drug offenders.

Yet, while Yates found that many elements of legislation “promising,” she said it’s not enough. “If we are really committed to justice, as a country, we have to be willing to invest in stopping crime before it starts,” said Yates. “We all know that we can’t simply jail our way into safer communities, but until we are willing to invest in preventing crime the same way we are willing to invest in sending people to prison, our communities will not be as safe nor will our system be as just as it should be.”

| Yates was introduced by Jennifer G. Rodgers, left, executive director of the Law School's Center for the Advancement of Public Integrity, (CAPI) and Professor Daniel C. Richman, who serves on the CAPI advisory board |

The ignored key to crime prevention, she said, is rehabilitation, because 40 percent of federal prisoners and two-thirds of state inmates will reoffend within three years. “We have to break that cycle.” Yates discussed two Justice Department projects that she hopes will have a positive impact on crime by providing “more effective paths” for offenders to reenter society.

The first involves inmate literacy, as more than 70 percent of inmates in state and federal prisons can’t read above a fourth-grade level. “Many of the daily tasks that we take for granted, like reading a job application, are much harder if not impossible [for them],” Yates said. “Research shows that improved literacy substantially reduces the likelihood that an inmate will re-offend.” Federal prisons currently help more than 20,000 inmates obtain high-school-equivalency diplomas, but Yates said the G.E.D. can’t be the yardstick to measure future success. “No one should leave the Bureau of Prisons without being able to read.”

The second initiative focuses on building job skills. An existing program, called Federal Prison Industries, trains more than 12,000 inmates to manufacture a variety of products, “from furniture to electronics.” While it’s sometimes dismissed as “prison labor,” Yates said, FPI teaches technical as well as “soft” skills necessary to hold onto a job—“things like being on time, following instructions, and finishing a task.” But now the 80-year-old program is in dire need of an overhaul, said Yates, because the demand for its products and services has dropped “dramatically” and almost 11,000 inmates who want to participate in FPI are on waiting lists. She promised “substantial reforms to retool FPI” to better train inmates to find success when they leave prison.

The timing is urgent, Yates said. Current broad-based support for changes in the criminal-justice system makes this “a unique moment in our history,” she explained, with reforms currently being implemented in 29 “red states and blue states” across the country. “Even Congress—which doesn’t agree on much these days—is on the cusp of significant sentencing reform legislation.”

A former federal prosecutor and U.S. Attorney, Yates told the Columbia Law School audience: "I’ve spent most of my |

Yates cited a couple of these “innovative” reforms. One is a federal drug court in Brooklyn that offers treatment and job opportunities. A second, called “Turning Leaf,” enlists the South Carolina business community to secure jobs for the released. In addition to helping participants find employment, Turning Leaf employs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to get prisoners to “think differently,” or to think before acting. Inmates told Yates about a hand gesture—putting two fingers on their temples—to use whenever they want to “get high” or felt anger.

“It [gives] them an extra moment to reflect on their decision-making,” said Yates. “Three decades ago, when our country was focused just on being ‘tough on crime,’ it was impossible to imagine that we would ever find a way to return proportionality to our sentencing laws. But we are closer than ever, thanks to the sustained efforts of those willing to call out injustices and demand meaningful change. It’s time that we collectively discard old assumptions and embrace new ideas. In other words, it’s time we all collectively put two fingers to our temples.”

The event was co-sponsored by Columbia Law School’s Social Justice Initiatives.